Sriracha sauce reveals what makes humans special

Loading...

A saucy video produced by the American Chemical Society (ACS) is stoking the flames breathed by Sriracha hot sauce enthusiasts, by focusing attention on why people like stuff that hurts.

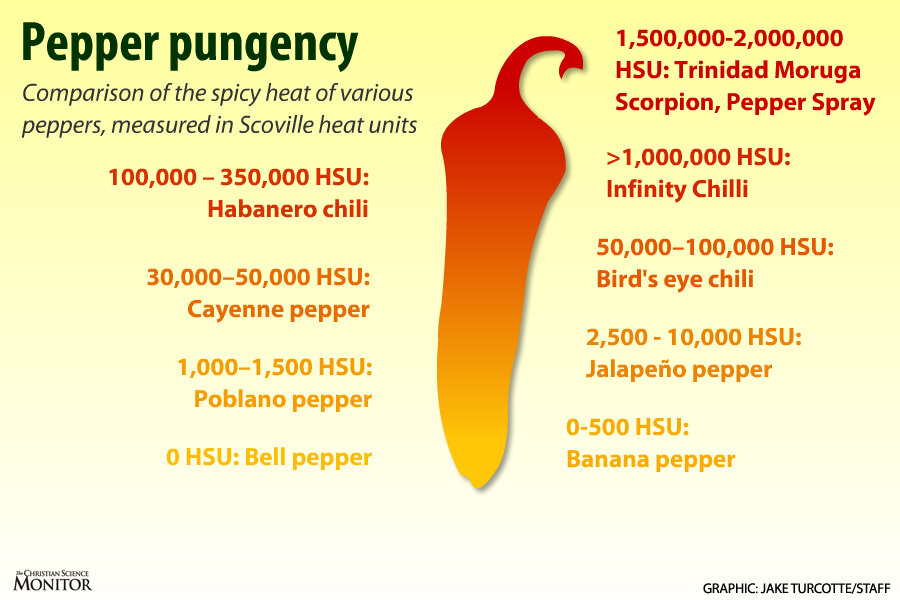

Our mouths are full of heat receptor proteins that begin to produce a scalding sensation in response to temperatures above 109 degrees Farenheit, explains the ACS. And those same receptors, called TRPV1, are also triggered by compounds called capsaicinoids, which are present in chili peppers. That's why a bite of habañero feels so much like a premature sip of soup.

In response to these alarms, the body releases a pain-killing endorphin rush, which is one way to explain why people keep coming back to Sriracha.

The bright red condiment, made of fresh chili peppers, vinegar, garlic, sugar, salt, and two preservatives, has gotten a lot of press lately. For one thing, the quaintly bottled sauce has acquired cult status in the US, decades after arriving in the country via Thai and Vietnamese cuisines.

Even more recently, Huy Fong Goods, the company that began manufacturing Sriracha sauce in the US, has been doing battle in Los Angeles Superior Court over complaints that an L.A. pepper-crushing plant emits a harmfully spicy odor.

But scientists have been exploring why people like hot sauce for decades.

In 1980, the same year Huy Fong Foods opened a small factory in Los Angeles's Chinatown, two scientists who reckoned that chili pepper was the most widely consumed spice in the world, received a National Science Foundation grant to study how its charm works on Mexicans and Americans.

Maybe, they hypothesized, chili-eating desensitized those cranky protein receptors, turning it into a a burn-free experience. Or maybe people learned to like the burn.

"Chili likers are not insensitive to the irritation that it produces," found Paul Rozin and Deborah Schiller, of the University of Pennsylvania. "They come to like the same burning sensation that deters animals and humans that dislike chili; there is a clear hedonic shift."

What exactly is hedonic shift?

"The enjoyment of the irritation may result from the user's appreciation that the sensation and the body's defensive reaction to it are harmless," explained the scientists. Of 28 American subjects, 22 said they were as sensitive as they always had been to chili, but that they had come to like the hot sensation that they once disliked.

"Eating of chili, riding on roller coasters, taking very hot baths, and many other human activities can be considered instances of thrill seeking or enjoyment of 'constrained risks," found Drs. Rozin and Schiller.

Several studies in the 1990s examined novelty-seeking tendencies at a genetic level, and even identified a gene (D4DR) where it seems to reside in some people, and not in others. But it is not clear whether pepper-enjoyment follows the same genetic lines.

What does seem clear is that these 'benignly masochistic' activities," as Rozin and Schiller described the likes of chili eating and bungee jumping, seem to distinguish humans from other animals. "There are no well-documented cases, to our knowledge, of animals that clearly come to enjoy innately negative stimuli or bodily defensive reactions," they wrote.