How a new seafloor map could aid in the search for Malaysian Airlines Flight 370

Loading...

The deep-sea search for missing Malaysian Airlines Flight 370 could get a boost from a new, more detailed map of the seafloor west of Australia.

The missing plane left Kuala Lumpur International Airport on a scheduled flight to Beijing on March 8 and is believed to have crashed in the southeast Indian Ocean after veering off course and running out of fuel. Surface searches have turned up no conclusive signs of debris. Ocean floor mapping is underway and could take months to complete, the Australian Transport Safety Bureau said in a May 26 statement. [Facts About Flight 370: Passengers, Crew & Aircraft]

The surface of Mars is better mapped than the details of the seafloor in the suspected crash region, said a report published today (May 27) in Eos, the weekly newspaper of the American Geophysical Union. Depth measurements by ship cover only 5 percent of the vast ocean region, wrote two ocean mapping experts with the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA).

"It is a very complex part of the world that is very poorly known," report co-author Walter Smith said in a statement.

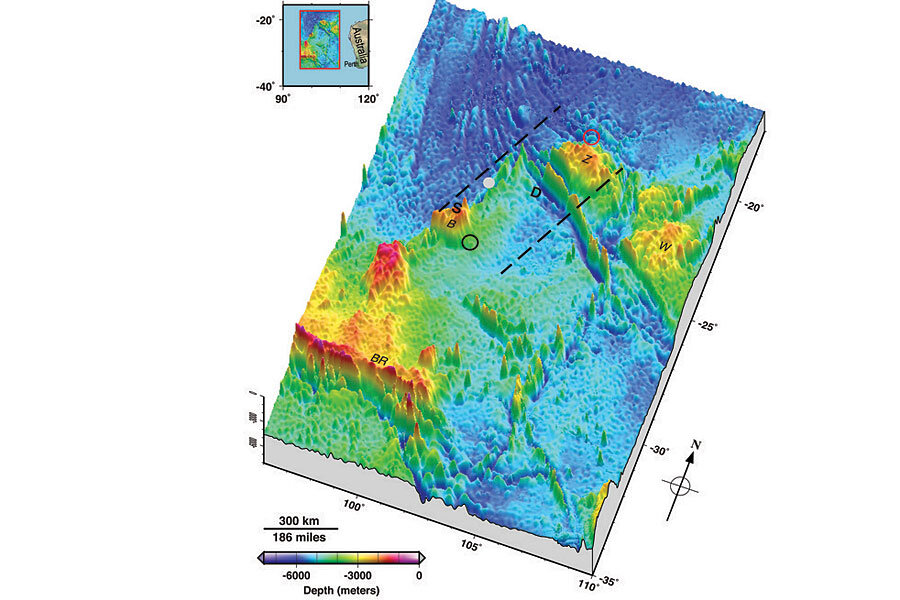

Smith and co-author Karen Marks created a more precise map of the Flight 370 search area using satellite altimetry data. Satellite measurements of small bumps and dips in the ocean surface provide a model of the topography of the seafloor. The data is publicly available from the General Bathymetric Chart of the Oceans, or GEBCO, the authors said.

While still only a rough guide to the ocean bottom's ridges and mountains, the new map could help searchers forecast the path of floating debris and decide what kind of tech to use when plumbing the ocean depths, the researchers said.

For example, the map reveals that the region's deepest point is an estimated 4.9 miles (7.9 kilometers) below the ocean surface. However, the unmanned Bluefin-21 sub currently scouring the seafloor for acoustic signals has a depth limit of about 2.8 miles (4.5 km).

The new seafloor topography covers an area of 1,243 miles by 870 miles (2,000 km by 1,400 km) — the region where searchers detected what could be acoustic signals from the airplane's black boxes.

A Chinese survey ship, Zhu Kezhen, is also currently mapping the deep ocean floor in this region. After that ship completes its survey, commercial operators will use towed sonar equipment to search for debris from the missing plane.

Email Becky Oskin or follow her @beckyoskin. Follow us @livescience, Facebook & Google+. Original article on Live Science.

- Flight 370: Photos of the Search for Missing Malaysian Plane

- Gallery: Lost in the Bermuda Triangle

- Flight 370: The Tech Behind the Hunt for Missing Malaysian Plane

Copyright 2014 LiveScience, a TechMediaNetwork company. All rights reserved. This material may not be published, broadcast, rewritten or redistributed.