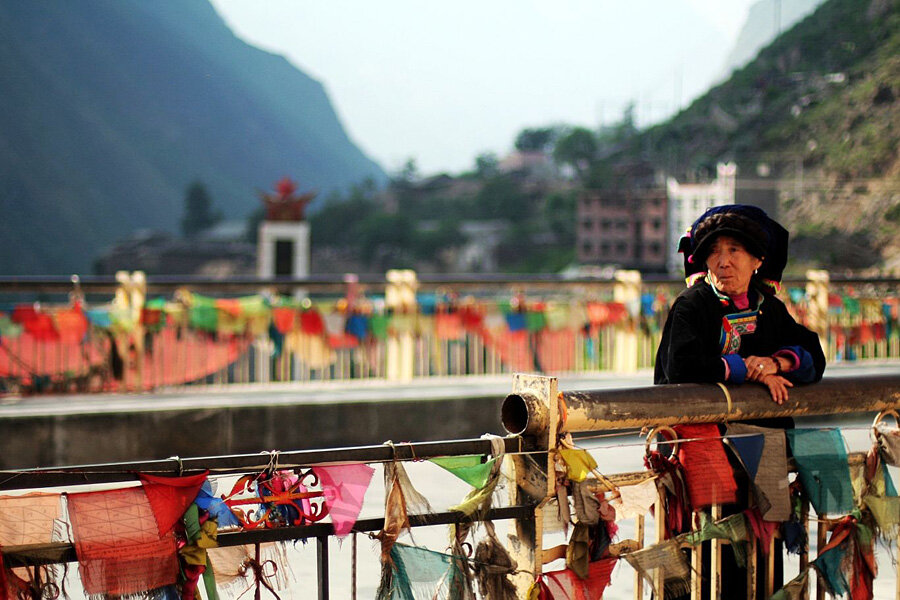

Tibetans inherited high-altitude gene from extinct human lineage, say scientists

Loading...

| Washington

How do Tibetans thrive in high-altitude, low-oxygen conditions that would make others wither? Well, they may have received some help from an unexpected source.

Scientists said on Wednesday many Tibetans possess a rare variant of a gene involved in carrying oxygen in the blood that they likely inherited from an enigmatic group of extinct humans who interbred with our species tens of thousands of years ago.

It enables Tibetans to function well in low oxygen levels at elevations upwards of 15,000 feet (4,500 meters) like the vast high plateau of southwestern China.

This version of the EPAS1 gene is nearly identical to one found in Denisovans, a lineage related to Neanderthals - but is very different from other people today.

Denisovans are known from a single finger bone and two teeth found in a Siberian cave. DNA testing on the 41,000-year-old bone indicated Denisovans were distinct from our species and Neanderthals.

"Our finding may suggest that the exchange of genes through mating with extinct species may be more important in human evolution than previously thought," saidRasmus Nielsen, a computational biology professor at the University of California, Berkeley and the University of Copenhagen, whose study appears in the journal Nature.

Our genome contains residual genetic fragments from other organisms like viruses as well as species like Neanderthals with which early modern humans interbred. The researchers called their study the first to show that a gene from an archaic human species has helped modern humans adjust to different living conditions.

"Such exchange of genes with other species may in fact have helped humans adapt to new environments encountered as they spread out of Africa and into the rest of the world," said Nielsen.

Asan Ciren, a researcher with China's BGI genomics center, added, "The genetic relationship or blood relationship between modern humans and archaic hominins is a hot topic of the current paleoanthropology."

The researchers said early modern humans trekking out of Africa interbred with Denisovans in Eurasia en route to China. Their descendants harbor a tiny percentage of Denisovan DNA.

Genetic studies show nearly 90 percent of Tibetans have the high-altitude gene variant, along with a small percentage of Han Chinese, who share a common ancestor with Tibetans. It is seen in no other people.

The researchers conducted genetic studies on 40 Tibetans and 40 Han Chinese and performed a statistical analysis showing that the gene variant almost certainly was inherited from the Denisovans.

The gene regulates production of hemoglobin, a protein in red blood cells that carries oxygen. It is turned on when blood oxygen levels drop, stimulating more hemoglobin production.

At elevations above 13,000 feet (4,000 meters), the common form of the gene boosts hemoglobin and red blood cell production, causing dangerous side effects. The Tibetans' variant increases hemoglobin and red blood cell levels only modestly, sparing them these effects.

(Reporting by Will Dunham; Editing by Grant McCool)