After a century on ice, a notebook sheds light on an Antarctic disaster

Loading...

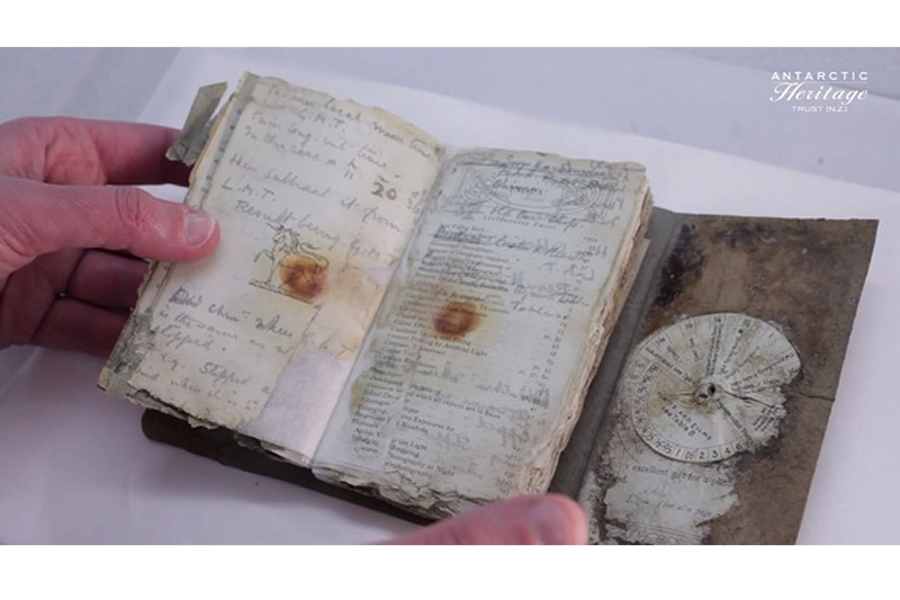

Hidden in ice for more than 100 years, the photography notebook of a British explorer on Captain Robert Falcon Scott's ill-fated expedition to Antarctica has been found.

The book belonged to George Murray Levick, a surgeon, zoologist and photographer on Scott's 1910-1913 voyage. Levick might be best remembered for his observations of Cape Adare's Adélie penguins (and his scandalized descriptions of the birds' "depraved" sex lives). The newly discovered book also shows he kept fastidious notes, scrawled in pencil, about the photographs he took at Cape Adare.

Levick's "Wellcome Photographic Exposure Record and Dairy 1910" had been left behind at Captain Scott's last expedition base at Cape Evans. Conservationists discovered the notebook outside the hut during last year's summer melt. [See Photos of the Lost Antarctic Notebook]

"It's an exciting find," Nigel Watson, executive director of the New Zealand-based Antarctic Heritage Trust, said in a statement. "The notebook is a missing part of the official expedition record. After spending seven years conserving Scott's last expedition building and collection, we are delighted to still be finding new artifacts."

The book has notes detailing the date, subjects and exposure details from his photographs. In his notes, Levick refers to a self-portrait he took while shaving in a hut at Cape Adare and shots he took of his fellow crewmembers as they set up theodolites (instruments for surveying) and fish traps and sat in kayaks.

Levick was one of six men in Scott's Northern Party, who summered (1911-1912) at Cape Adare and survived the winter of 1912 in a snow cave when their ship was unable to reach them. Levick was not part of the team that accompanied Scott on his doomed quest to be the first to reach the South Pole. After an arduous two-and-a-half month trek, Scott and his crew did make it to the South Pole on Jan. 17, 1912. But they discovered that the Norwegian explorer Roald Amundsen had beat them to it. Scott and his team died on the way back to their base, faced with a blizzard and dwindling supplies.

One hundred years of damage from ice and water dissolved the notebook's binding. The pages were separated and digitized before the book was put back together again with new binding and sent back to Antarctica, where the Antarctic Heritage Trust maintains 11,000 artifacts at Cape Evans. Earlier this year, conservationists with the group developed century-old photo negatives left in Scott's base by members of Ernest Shackleton's last Antarctic Expedition.

Follow Megan Gannon on Twitter and Google+. Follow us @livescience, Facebook & Google+. Original article on Live Science.

- Race to the South Pole in Images

- Image Gallery: Sex Habits of Penguins

- Scott's Last Expedition: Images From His Doomed South Pole Trek

Copyright 2014 LiveScience, a TechMediaNetwork company. All rights reserved. This material may not be published, broadcast, rewritten or redistributed.