How did live birth evolve? Surprising fossil find offers clues.

Loading...

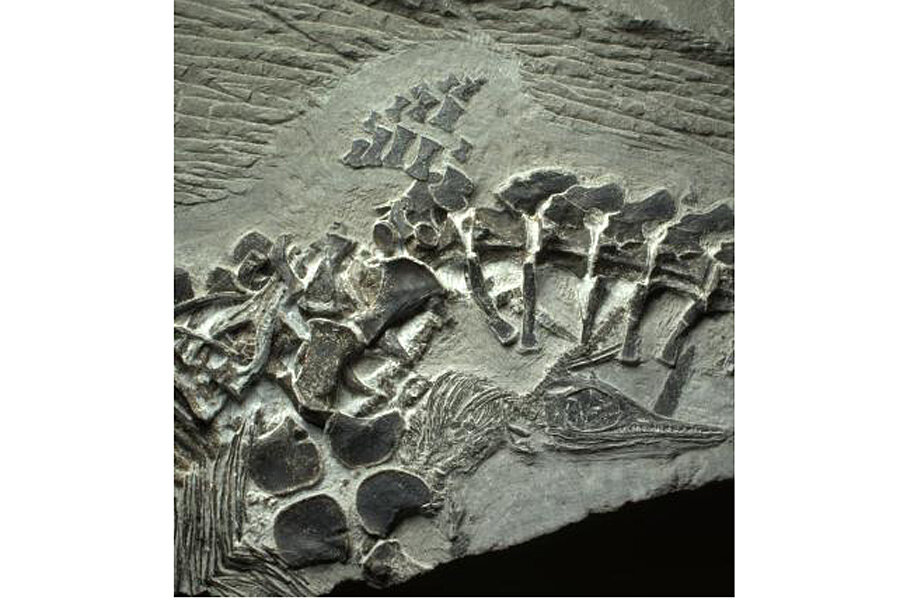

A new fossil that captures both birth and death reveals the earliest ancestors of the giant prehistoric sea predators called ichthyosaurs birthed their babies headfirst, according to a new study.

The fossil of an ancient Chaohusaurus mother that likely died while in labor also suggests that reptilian live birth only evolved on land, researchers report today (Feb. 12) in the journal PLOS ONE.

Ichthyosaurs were top ocean predators during the age of the dinosaurs. Sleek, streamlined swimmers that grew as long as a bus, they had teeth-filled snouts and enormous eyes for snatching prey. These air-breathing carnivores arose from land reptiles that moved into the water from land during the early Triassic period, between 251 million and 247 million years ago. (The Triassic period follows one of the biggest mass extinctions on Earth, which killed 96 percent of marine species and 70 percent of land species.) [Image Gallery: Ancient Monsters of the Sea]

Previously found fossils of pregnant ichthyosaurs had already revealed the reptiles carried live embryos, not eggs. And one spectacular fossil of a Stenopterygius ichthyosaur in "childbirth," from the Jurassic period, between 201 million and 145 million years ago, showed at least one species had newborns come out tail-first.

However, researchers didn't know whether the earliest ichthyosaurs also gave birth headfirst or tail-first. Most air-breathing marine creatures that bear live young, such as whales and dolphins, birth their babies tail-first, so the newborns don't suffocate during labor. But on land, babies tend to come out headfirst. And the earliest whales, which also evolved from land mammals, birthed their newborns headfirst.

The new fossil confirms that the first ichthyosaur babies came out headfirst, the study reports. The ichthyosaur mother died with three young: one outside the mother, one half-emerged headfirst from her pelvis and one still inside, waiting to be born. Because of the burial positions, it's unlikely the babies were expelled from the mother after death, the researchers said.

"The reason for this animal dying is likely difficulty in labor," said Ryosuke Motani, lead study author and a paleobiologist at the University of California, Davis. Motani believes the first baby was born dead, and the mother may have died of a labor complication from the second, which is stuck half-in, half-out of her body. "Obviously, the mother had some complications," he said.

The skeleton was a lucky find. It was hidden in a rock slab with a Saurichthys fish fossil, and was only discovered when the fish fossil was prepared in the team's lab in China. (The two fossils aren't from the same time period, the researchers said.)

The Chaohusaurus fossil, from one of the oldest ichthyosaur species, is about 10 million years older than other fossil embryos from reptiles found so far.

The specimen is now at the Anhui Geological Museum in Hefei, China. The team recovered more than 80 new ichthyosaur skeletons during a recent field expedition to a fossil quarry in south Majiashan, China.

Earliest newborns

Live birth evolved independently in more than 140 different species, including about 100 reptiles. Other extinct aquatic reptiles that gave birth to live young include the plesiosaur and the mosasaur; in 2011, scientists discovered a pregnant plesiosaur, a marine reptile, which lived some 78 million years ago.

The new ichthyosaur fossil pushes back the known records of live birth to the earliest appearance of marine reptiles 248 million years ago, during the beginning of the Mesozoic era.

Until now, researchers thought live birth first appeared in marine reptiles after they took to the seas, Motani said. The ichthyosaur fossil counters this assumption, by providing an evolutionary link to the headfirst, terrestrial style of childbirth.

"This land-style of giving birth is only possible if they inherited it from their land ancestors," Motani told Live Science. "They wouldn't do it if live birth evolved in water."

And because ichthyosaurs evolved from land reptiles, the discovery suggests that land reptiles also bore live young in the earliest Mesozoic, Motani said. The oldest fossil evidence for live birth in land reptiles is no more than 125 million years old, more than 100 million years younger than the new fossil discovery.

Email Becky Oskin or follow her @beckyoskin. Follow us @livescience, Facebook & Google+. Original article on Live Science.

- Image Gallery: Photos Reveal Prehistoric Sea Monster

- Rumor or Reality: The Creatures of Cryptozoology

- In Photos: Top 10 Deadliest Animals

Copyright 2014 LiveScience, a TechMediaNetwork company. All rights reserved. This material may not be published, broadcast, rewritten or redistributed.