On the journey from Asia to North America, some turned back, say linguists

Loading...

For ancient migrants, Beringia – the region that once bridged Alaska and Siberia – wasn't a one-way street.

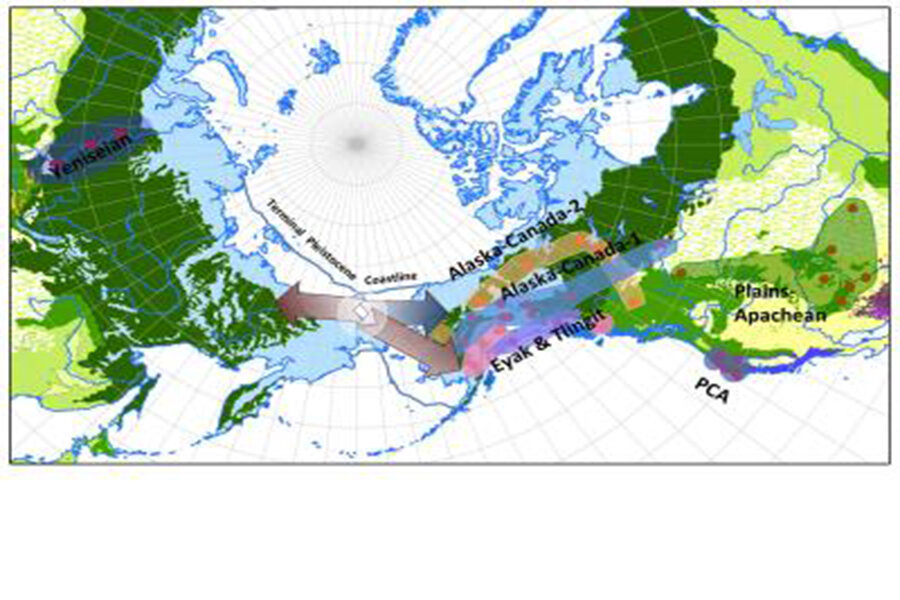

Instead, people moved out of the region, with some journeying back westward to Central Asia and the rest heading eastward to North America, according to a paper titled "Linguistic Phylogenies Support Back-Migration from Beringia to Asia" published in the open-access journal PLOS ONE on March 12.

Researchers Mark Sicoli of Georgetown University and Gary Holton from University of Alaska Fairbanks examined shared characteristics between North American Na-Dene languages and the Yeniseian languages of Central Siberia, and constructed a language "tree" by incorporating "computational phylogenetic tools developed primarily in evolutionary biology."

In phylogenetic analysis, a tree is plotted to study evolutionary relationships between organisms. Drs. Sicoli and Holton used the same technique to show the relationships between languages.

Sicoli said in a press release, "we used computational phylogenetic methods to impose constraints on possible family tree relationships modeling both an Out-of-Beringia hypothesis and an Out-of-Asia hypothesis and tested these against the linguistic data. We found substantial support for the out-of-Beringia dispersal adding to a growing body of evidence for an ancestral population in Beringia before the land bridge was inundated by rising sea levels at the end of the last ice age."

Researchers such as Edward Vajda, a linguist at Western Washington University had earlier suggested that some sort of common ancestry existed between Proto-Na-Dene and Proto-Yeniseian languages.

Based on such previous findings and their analysis, this scientists suggest that both the Na-Dene and the Yeniseian languages came from a language family known as the Dené–Yeniseian, which, they say, originated in Beringia.

"Our results support that a Dene-Yeniseian connection more likely represents radiation out of Beringia with back-migration into central Asia than a migration from central or western Asia to North America," researchers noted in their paper.

But Dr. Vajda says that he is a bit skeptical of the out-of-Beringia hypothesis based on similarities shared between the different languages.

"To show that languages are related in a family you need to find lots of evidence of shared retentions inherited from a common ancestor (a 'proto-language')," he told the Monitor. "Within a family of related languages, to understand the history of the spread and diversification of the family, you have to find shared innovations characteristic of some languages and not of the rest before you can demonstrate family-internal subgrouping. You can't show this convincingly by just counting up the number of apparent commonalities."

But Sicoli says that the paper doesn't just use "counting" as a method of analysis. It also uses another set of analysis called the "Bayesian modeling, which is rather more robust statistically," he says."We analyzed the languages for the presence or absence of dozens of features, such as sets of sound contrasts and which categories are coded by noun and verb morphology. Rather than simply counting up similarities, Bayesian phylogenetics analyzes the probabilities for family tree shapes given the data and does take into account how shared innovations support branch structuring and subgroupings within a tree."

The statistical analysis provides substantial support for the Out-of-Beringia model, Sicoli says.