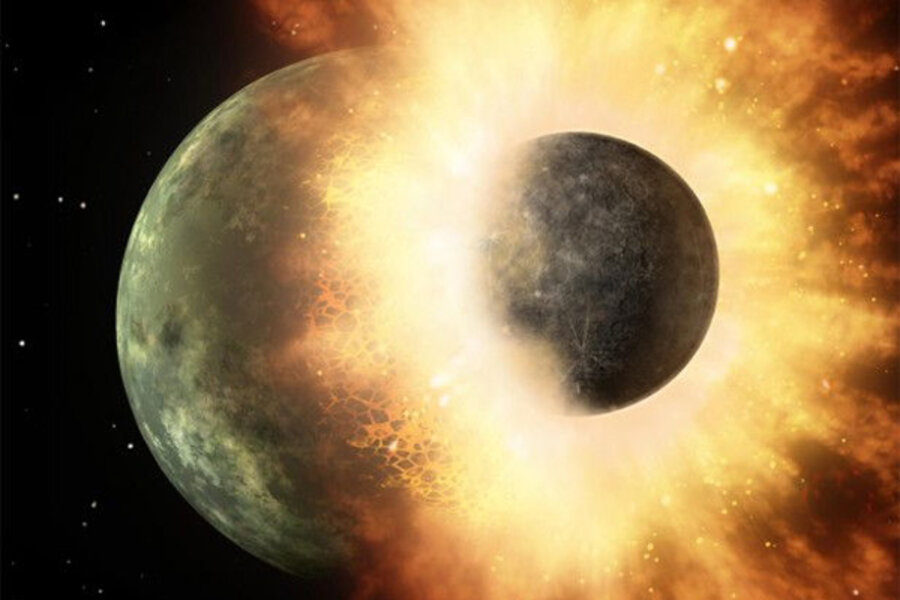

Scientists confident moon born of colossal Earth collision that vaporized Zinc

Loading...

Water on the moon boiled away in massive quantities in a cataclysmic evaporation event during the moon's birth, bolstering the theory that a Mars-sized body collided with the Earth to form its only natural satellite, scientists say.

Researchers examined rocks collected by astronauts during NASA's Apollo lunar landing missions, as well as a meteorite that originated on the moon to make the find. They looked for traces of zinc, and found the ratios of heavy to light isotopes are greater than on Earth, which suggests the moon went through an intense evaporation event early in its formation.

The study is more evidence for the theory that the moon formed from a colossal impact, researchers said.

Early in the moon's formation, the surface was hot enough to vaporize zinc – and a giant impact is one of the few things that would generate that much heat. Another prediction of the theory is that heavier isotopes would be more common, because they would condense at a higher temperature.

"What we found is that the depletion [of lighter isotopes] of Zinc is probably due to evaporation," said study co-author Frédéric Moynier, assistant professor of Earth and planetary sciences at the Washington University in St. Louis. [How the Moon Formed (Video)]

Zinc on the moon

Moynier, study lead author Randal Paniello and James Day of the Scripps Institution of Oceanography, found that the ratio of zinc-66 to zinc-64 in moon rocks is about three to four times greater than either Earth or Mars. On the Earth and Mars respectively, it is 0.25 to 0.27 parts per thousand. On the moon, it was a difference of 1.3 to 1.4 parts per thousand.

Almost all the samples collected from the moon had similar ratios of heavier to light isotopes, even though they came from very different places all over the moon. (One sample came from a meteorite that originated there).

The team also measured the effect in tektites, which are pebble-sized rocks formed by meteor impacts. They found the same thing: The tektites were also depleted in zinc-64 relative to ordinary Earth rocks.

The high temperatures imply the water vaporized. That would also point to a depletion of other volatiles – elements such as hydrogen, chlorine, sulfur, which vaporize at relatively low temperatures.

Searching for moon water

However, several studies show water present in some lunar rocks.

Recent missions like NASA's Lunar Crater Observation and Sensing Satellite revealed evidence of moon water in 2009. India's Chandrayaan-1 found hydroxyl, an oxygen-hydrogen compound that makes water when bonded to another hydrogen atom.

How much water and other volatiles the moon has is a key question for plans of future lunar exploration by astronauts. Advocates of a "wet moon" say that the lunar mantle may have big stores of those chemicals. But other scientists think the volatiles are mostly in the top layers of lunar soil, brought in by impacts and generally dating from after the moon's formation.

"[The results] show that all this water they found on the face of the moon is secondary water," Moynier said.

Water and volatiles are probably from impacts and the solar wind, Moynier said. The studies showing volatiles in the volcanic glass might be showing local areas that are enriched, relative to the rest of the moon, he added.

Denton Ebel, curator of meteorites at the American Museum of Natural History, noted that there is evidence of seismic activity on the moon and evidence of hydrogen-bearing rocks at the moon's interior. Ebel was not involved it he study.

There is also a heat source at the center of the moon. That would point to some volatiles and water being there. But the new research seems to show a moon-spanning mine of water and other volatiles is less likely.

"The dry moon is dead, but the wet moon is not alive," he said.

Ebel noted that the isotope study confirms a prediction of the impact theory of the moon's formation. There are still a lot of questions, though. For example, the moon's composition is broadly similar to the Earth's mantle – as the impact theory predicts. But the Earth's mantle is depleted in potassium, and the moon's should look the same. It doesn't.

The study also shows how important it is to get samples, Ebel said.

Without the Apollo moon rocks and lunar meteorites, gathered mostly from Antarctica, it would be harder to test the impact theory at all, since the evidence comes from direct chemical analysis.

The research is detailed in the Oct. 18 edition of the journal Nature.

Follow SPACE.com on Twitter @Spacedotcom. We're also on Facebook & Google+.