What a mission to Venus could tell us about Earth's moon

Launching a mission to the planet Venus might help reveal exactly how the moon formed nearly 4.5 billion years ago, one prominent researcher says.

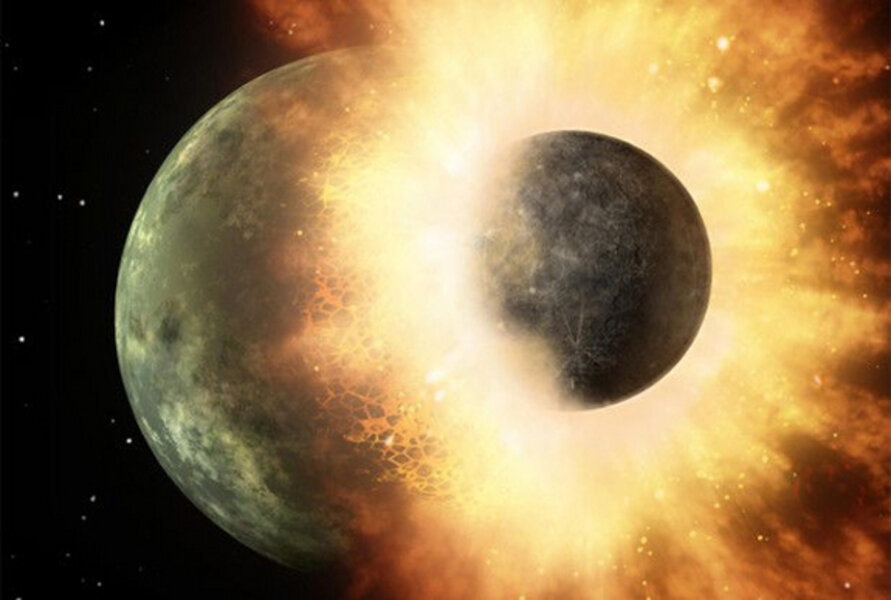

Planetary scientists think the moon coalesced out of material blasted into space when a large object slammed into the proto-Earth in the early days of the solar system. But the details of this mega-collision remain fuzzy, with several different theories competing to explain how it all went down.

The original giant-impact theory, which has been in development since the 1970s, posits that a Mars-size object struck Earth with a slow and glancing blow long ago. In this scenario, the moon formed from a disk of material ejected largely from the mysterious impactor's mantle. [The Moon: 10 Surprising Lunar Facts]

But studies of lunar rocks have shown that the moon and Earth's outer portions are extremely similar geochemically, posing a serious problem for the "canonical" giant-impact idea.

"It is improbable that the impactor had the same composition as the early Earth," Robin Canup, of the Southwest Research Institute in Boulder, Colo., wrote in a commentary published today (Dec. 4) in the journal Nature.

"The oxygen isotope composition of Mars, for example, differs from that of the Earth by more than a factor of 50," Canup added. "If the impactor was as different from Earth as Mars is, its signature would still be detectable in the moon, even after a giant collision."

So Canup and other scientists have devised new models that attempt to mesh better with the available data. Last year, for example, Canup suggested that the giant impact may have involved two planets that were each about half as massive as the present-day Earth. Material from the impactor and the target would each constitute about half of the newly formed moon and the newly enlarged Earth after such a collision, she said.

Another 2012 study, authored by Matija Cuk of the SETI (Search for Extraterrestrial Intelligence) Institute in Mountain View, Calif., and Sarah Stewart of Harvard, suggests that the smashup may well have involved a Mars-size impactor — if Earth were spinning much more rapidly than it is today.

If Earth's day had been just two to three hours long back then, Cuk and Stewart determined, the planet could well have thrown off enough material to form the moon (which is 1.2 percent as massive as Earth). A gravitational interaction between Earth's orbit around the sun and the moon's orbit around Earth could then have put the brakes on the planet's spin rate after the impact, eventually producing a 24-hour day.

At the moment, it's tough to know which of these various theories best represents reality, Canup and other researchers say. That's partly because the likely composition of the impactor remains very much up in the air — a problem that a newmission to Venus might be able to solve.

"We do not know the isotopic composition of Venus, the planet most similar to Earth in both mass and distance from the sun," Canup wrote. "If Venus' composition proves similar to that of Earth and the moon, Mars would then seem to be an outlier, and an impactor composition akin to Earth's would be more probable, removing many objections to the canonical impact."

"Determining the isotopic composition of Venus' key elements will probably require a mission to the planet," she added. "Such a tantalizing prospect reminds us how much there is still to learn in our solar-system backyard."

Other pieces of data — such as more precise measurements of the isotopic composition of lunar rocks and pieces of Earth's mantle — would also help resolve the mystery of the moon's formation, Canup said. She's confident that a clearer picture of the dramatic event will emerge relatively soon.

"Overall, we are very close — we know giant impacts are extremely efficient at making moons (and, in particular, iron-depleted ones, which is one of the most salient features of our moon), and that it seems difficult to form Earth-sized planets without such large impact events," Canup told SPACE.com via email.

"So the general picture is in good shape," she added. "The issue is deciphering what the detailed chemical relationships between the Earth and moon are telling about the specific type of impact. My guess is that it will probably take a few years of a combination of additional modeling efforts and more data to get this sorted out."

Follow Mike Wall on Twitter @michaeldwall and Google+. Follow us @Spacedotcom, Facebook or Google+. Originally published on SPACE.com.

- Moon Master: An Easy Quiz for Lunatics

- How the Moon Evolved - Video Guided Tour

- 10 Coolest Moon Discoveries

Copyright 2013 SPACE.com, a TechMediaNetwork company. All rights reserved. This material may not be published, broadcast, rewritten or redistributed.