Humans kill nearly 100 million sharks each year, say conservationists

Loading...

| Oslo

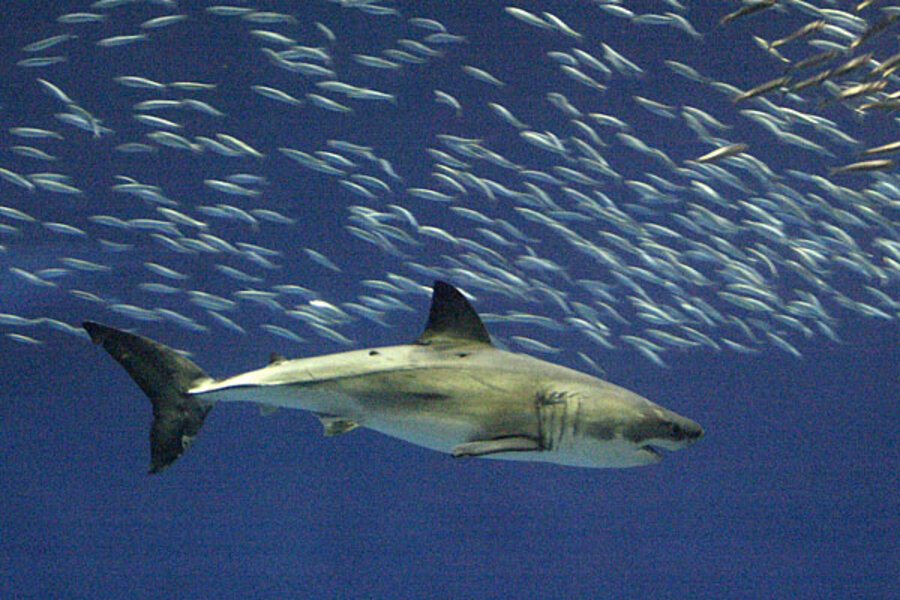

Protection measures have failed to stop around 100 million sharks being fished every year and a third of all shark species are now threatened with extinction, conservationists say.

Many are caught for their fins, a delicacy in Asian soup. The fins are sliced off and the animals are often dumped alive overboard to die of suffocation or eaten by other predators.

Protection for endangered sharks may have lagged because they are relatively unloved compared to animals such as pandas or lions, even though they usually kill fewer than 10 people a year worldwide.

An estimated 97 million sharks, or 1.41 million tonnes, were caught in 2010 compared to 100 million in 2000, according to a study in the journal Marine Policy, the first to estimate the number of sharks killed annually.

"We are now the predators. Humans have mounted an unrelenting assault on sharks and their numbers are crashing throughout the world's oceans," said Elizabeth Wilson, manager of global shark conservation at The Pew Charitable Trusts.

A meeting of 170 nations in Bangkok from March 3 to 14 will consider limits on trade in hammerhead sharks, oceanic whitetip sharks and porbeagle sharks to curb over-fishing. Great white sharks, whale sharks and basking sharks already have protection.

"More has to be done. Some species are really hanging on by a thread," said Boris Worm, a marine biologist at Dalhousie University in Canada, who was lead author of the study with other experts in Canada and the United States.

Demand in Asia for shark fins, a delicacy in soup, is a main driver of catches that also target meat, liver oil and cartilage.

The small fall in catches from 2000 to 2010 may be an encouraging sign of steps to outlaw finning by the United States, Canada, Europe and Australia in the past decade, Worm said. And China plans to phase out shark fin soup in official banquets.

But it may be a sign that sharks are getting harder to find because there are fewer in the oceans, he told Reuters.

Unloved fish

Sharks killed seven people worldwide in unprovoked attacks in 2012, down from 13 in 2011 but above the average for 2001 to 2010 of 4.4, according to the International Shark Attack File compiled by the University of Florida.

On Wednesday, a New Zealand man was attacked and killed by a great white shark.

Friday's study estimated that between 6.4 and 7.9 percent of the world's sharks are caught every year, depleting numbers since sharks grow slowly, have few offspring and numbers can only rebound at about 4.9 percent a year.

Pew urged delegates at the Bangkok meeting of the Convention on International Trade in Endangered Species to agree more protection for sharks and rays.

Worldwide there are about 500 species of shark, ranging from the dwarf shark that can fit in the palm of a hand to the whale shark, the largest fish in the oceans that can grow up to 12 metres (40 feet), the length of a bus.

A third of those species risk being wiped out, according to the International Union for Conservation of Nature.

(Reporting By Alister Doyle; Editing by Tom Pfeiffer)