'Strange' dinosaur was closest thing to a bird without being one

The fossil remains of an ostrich-size creature that roamed the riverine wetlands of North America some 67 million years ago is shedding light on one of the most mysterious groups of major dinosaurs paleontologists have unearthed.

Partial skeletons of the newly described creature, christened Anzu wyliei, came from two sites in the Dakotas. A composite built from the finds was formally described for the first time in a paper published online Wednesday by the journal PLOS ONE.

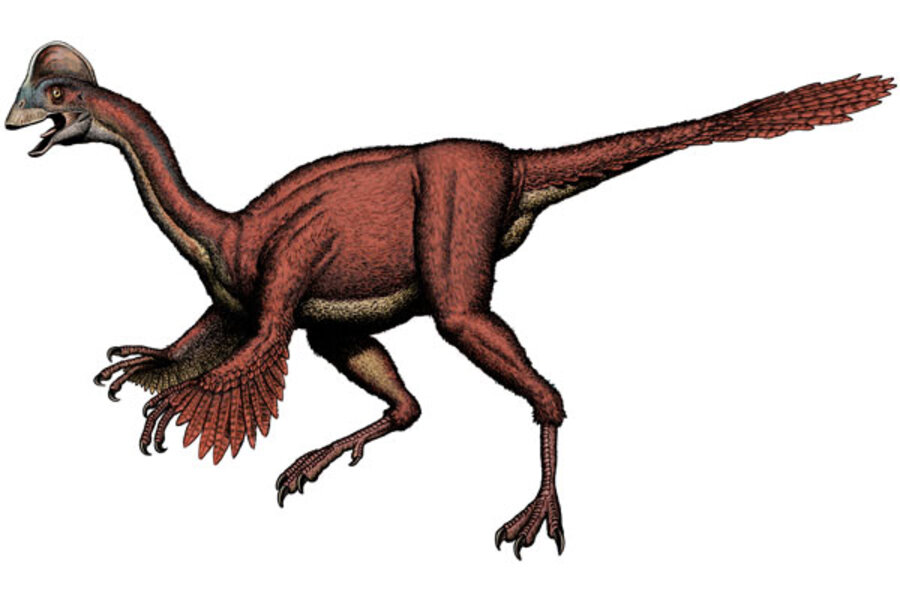

The animal – an intriguing blend of traits common to birds and to crocodiles – stretched some 11 feet from the tip of its beak to the tip of its tail. Researchers estimate that it weighed in at between 440 and 660 pounds.

Beyond the novelty of the animal itself, the find is adding to evidence that on the eve of extinction, dinosaurs may have been far more diverse than some paleontologists believe.

Evidence has mounted that dinosaurs were done in by a collision between Earth and a large asteroid or comet 66 million years ago. This has prompted a debate over whether the event merely delivered the coup de grâce to an already ailing dino demographic or whether it snuffed a rich, otherwise robust assemblage of animals.

The message sent by this and other similar findings is that the state of Dinosauria at this time was healthy.

Paleontologists with the Burpee Museum of Natural History in Rockford, Ill., have uncovered another partial skeleton of A. wyliei from eastern Wyoming, says Tyler Lyson, a paleontologist who discovered parts of the skeletons analyzed in Wednesday's report. And last December, Royal Ontario Museum paleontologist David Evans and colleagues published their analysis of a new species of meat-eater they named Acheroraptor temertyorum.

This, plus other fossils that have been collected but have yet to be formally described, indicate that the diversity of dinosaurs was doing fine until the very end, Dr. Lyson says.

The team's new dinosaur "is a really cool dinosaur; it's a really neat looking animal," he says. "But it lends further support to the catastrophic demise of dinosaurs, which I think it pretty significant."

Although A. wyliei falls into the same broad group of theropods – known as maniraptors, a group that also gave rise to modern birds – it doesn't fall into the direct lineage that led to modern birds, says Matthew Lamanna, assistant curator for vertebrate paleontology at the Carnegie Museum of Natural History in Pittsburgh.

But, he adds, "this thing is just about as close as you can be to a bird without being a bird yourself. You can see the shared evolutionary heritage with birds all over the skeleton."

Among its birdlike traits, beyond the hollow bones: feathers, inferred from 125 million-year-old relatives found in China that are covered with feathers; a beak with no teeth; long arms; a bony crest on its head; and a tendency to brood in nests. On the other hand, the long, bony tail, the large hands, and the large claws associated with them are decidedly unbirdlike.

"It's a very strange bird-reptile hybrid," says Hans-Dieter Sues, curator of vertebrate paleontology at the National Museum of Natural History.

Based on the type of sediment covering the fossils, the team suggests that A. wyliei lived along river flood plains. As for food, the team suggests that A. wyliei was a generalist, gnoshing on plants, small animals, and perhaps the eggs of other animals.

The rock formation yielding the new species dates to the end of the Cretaceous period. This new animal is the second new species to come from this formation in a year, with more on the way, researchers say.

Until now, evidence for A. wyliei's evolutionary clan, formally known as caenagnathids, has been fragmentary, says Dr. Lamanna. This made it hard to describe the creature, its place on dinosaurs' evolutionary tree, its environment, or its likely diet.

"Since 1924, we've had little bits and pieces of this predominantly North American group – a pair of hands here, an isolated foot there, a lower jaw there – but we haven't had the whole thing," says Dr. Lamanna, who is the lead author of a paper describing the animal.

But in a collaborative effort with Lyson, Dr. Sues, and Emma Schachner of the University of Utah, Lammana has been able to assemble a nearly complete skeleton of A. wyliei.

The remains come from a geological feature known as the Hell Creek Formation, which runs beneath North and South Dakota. In the 1990s, two of the specimens were uncovered by commercial fossil hunters in at a site in South Dakota's Harding County and ultimately acquired by the Carnegie Museum.

Meanwhile, Lyson and a team of volunteers discovered the third set of remains among the badlands in North Dakota's Slope County, about 50 miles north of Harding County. The team found broken pieces of bone that had become exposed as a hillside eroded, Lyson recalls.

"We followed the trail up the hill, and sticking out the side of the hill we could see these bones," he says. They were hollow, a dead giveaway that the group had found remains of meat-eaters.

Team members wrapped an exposed bone in a plaster cast, then dug it out of the hillside, leaving the fossil with its equivalent of a root ball's worth of soil to protect the rest of it.

After removing the soil, "I was able to determine that it was something new. I've seen skeletons of every dinosaur that's ever been found in the Hell Creek Formation. This was unlike anything else," he says.

The Carnegie Museum had acquired the South Dakota specimens to beef up its exhibit of Cretaceous animals, notes Sues, who at the time was working as curator at the Carnegie Museum. After he moved to Washington, Sues and Lammana teamed up to study the remains. Later, at a paleontology meeting, they learned that Lyson and colleague Dr. Schachner were analyzing the Slope County discovery.

In something relatively rare in the competitive field of paleontology, the four agreed to pool their fossils to build one specimen. The team was able to combine its fossil resources because the specimens contained enough overlapping types of bones to ensure they all belonged to the same species, Lyson explains.