Paleontologists discover world's oldest known muscles

Loading...

A fossilized creature found in Canada probably didn't go to the gym, but it may be the oldest animal known to have muscles, a new study finds.

The specimen, which is approximately 560 million years old, is thought to be a relative of sea anemones and jellyfish, and contains fibrous bundles that appear to be muscle tissue, an important adaptation in the evolution of animals, according to a new study detailed today (Aug. 26) in the journal Proceedings of the Royal Society B.

"It's confirmation that muscular organisms were present roughly 560 million years ago," said study co-author Alex Liu, a paleontologist at the University of Cambridge in England. [Marine Marvels: Spectacular Photos of Sea Creatures]

Historically, scientists believed animal evolution began 540 million years ago during the Cambrian Explosion, a period of rapid evolution when most major animal groups first appear in the fossil record.

But in recent decades, researchers have uncovered large, complex fossils and traces of animal activity from the late Ediacaran Period, which spanned from about 580 million to 541 million years ago.

The idea that animals first appeared before the Cambrian is also supported by studies that compare genetic data from different animals to determine how far back in time they diverged, in order to calibrate "molecular clocks," Liu told Live Science. Those clocks have gradually become more and more accurate, with some estimates suggesting animals first arose 700 million years ago, in the Cryogenian Period, he said.

In addition, the presence of chemical compounds, called biomarkers, serve as telltale signs that animals existed before the Cambrian, Liu said.

Most of the fossils found in the Ediacaran Period don't have features that clearly identify them as animals rather than plants, fungi or other life forms. But the new fossil, found in Newfoundland, Canada, differs from all other fossils of that time, Liu said.

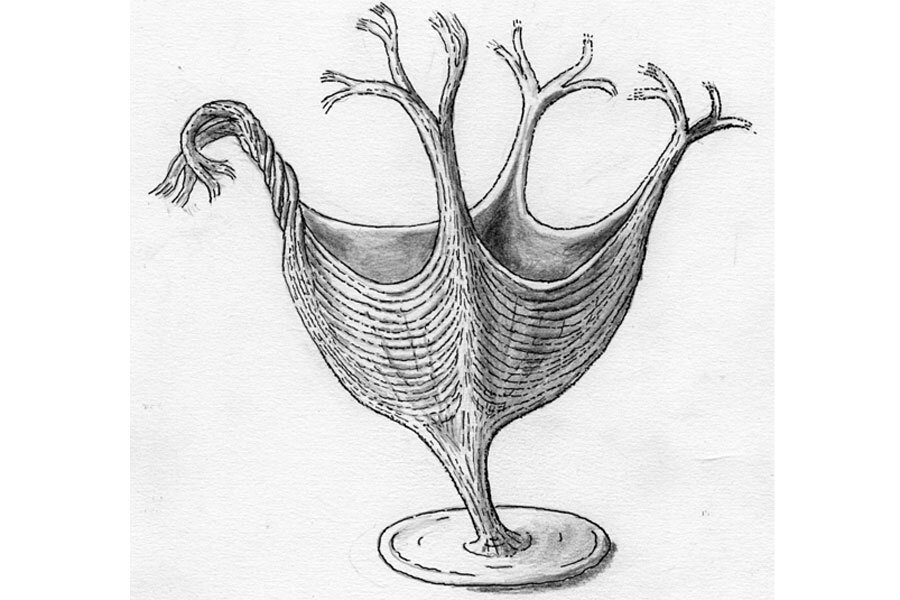

The creature's body consists of a circular disc that it likely used to anchor itself to the ocean floor. The disc is connected by a short stalk to a sheetlike body made of fibrous bundles — believed to be muscles — arranged in a four-fold symmetry.

The fossil represents a new genus and species called Haootia quadriformis. Liu and his colleagues classified it as a type of cnidarian — a phylum of aquatic animals that includes corals, sea anemones and jellyfish — because of its resemblance to modern cnidarians, especially the stalked jellyfish Lucernaria quadricornis.

The researchers ruled out other possible explanations for the fiber bundles, such as the movement of tectonic plates or sediments, or the conditions of fossilization. The complexity and arrangement of the bundles, and the fact that some of them appear to be contracted, all suggest that the structures are indeed muscles, Liu said. The researchers compared the bundles to muscle tissue in modern cnidarians and found them to be similar, he added.

In addition to being the oldest fossil with muscles, the newfound cnidarian also serves as a calibration point for the molecular clocks that show when different species diverged from each other, Liu said.

The development of muscles was a critical event in animal evolution. Except for sponges, all animals rely on muscles to move from place to place, to escape from predators, to feed and to reproduce. Vertebrates are the most extreme example: "Everything is dependent on muscle tissue being able to contract and extend," from breathing to digestion, Liu said.

Follow Tanya Lewis on Twitter and Google+. Follow us @livescience, Facebook & Google+. Original article on Live Science.

- Image Gallery: 25 Amazing Ancient Beasts

- Image Gallery: Jellyfish Rule!

- Dangers in the Deep: 10 Scariest Sea Creatures

Copyright 2014 LiveScience, a TechMediaNetwork company. All rights reserved. This material may not be published, broadcast, rewritten or redistributed.