Paleontologists discover oldest known pterodactyloid

By the end of the Jurassic period, most primitive species of the order Pterosaurs became extinct. But one lineage of the order evolved rather quickly into pterodactyloids, and managed to survive.

These were some of the largest creatures ever to take to the skies, says University of South Florida paleontologist Brian Andres.

A 162.7 million-year-old fossil of the oldest pterodactyloid species unearthed in northwest China sheds light on how such species adapted to their environments.

Chris Sloan, formerly with National Geographic and now president of media company Science Visualization, first spotted the fossil in 2001.

At that time researchers had mistakenly associated the bones with two-legged dinosaur called a theropod. Later detailed examination of the delicate fossil bones revealed that the species not only belonged to the order Pterosaur (the first reptiles to develop active flight) but was also a new pterodactyloid species altogether.

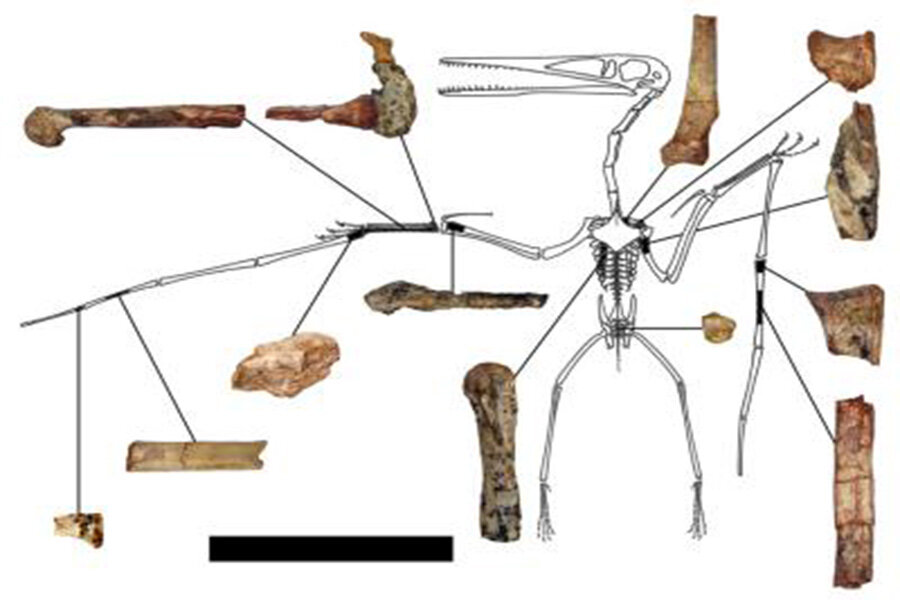

Fossil remains of the newly discovered pterodactyloid dubbed Kryptodrakon progenitor, which translates into 'Hidden Dragon,' indicate that the pterodactyloids differed from other Pterosaurs in certain morphological characteristics. The wing of the dragon was supported by the fourth finger and the first bone of that finger (known as metacarpal) was long compared to that of other Pterosaurs. The tail had become relatively smaller, which could be more aerodynamically efficient. Also, the fifth toe on the hind foot was reduced. Basically, by the end of the Jurassic period "they went crazy," says James Clark, paleontologist with the George Washington University, who was involved with the research.

The remains of Kryptodrakon progenitor were found in red mudstone, which could have been associated with a river channel in the past, Dr. Clark says. The deposits found in an inland area indicate that pterodactyloids originated, lived and evolved in terrestrial environments.

With an estimated wingspan of about 4.5 feet, the species lived around the time of the Middle-Upper Jurassic boundary. They gradually evolved into gigantic flying creatures, some as big as small airplanes and taller than giraffes, and became extinct 66 million years ago, along with the dinosaurs and many other marine reptiles, says Dr. Andres, who was involved with the study.

These morphological features may have helped them to survive longer than other species of the same order, say the researchers.

The findings appear in a paper titled "The Earliest Pterodactyloid and the Origin of the Group," published in the journal Current Biology.