China touts prowess of moon rover, scientists just want to know what's there

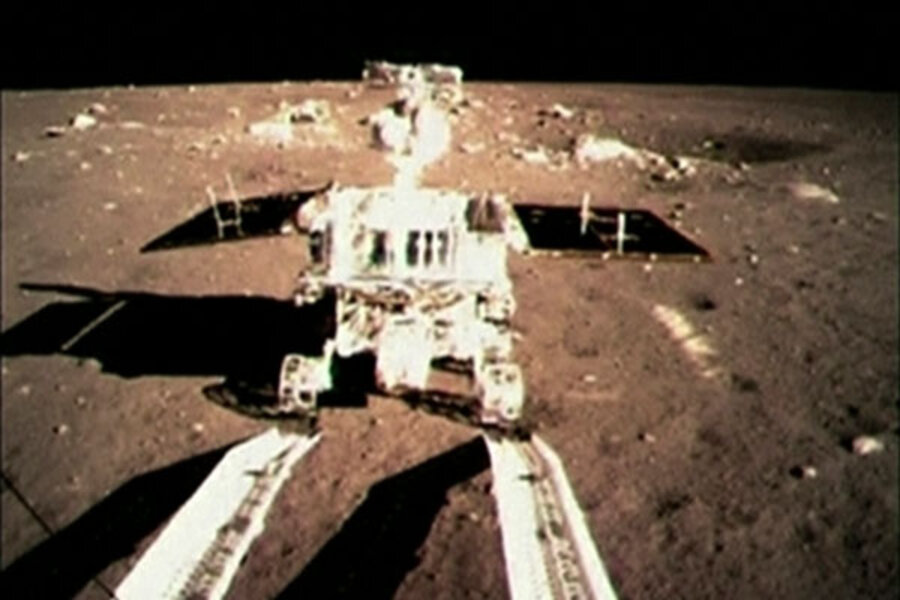

With China's Jade Rabbit running loose in the moon's Sea of Rains, lunar scientists on Earth are eager to see what the 290-pound rover finds as it analyzes the terrain and rocks.

The rover and its 1.5-ton lander touched down Saturday – the first soft landing on the moon in 37 years. The duo landed on a moonscape with volcanic rocks thought to be far younger than any sampled elsewhere in the handful of locations US astronauts and Soviet landers visited in the 1960s and '70s.

During the past decade, the US, Europe, India, China, and Japan have sent orbiters to the moon. With the information from these missions, “We know know something about the surface on a global scale,” says Carle Pieters, a planetary geologist at Brown University in Providence, R.I., who was the lead scientist for an instrument aboard India's Chandrayaan-1 orbiter that mapped minerals on the lunar surface.

But for the first time in nearly 40 years, a robotic geologist will be exploring a specific location, one that ranks as “a very exciting place,” Dr. Pieters says, if the flurry of e-mails ricocheting among lunar scientists since the landing is any indication.

The craft landed inside Mare Imbrium, an enormous impact crater that over time filled with lava that cooled to form the crater's basaltic floor. The craft landed at a location that hosts what appears to be some of the youngest basalts seen anywhere on the lunar surface and with a much different composition.

This means that the mission holds the potential to open a window on an important period in the moon's geological history – the coda to a prolonged period of episodic volcanic activity that began when the moon was pummeled and heated by impactors during a period known as the Late Heavy Bombardment. That bombardment ended some 3.9 billion years ago.

So while the Chinese framed this mission around their interest in returning samples and eventually mining lunar minerals, much of the excitement outside China focuses on other potential findings. The mission could help fill wide gaps in researchers' understanding of the moon, whose history is turning out to be far more complicated than it seemed only a decade ago.

Information about the instruments on the rover has been short on details, but Jade Rabbit is said to carry ground-penetrating radar and two instruments that can analyze the chemical makeup of rocks and soils, according to Paul Spudis, a staff scientist at the Lunar and Planetary Institute in Houston.

“This is a very sophisticated mission. This is not just a simple, bare-bones platform to get a picture and declare victory,” he says.

The rover's radar may be able to analyze so-called "wrinkle ridges," which are thought to form as the basalt cooled and contracted. They appear in crater basins on the moon as well as on Mars. Depending on the radar's design, it also should be able to explore the interface between the layer of chewed-up material at the surface, called the regolith, and the lava flows that might be only a few tens of meters below the surface, Dr. Spudis says. And it may be able to capture images of the interface between the basalt layer and the original floor of the crater hundreds of meters below the surface.

These measurements would help reveal the crater's volcanic history, which remains a mystery.

The Imbrium basin might have had one large volcanic vent at the bottom “that erupted magma for tens of millions of years, kind of like turning on your bath tub until it was full,” says Mark Robinson, a planetary geologist at Arizona State University in Tempe and the lead investigator for LROC, a high-resolution camera aboard NASA's Lunar Reconnaissance Orbiter.

Or the basin could have filled gradually from a series of small eruptions that happened over 500 million to a billion years or longer. Or the answer could fall somewhere in between.

By gathering information on layering in the subsurface basalts, researchers can sort among the possible eruption scenarios to find the one that best fits the observations.

Jade Rabbit also is said to carry an imaging spectrometer and an alpha-particle X-ray spectrometer – a staple of planetary rovers. Combined, the two yield information on the mineral and chemical makeup of the rocks they encounter.

Not far from the landing site, images reveal an impact crater perhaps 40 feet across. Analyzing the rocks between the rover and the crater rim could yield insights into the composition of the bedrock beneath the regolith.

As a rover heads toward a crater rim, the rocks it encounters come from ever deeper in the crater. At a distance roughly equal to the crater's diameter, it passes rock that was part of the original surface. At the crater rim, it meets rock from the crater's deepest point. It's like having a core sample from the crust with layers already set out in order as a rover drives along.

The basalts in this crater appear to be enriched in titanium compared with basalts found elsewhere. Data on titanium levels, as well as of other metals in Mare Imbrium, would serve as a reality check to improve the accuracy of the measurements taken remotely, Dr. Robinson adds.

Having wheels on the moon after such a long hiatus is “very exciting for the lunar-science community, and I hope it's very exciting to just about everybody in the world,” Robinson says. “There's a rover driving around on the moon.”

[Editor's Note: In the original version of this article, the last paragraph incorrectly identified the moon.]