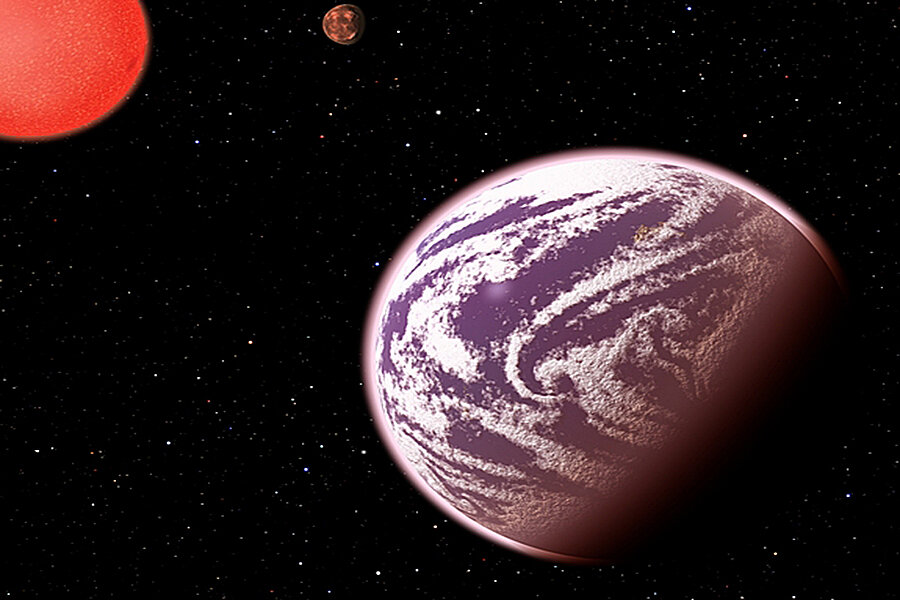

Astronomers spot a big puffball of a planet

Loading...

Astronomers have spotted a hotter and puffier version of Earth circling a distant star.

The oddball exoplanet candidate KOI-314c is located about 200 light-years away and is roughly the same mass as Earth, but its extremely thick atmosphere makes the world about 60 percent larger than our home planet, scientists say.

"This planet might have the same mass as Earth, but it is certainly not Earth-like," study lead author David Kipping, of the Harvard-Smithsonian Center for Astrophysics (CfA), said in a statement. "It proves that there is no clear dividing line between rocky worlds like Earth and fluffier planets like water worlds or gas giants." [The Strangest Alien Planets (Gallery)]

Kipping announced the discovery of KOI-314c, which was made using observations by NASA's Kepler space telescope, today (Jan. 6) at the 223rd meeting of the American Astronomical Society in Washington.

Kepler was designed to spot exoplanets by noticing the telltale brightness dips they cause when crossing the face of, or transiting, their host stars' faces from the telescope's perspective. KOI-314c is the first transiting Earth-mass planet ever found and is the lightest alien world to have both its mass and size measured, researchers said.

The planet orbits its parent red dwarf star once every 23 days. The discovery team estimates KOI-314c's surface temperature to be 220 degrees Fahrenheit (104 degrees Celsius), meaning it's probably too hot to support life as we know it.

KOI-314c is likely surrounded by a hydrogen-helium atmosphere hundreds of miles thick, researchers said. This atmosphere may once have been even thicker, with much of it being boiled off into space over the eons by the red dwarf's radiation.

KOI-314c has a sibling planet called KOI-314b, which completes one orbit every 13 days. To calculate the mass of KOI-314c, the study team measured how the planet's gravity affects the movement of its neighbor world.

This technique, known as transit timing variations (TTV), is a departure from the usual method, in which astronomers measure the wobbles a planet's gravity induces in its parent star. TTV was first used successfully in 2010 but has a great deal of potential going forward, especially with regard to low-mass alien planets, researchers said.

"We are bringing transit timing variations to maturity," Kipping said.

Kipping and his team discovered KOI-314c by serendipity as they were poring over Kepler data looking for satellites of alien planets, known as exomoons.

"When we noticed this planet showed transit timing variations, the signature was clearly due to the other planet in the system and not a moon," Kipping said. "At first we were disappointed it wasn't a moon, but then we soon realized it was an extraordinary measurement."

Follow Mike Wall on Twitter @michaeldwall and Google+. Follow us @Spacedotcom, Facebook or Google+. Originally published on SPACE.com.

- Gallery: A World of Kepler Planets

- 9 Exoplanets That Could Host Alien Life

- Alien Planet Quiz: Are You an Exoplanet Expert?

Copyright 2014 SPACE.com, a TechMediaNetwork company. All rights reserved. This material may not be published, broadcast, rewritten or redistributed.