Ancient sea monsters had black skin, scales, say scientists

Some of the largest beasts in the ancient seas had black skin or scales, new research finds.

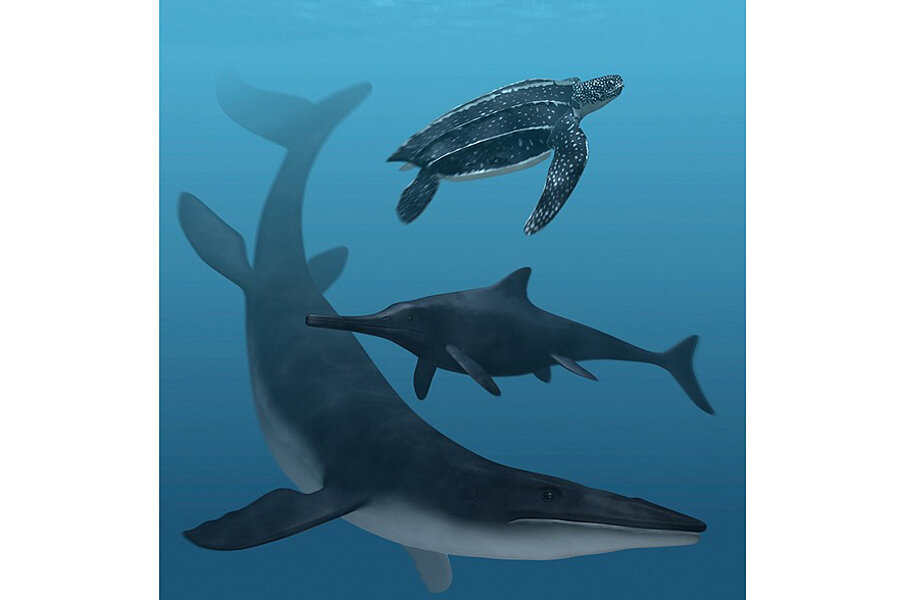

Ancient leatherback turtles, toothy predators called mosasaurs and dolphinlike reptiles called ichthyosaurs all had black pigmentation, researchers report today (Jan. 8) in the journal Nature. The findings come from an analysis of preserved skin from each of these creatures.

The animals' blackness likely helped them in a variety of ways, said study researcher Johan Lindgren, a mosasaur expert at Lund University in Sweden. "We suggest … that they used it not only as camouflage and UV protection, but also to be able to regulate their body temperature," Lindgren told LiveScience. [Sea Monster Album: See Images of Extinct Mosasaurs]

Ancient colors

The study isn't the first to delve into the color of ancient creatures. Paleontologists have found that Microraptor, a small winged dinosaur from 130 million years ago, had black, crowlike feathers. The "dino-bird" Archaeopteryx had wing feathers with a black-and-white pattern, too, according to a 2012 study detailed in the journal Nature Communications. The color of ancient feathers is somewhat controversial, however, with some scientists suggesting the fossilization process might distort the pigment-containing organelles in the feathers.

But marine animal color was uncharted territory. Some fossils of extinct sea monsters have been found with black "halos" around the bones, suggesting remnants of skin. Anatomical analysis suggested these remnants were, in fact, melanosomes, the tiny packets of pigments that give skin, feathers and hair their color. Melanosomes contain melanin, a dark brown or black pigment. In fact, the black pigment eumelanin is extremely persistent in the environment, Lindgren said, so the presence of melanosomes may be the reason these skin halos survived.

Lindgren and his colleagues conducted a microscopic analysis of the fossilized skin of a 55-million-year-old leatherback turtle, an 86-million-year-old mosasaur and a 190-million year-old ichthyosaur. Mosasaurs were reptilian, fishlike apex predators in the Cretaceous seas. Ichthyosaurs were also marine reptiles, but with their long snouts, they resembled modern dolphins.

Dark and dangerous

A microscopic look at the fossils showed oval bodies consistent with the look of melanosomes. To confirm that the oval bodies were melanosomes, the researchers used a technique called energy-dispersive X-ray microanalysis, which focuses X-rays on the sample. The reaction of the sample depends on its chemical makeup. This analysis showed that the tiny ovals were associated with the preserved skin film, but not with the sediment around it, suggesting they are really melanosomes and not microbial contamination.

To understand how ancient sea creatures benefited from black skin and scales, Lindgren and his colleagues turned to the only sea turtle that stays black into adulthood: the modern leatherback turtle (Dermochelys coriacea). These turtles have a broad range, all the way into the Arctic circle, and the color seems to help them trap heat from sunlight in the same way that black asphalt gets hot on a bright day, Lindgren said. Black pigments also protect the skin from damage from UV rays (also known as sunburn). Mosasaurs, ichthyosaurs and ancient may have gotten a similar advantage from their coloration.

Black skin and scales may also have helped these creatures stay stealthy in the dark seas. Living leatherback turtles are dark on top with light underbellies, so they blend in with the depths from above and with the sunlight at the surface from below. Many ocean-dwelling creatures show this coloration pattern, Lindgren said, but the fossil skin samples from the ancient turtle and mosasaur are too small to say for sure whether they shared countershading camouflage.

Ichthyosaurs are a different story. Some ichthyosaur fossils consist of skeletons surrounded completely by an "envelope" of dark material. If these envelopes prove to be entirely skin remains, Lindgren said, they would suggest that ichthyosaurs were completely black. That coloration would make them like modern sperm whales, which dive deep into murky waters — as ancient ichthyosaurs also may have done.

"Of course, that may be a coincidence, but it's an interesting similarity that they share," Lindgren said.

The techniques used in the study may also be able to resolve debate over the coloration of land animals, he said, differentiating whether suspected melanosomes come from the fossil or from microbes.

Follow Stephanie Pappas on Twitter and Google+. Follow us @livescience, Facebook & Google+. Original article onLiveScience.

- Image Gallery: Ancient Monsters of the Sea

- Dangers in the Deep: 10 Scariest Sea Creatures

- Image Gallery: 25 Amazing Ancient Beasts

Copyright 2014 LiveScience, a TechMediaNetwork company. All rights reserved. This material may not be published, broadcast, rewritten or redistributed.