Boffins discover colossal black hole within tiny dwarf galaxy

Loading...

Astronomers have just discovered the smallest known galaxy that harbors a huge, supermassive black hole at its core.

The relatively nearby dwarf galaxy may house a supermassive black hole at its heart equal in mass to about 21 million suns. The discovery suggests that supermassive black holes may be far more common than previously thought.

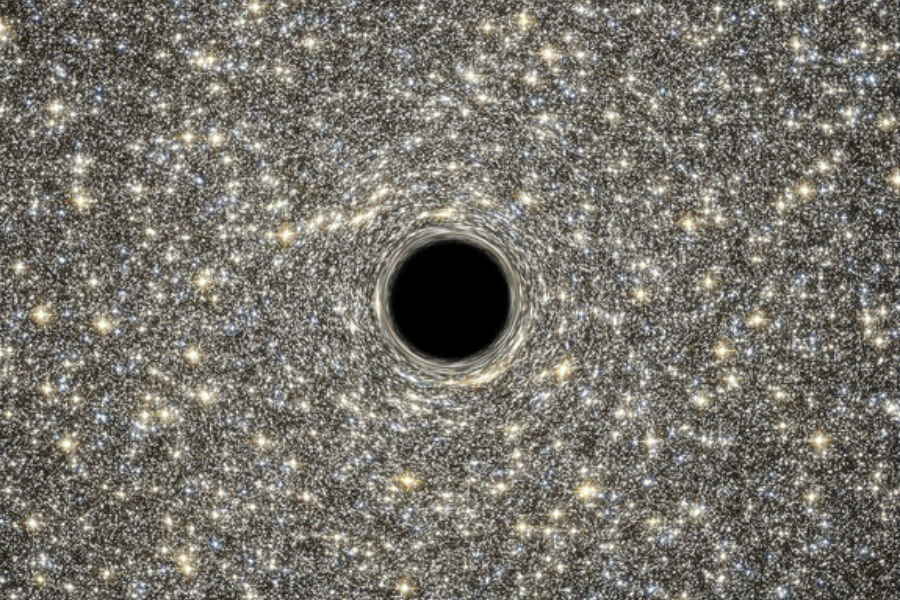

A supermassive black hole millions to billions of times the mass of the sun lies at the heart of nearly every large galaxy like the Milky Way. These monstrously huge black holes have existed since the infancy of the universe, some 800 million years or so after the Big Bang. Scientists are uncertain whether dwarf galaxies might also harbor supermassive black holes. [Watch a Space.com video about the new dwarf galaxy finding]

"Dwarf galaxies usually refer to any galaxy less than roughly one-fiftieth the brightness of the Milky Way," said lead study author Anil Seth, an astronomer at the University of Utah in Salt Lake City. These galaxies span only several hundreds to thousands of light-years across, much smaller than the Milky Way's 100,000-light-year diameter, and they "are much more abundant than galaxies like the Milky Way," Seth said.

The researchers investigated a rarer kind of dwarf galaxy known as an ultra-compact dwarf galaxy; such galaxies are among the densest collections of stars in the universe. "These are found primarily in galaxy clusters, the cities of the universe," Seth told Space.com.

Now, Seth and his colleagues have discovered that an ultra-compact dwarf galaxy may possess a supermassive black hole, which would make it the smallest galaxy known to contain such a giant.

The astronomers investigated M60-UCD1, the brightest ultra-compact dwarf galaxy currently known, using the Gemini North 8-meter optical-and-infrared telescope on Hawaii's Mauna Kea volcano and NASA's Hubble Space Telescope. M60-UCD1 lies about 54 million light-years away from Earth. The dwarf galaxy orbits M60, one of the largest galaxies near the Milky Way, at a distance of only about 22,000 light-years from the larger galaxy's center, "closer than the sun is to the center of the Milky Way," Seth said.

The scientists calculated the size of the supermassive black hole that may lurk inside M60-UCD1 by analyzing the motions of the stars in that galaxy, which helped the researchers deduce the amount of mass needed to exert the gravitational field seen pulling on those stars. For instance, the stars at the center of M60-UCD1 zip at speeds of about 230,000 mph (370,000 km/h), much faster than stars would be expected to move in the absence of such a black hole.

The supermassive black hole at the core of the Milky Way has a mass of about 4 million suns, taking up less than 0.01 percent of the galaxy's estimated total mass, which is about 50 billion suns. In comparison, the supermassive black hole that may lie in the core of M60-UCD1 appears five times larger than the one in the Milky Way, and also seems to make up about 15 percent of the dwarf galaxy's mass, which is about 140 million suns.

"That is pretty amazing, given that the Milky Way is 500 times larger and more than 1,000 times heavier than the dwarf galaxy M60-UCD1," Seth said in a statement.

Astronomers have debated the nature of ultra-compact dwarf galaxies for years — whether they were extremely massive clusters of stars that were all born together, or whether they were the centers or nuclei of large galaxies that had their outer layers stripped away during collisions with other galaxies. These new findings hint that ultra-compact dwarf galaxies are the stripped nuclei of larger galaxies, because star clusters do not host supermassive black holes.

The researchers suggest M60-UCD1 was once a very large galaxy, with maybe 10 billion stars, "but then it passed very close to the center of an even larger galaxy, M60, and in that process, all the stars and dark matter in the outer part of the galaxy got torn away and became part of M60," Seth said in a statement. "That was maybe as much as 10 billion years ago. We don't know."

Eventually, M60-UCD1 "may merge with the center of M60, which has a monster black hole in it, with 4.5 billion solar masses — more than 1,000 times bigger than the supermassive black hole in our galaxy," Seth said in a statement. "When that happens, the black hole we found in M60-UCD1 will merge with that monster black hole."

The astronomers suggest the way stars move in many other ultra-compact dwarf galaxies hints that they may host supermassive black holes, as well. All in all, the scientists suggest that ultra-compact dwarf galaxies could double the number of supermassive black holes known in the nearby regions of the universe. The researchers are participating in ongoing projects that may provide conclusive evidence for supermassive black holes in four other ultra-compact dwarfs.

The scientists detailed their findings in the Sept. 18 issue of the journal Nature.

Follow us @Spacedotcom, Facebook and Google+. Original article onSpace.com.