Why is NASA so interested in Europa?

After years of asking, encouraging, and downright pleading, NASA chief Charles Bolden finally got to announce the good news from President Obama's proposed NASA budget:

NASA has been working toward a Europa mission for over 15 years, and this budget – if passed by Congress – marks the official go-ahead to move from proposals to more concrete mission planning, wrote NASA officials in a summary of the proposed budget.

Why has Jupiter's fourth-largest moon been one of NASA's highest priorities for so long?

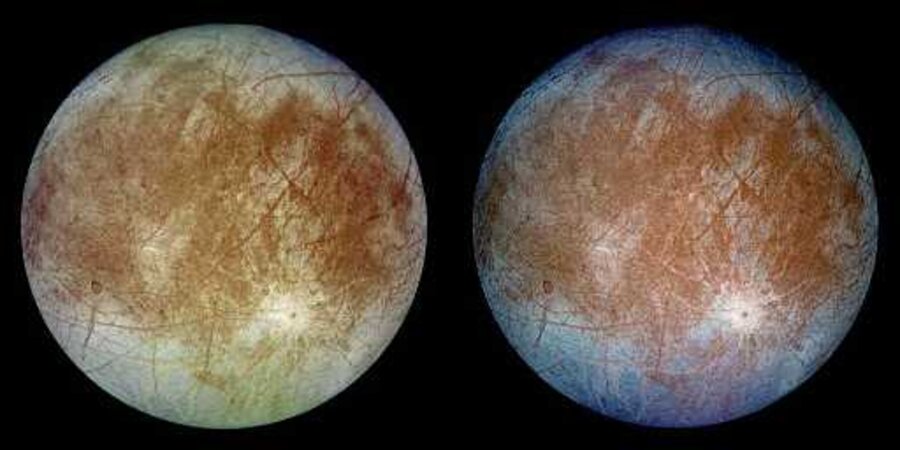

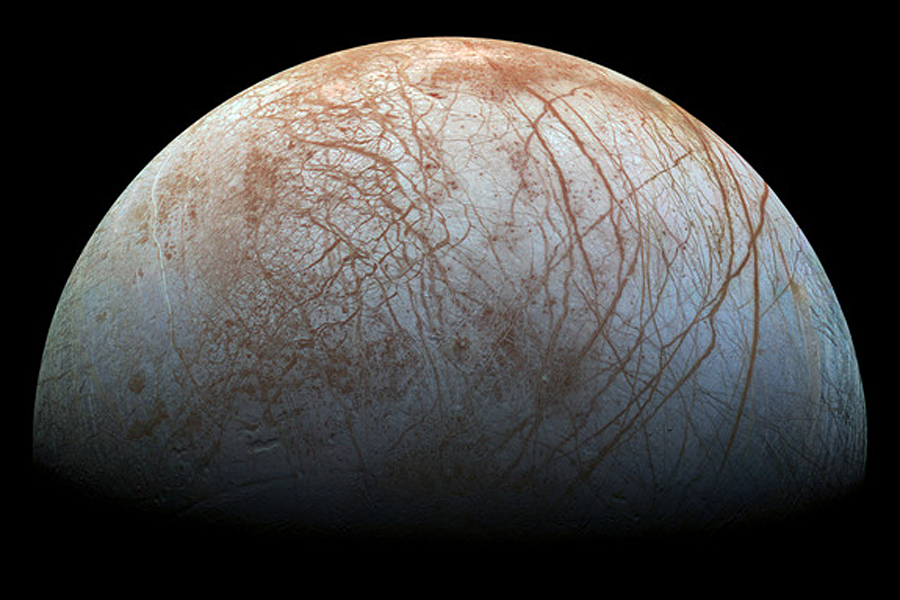

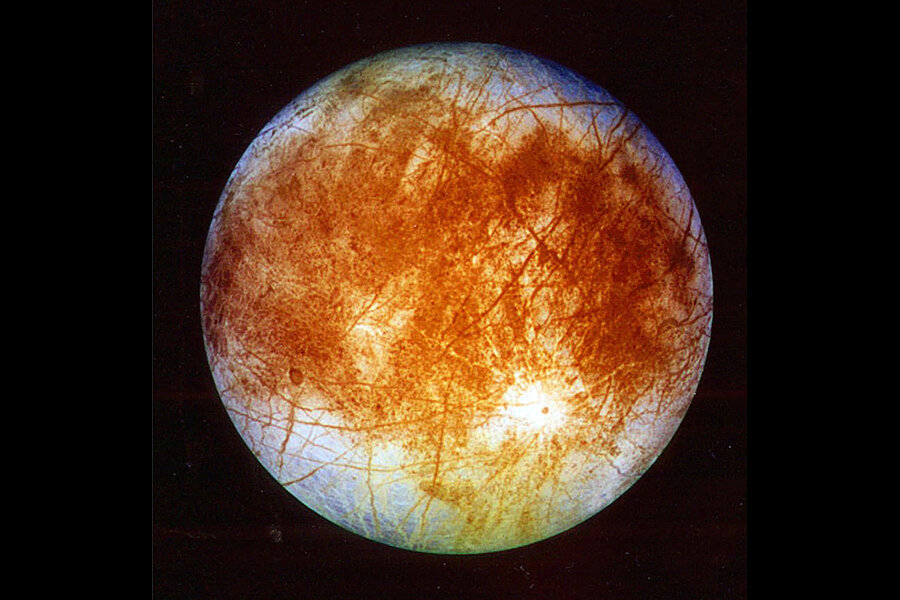

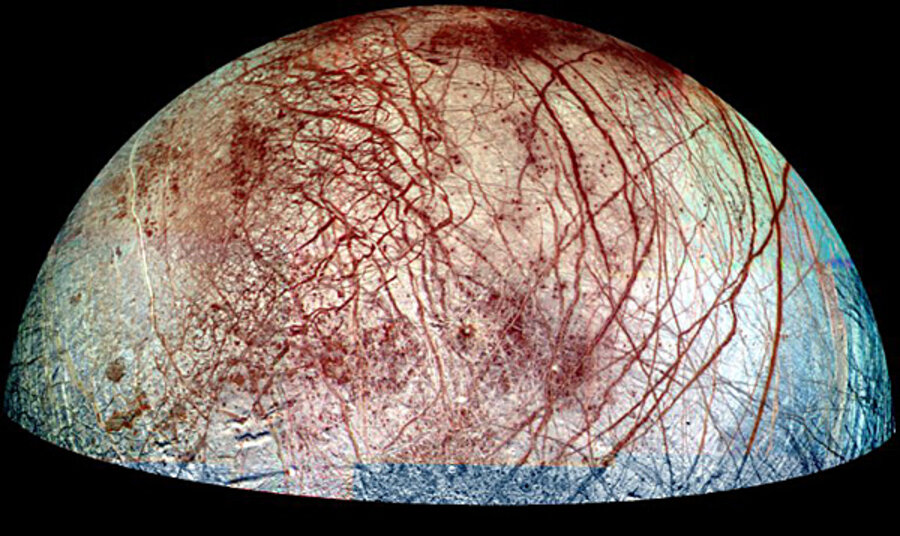

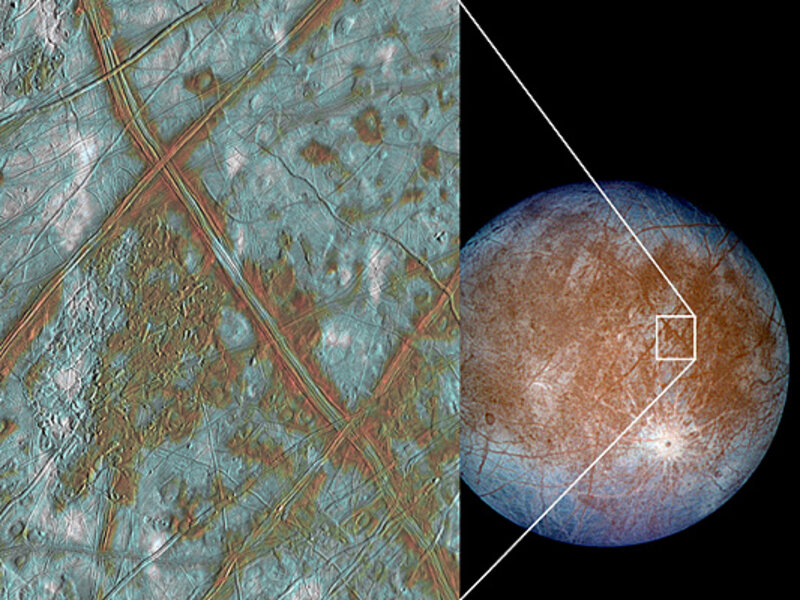

On the surface, Europa is a solid sphere of ice, interesting only because it is crisscrossed by reddish streaks. But beneath the frozen exterior, say NASA scientists, "is one of the most likely places to find current life beyond our Earth."

Data gathered from Earth-based telescopes and far-flung satellites have provided clues about Europa's interior, suggesting that, like a frozen lake, Europa holds liquid water beneath its icy surface. While it's not a unanimous opinion, it's certainly a tantalizing one.

"If we've learned anything about life on Earth, it's that where you find the liquid water, you generally find life," said NASA astrobiologist Kevin Hand. "So what if I told you that there is an ocean out there, beyond Earth? An ocean in our solar system, that has been in existence for billions of years?" According to scientists' models, it could encompass the planet, reach 10 times as deep as Earth's ocean, and hold two to three times as much water as all the liquid water on Earth.

