Is Pluto really a planet? NASA probe could rekindle debate.

Loading...

The world will get its first good look at Pluto a little more than a year from now, possibly reigniting the debate over the object's planetary status.

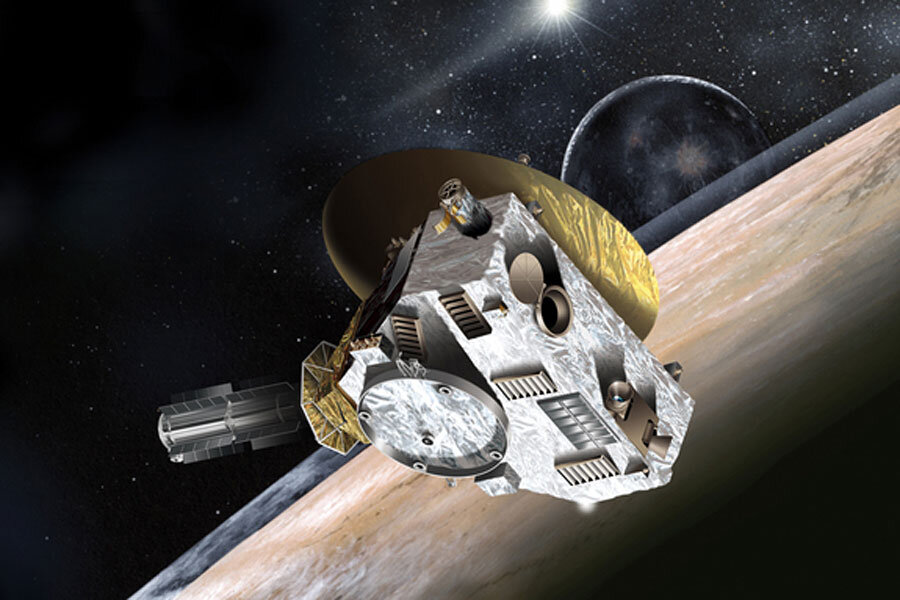

In July 2015, NASA's New Horizons probe will fly by frigid and faraway Pluto, which was demoted to "dwarf planet" in 2006 by the International Astronomical Union. (Despite the ruling, many scientists still regard Pluto as a planet, as this recent video incorporating audio from the 2013 Pluto Science Conference shows.)

The encounter will mark the first "unveiling" of a major solar system body since 1989, when NASA's Voyager 2 spacecraft flew by the ice giant Neptune, Pluto's nearest planetary neighbor. [NASA's New Horizons Flight to Pluto in Pictures]

"For most people, going to a brand-new planet — not back to Mars to rove a different place, but to a whole new place for the first time, and to see it revealed — is going to be an experience unlike anything they've ever seen," New Horizons principal investigator Alan Stern, of the Southwest Research Institute in Boulder, Colorado, told Space.com earlier this year. "I think we're going to have a chance to really enthuse people."

Pluto: planet or not?

Pluto had been known as the solar system's ninth planet since its 1930 discovery. But that all changed when the International Astronomical Union (IAU) — the organization responsible for giving "official" scientific names to celestial objects — decided to revise its definition of "planet" in August 2006.

That decision was based in part upon the growing realization that Pluto is far from the only large object in the Kuiper Belt, the ring of icy bodies that orbits the sun beyond Neptune. The biggest jolt came in 2005, when a team of astronomers led by Mike Brown of Caltech found Eris, a Kuiper Belt body that seemed to be even larger than Pluto. [Photos of Pluto and its Moons]

So on Aug. 24, 2006, the IAU came up with a new definition of "planet": a body that orbits the sun without being another object's satellite, is large enough to be rounded into a sphere by its own gravity (but not so big that it sparks nuclear fusion reactions, like a star) and has "cleared its neighborhood" of most other orbiting bodies.

Pluto was demoted to the newly created category of "dwarf planet" because it failed to meet the "clear your neighborhood" criterion.

Some astronomers largely embraced the new classification, but others, such as Stern, were not at all happy. The neighborhood-clearing requirement particularly displeased Stern.

"In no other branch of science am I familiar with something that absurd," Stern told Space.com in 2011. "A river is a river, independent of whether there are other rivers nearby. In science, we call things what they are based on their attributes, not what they're next to."

Stern doesn't have a problem with the term "dwarf planet." He just thinks that dwarf planets should be included in the ranks of "true" planets, along with rocky worlds such as Earth and gas giants like Saturn and Neptune. Excluding the dwarfs, which are likely incredibly numerous, seems like an attempt by the IAU to keep the number of true planets down to a manageable size, he said in 2011.

"That's not a very scientific way of going about it, since we have countless numbers of stars, galaxies, asteroids and everything else," Stern said.

New views of Pluto

The New Horizons spacecraft launched in January 2006. Its historic flyby next summer may spur further conversation about the planethood of Pluto, which orbits the sun at an average distance of 3.65 billion miles (5.87 billion kilometers) — so far away that the object looks like a fuzzy ball in the best Hubble Space Telescope photos.

The encounter will shine a very bright spotlight on Pluto, which remains largely mysterious more than 80 years after its discovery.

For example, scientists didn't know the dwarf planet had any moons until 1978, when they spotted the big satellite Charon orbiting Pluto. At 750 miles (1,207 km) across, Charon is about half as wide as Pluto itself.

Recent observations by Hubble revealed four more moons, all of them tiny. Astronomers spotted Nix and Hydra in 2005, and discovered Kerberos and Styx in 2011 and 2012, respectively.

New Horizons will search for additional moons around Pluto, and determine whether or not the dwarf planet has a ring system. The craft will also map the surface composition and characterize the geology of both Pluto and Charon, before flying on and continuing to explore the Kuiper Belt.

The New Horizons mission should greatly increase researchers' understanding of Pluto, the Kuiper Belt and ice dwarfs in general, mission officials say.

"The United States has made history by being the first nation to reach every planet from Mercury to Neptune with a space probe," officials write on the New Horizons website, which is maintained by Johns Hopkins University's Applied Physics Laboratory. "The New Horizons mission to Pluto and the Kuiper Belt — the first NASA launch to a 'new' planet since Voyager more than 30 years ago — allows the U.S. to complete the reconnaissance of the solar system."

Follow Mike Wall on Twitter @michaeldwall and Google+. Follow us @Spacedotcom, Facebook orGoogle+. Originally published on Space.com.

- Pluto Quiz: How Well Do You Know the Dwarf Planet?

- What Are Pluto's Moons Named? | Video

- Pluto's 5 Moons Explained: How They Measure Up (Infographic)

Copyright 2014 SPACE.com, a TechMediaNetwork company. All rights reserved. This material may not be published, broadcast, rewritten or redistributed.