How can there be ice on Mercury?

Loading...

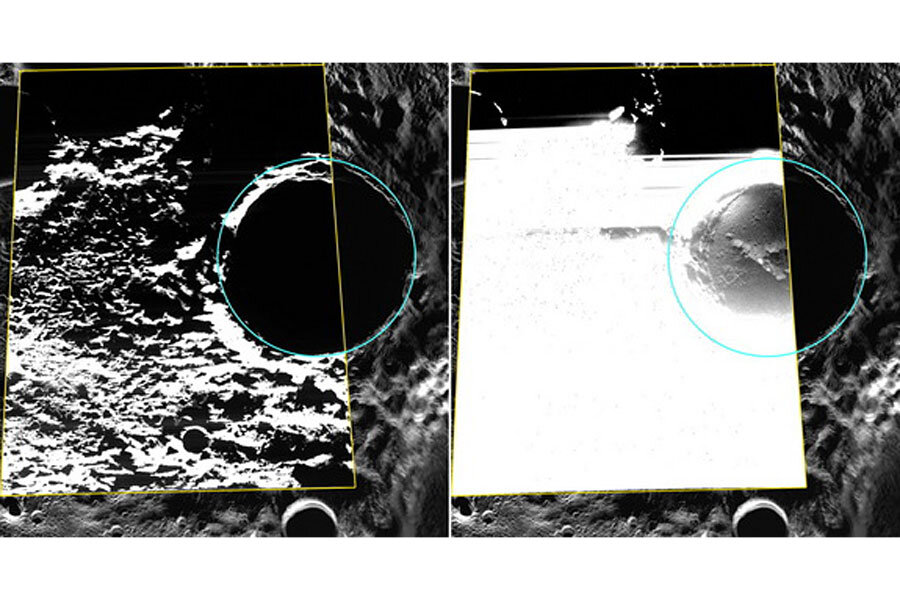

The first-ever photos of water ice near Mercury's north pole have come down to Earth, and they have quite a story to tell.

The images, taken by NASA's MESSENGER spacecraft (short for MErcury Surface, Space ENvironment, GEochemistry, and Ranging), suggest that the ice lurking within Mercury's polar craters was delivered recently, and may even be topped up by processes that continue today, researchers said.

More than 20 years ago, Earth-based radar imaging first spotted signs of water ice near Mercury's north and south poles — a surprise, perhaps, given that temperatures on the solar system's innermost planet can top 800 degrees Fahrenheit (427 degrees Celsius). [Water Ice On Mercury: How It Was Found (Video)]

In late 2012, MESSENGER confirmed those observations from orbit around Mercury, discovering ice in permanently shadowed craters near the planet's north pole. MESSENGER scientists announced the find after integrating results from thermal modeling studies with data gathered by the probe's hydrogen-hunting neutron spectrometer and its laser altimeter, which measured the reflectance of the deposits.

And now the MESSENGER team has captured optical-light images of the ice for the first time, by taking advantage of small amounts of sunlight scattered off the craters' walls.

"There is a lot new to be learned by seeing the deposits," said study lead author Nancy Chabot, instrument scientist for MESSENGER’s Mercury Dual Imaging System and a researcher at the Johns Hopkins University Applied Physics Laboratory in Laurel, Maryland, in a statement.

For example, the texture of the ice at the bottom of Mercury's 70-mile-wide (113 kilometers) Prokofiev Crater suggests that the material was put in place relatively recently rather than billions of years ago, researchers said.

Images of other craters back up this notion. They show dark deposits, believed to be frozen organic-rich material, covering ice in some areas, with sharp boundaries between the two different types of material.

"This result was a little surprising, because sharp boundaries indicate that the volatile deposits at Mercury’s poles are geologically young, relative to the time scale for lateral mixing by impacts," Chabot said.

Earth's moon also harbors water ice inside permanently shadowed polar craters, but its deposits look different from those on Mercury, researchers said. This could be because Mercury's ice was delivered more recently.

"If you can understand why one body looks one way and another looks different, you gain insight into the process that's behind it, which in turn is tied to the age and distribution of water ice in the solar system," Chabot said. "This will be a very interesting line of inquiry going forward."

The new study was published online today (Oct. 15) in the journal Geology.

Follow Mike Wall on Twitter @michaeldwall and Google+. Follow us @Spacedotcom, Facebook orGoogle+. Originally published on Space.com.

- Planet Mercury: Simple Facts, Tough Quiz

- Most Enduring Mysteries of Mercury

- NASA's Messenger Mission to Mercury (Infographic)

Copyright 2014 SPACE.com, a TechMediaNetwork company. All rights reserved. This material may not be published, broadcast, rewritten or redistributed.