"We used to think that in order for a world to be habitable, it had to be just at the right distance from the sun, or whatever your star was," says Dr. Hand, a researcher at NASA's Jet Propulsion Laboratory. "Here's where Europa is a real game changer. It is far, far out from the sun, and yet it's got this liquid-water ocean."

Why? "Because it's orbiting Jupiter, and the tidal tug and pull causes Europa to flex up and down, and all that tidal energy turns into mechanical energy, which turns into friction and heat that helps maintain this liquid-water ocean beneath an icy shell."

But life needs more than water. It also needs hydrogen, carbon, and an energy source. Europa has them all, says Hand. "Along with helping maintain liquid water, we think that tidal energy may also allow that ocean to interact with rocks on Europa's sea floor, and it may even give rise to things like hydrothermal vents, which could help provide not just the building blocks for life, but also the energy for life."

But so far, this is all just theory. To get confirmation, we need more data, in the form of a longer, more focused mission. NASA began soliciting mission design ideas last spring, highlighting the key science objectives outlined in NASA's Decadal Survey:

• Characterize the extent of the ocean and its relation to the deeper interior

• Characterize the icy shell and any subsurface water, and how they interact

• Determine the composition, formation history, and chemistry of Europa's surface

• Identify and characterize candidate sites for future detailed exploration

• Understand Europa’s space environment and interaction with the magnetosphere

Other missions, like Voyager and Cassini, have flown past Europa and Jupiter’s other moons, but they were each limited to a single, distant flyby. NASA’s Galileo spacecraft, launched in 1989, was the only mission that has yet made repeated visits to Europa, and it came close to the moon only a handful of times.

One proposed mission is the Europa Clipper, named for the speedy and lightweight 19th-century ships. Its instruments would include radar to penetrate the frozen crust and determine the thickness of the ice shell, an infrared spectrometer to investigate the composition of Europa's surface materials, a topographic camera for high-resolution imaging of surface features, and an ion and neutral mass spectrometer to analyze Europa's trace atmosphere during flybys.

"The question of whether or not life exists beyond earth, the question of whether or not biology works beyond our home planet, is one of humanity's oldest and yet unanswered questions," says Hand. "And for the first time in the history of humanity, we have the tools and technology and capability to potentially answer this question – and we know where to go to find it: Jupiter's ocean world, Europa."