How did birds lose their teeth?

Birds — like anteaters, baleen whales and turtles — don't have teeth. But this wasn't always the case. The common ancestor of all living birds sported a set of pearly whites 116 million years ago, a new study finds.

In the study, researchers looked at the mutated remains of tooth genes in modern birds to figure out when birds developed "edentulism" — an absence of teeth. Ancient birds have left only a fragmented fossil record, but studying the genes of modern birds can help clarify how the bird lineage has changed over time.

"DNA from the crypt is a powerful tool for unlocking secrets of evolutionary history," Mark Springer, a professor of biology at the University of California, Riverside and one of the study's lead researchers, said in a statement.

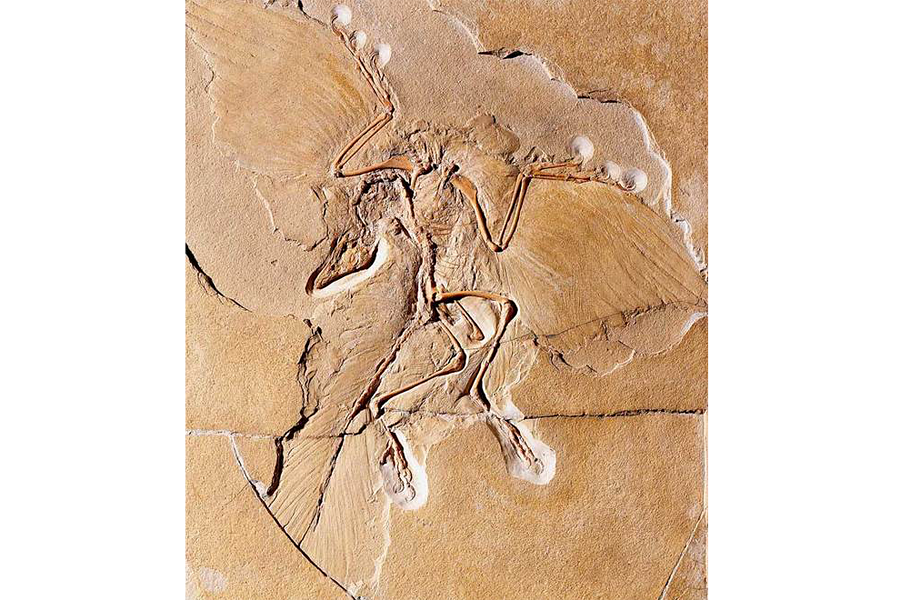

Modern birds have curved beaks and a hearty digestive tract that help them grind and process food. But the 1861 finding of the fossil bird Archaeopteryx in Germany suggested that birds descended from toothed reptile ancestors, Springer said. And scientists now know that birds evolved from theropod dinosaurs, carnivorous beasts such as Tyrannosaurus rex, which had a mouth full of sharp teeth.

But no one knew exactly what happened to the teeth in the evolution of these animals from then until now. "The history of tooth loss in the ancestry of modern birds has remained elusive for more than 150 years," Springer said. [8 Foods for Healthy Teeth]

In the new study, the researchers wondered whether the bird lineage lost its teeth in a single event, meaning the common ancestor of all birds did not have teeth, or whether edentulism happened independently, in different lines of birds throughout history, the researchers said.

To find out, they investigated the genes that govern tooth production. In vertebrates, tooth formation involves six genes that are crucial for the formation of enamel (the hard tissue that coats teeth) and dentin (the calcified stuff underneath it).

The researchers looked for mutations that might inactivate these six genes in the genomes of 48 bird species, which represent almost every order of living birds. A mutation in dentin- and enamel-related genes that was shared among bird species would indicate that their common ancestor had lost the ability to form teeth, the researchers said.

They found that all of the bird species had the same mutations in dentin- and enamel-related genes.

"The presence of several inactivating mutations that are shared by all 48 bird species suggests that the outer enamel covering of teeth was lost around 116 million years ago," Springer said.

The researchers also found mutations in the in the enamel and dentin genes of other vertebrates that don't have teeth or enamel, including turtles, armadillos, sloths, aardvarks and pangolins, which look like scaly anteaters.

The closest living modern reptile relative of birds is the alligator, Springer said. "All six genes are functional in the American alligator," Springer said.

This tooth finding is one of many that came out of a large-scale scientific effort to study the evolution of birds. The findings of that effort were published today (Dec. 12) in the journal Science, and in several other journals.

Follow Laura Geggel on Twitter @LauraGeggel. Follow Live Science @livescience, Facebook & Google+. Original article on Live Science.

- Images: These Downy Dinosaurs Sported Feathers

- Pretty Bird: Images of a Clever Parrot

- In Photos: Birds of Prey

Copyright 2014 LiveScience, a TechMediaNetwork company. All rights reserved. This material may not be published, broadcast, rewritten or redistributed.