Inside a Buddha statue, a surprise mummy

Loading...

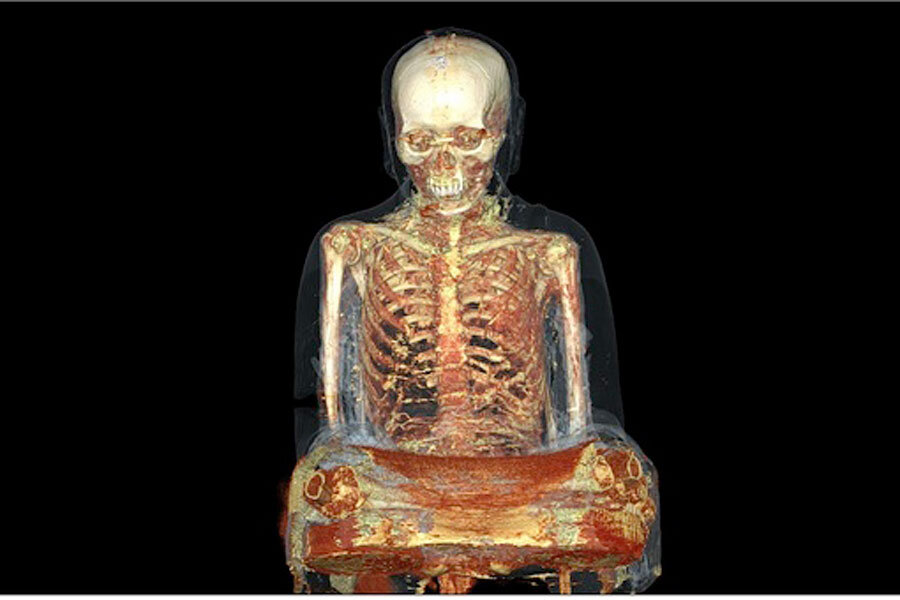

A Chinese statue of a sitting Buddha has revealed a hidden surprise: Inside, scientists found the mummified remains of a monk who lived nearly 1,000 years ago.

The mummy may have once been a respected Buddhist monk who, after death, was worshipped as an enlightened being, one who helped the living end their cycle of suffering and death, said Vincent van Vilsteren, an archaeology curator at the Drents Museum in the Netherlands, where the mummy (from inside the Buddha statue) was on exhibit last year.

The secret hidden in the gold-painted statue was first discovered when preservationists began restoring the statue many years ago. But the human remains weren't studied in detail until researchers took scans and samples of tissue from the mummy late last year.

The mysterious statue is now on display at the Hungarian Natural History Museum in Budapest. [Image Gallery: Inca Child Mummies]

Mysterious history

The papier-mâché statue, which has the dimensions, roughly, of a seated person and is covered in lacquer and gold paint, has a murky history. It was likely housed in a monastery in Southeastern China for centuries. It may have been smuggled from the country during the Cultural Revolution, a tumultuous period of social upheaval in Communist China starting in 1966 when Chairman Mao Zedong urged citizens to seize property, dismantle educational systems and attack "bourgeois" cultural institutions.

The statue was bought and sold again in the Netherlands, and in 1996, a private owner decided to have someone fix the chips and cracks that marred the gold-painted exterior. However, when the restorer removed the statue from its wooden platform, he noticed two pillows emblazoned with Chinese text placed beneath the statues' knees. When he removed the pillows, he discovered the human remains.

"He looked right into the bottom of this monk," van Vilsteren told Live Science. "You can see part of the bones and tissue of his skin."

The mummy was sitting on a rolled textile carpet covered in Chinese text.

Researchers then used radioactive isotopes of carbon to determine that the mummy likely lived during the 11th or 12th century, while the carpet was about 200 years older, van Vilsteren said. (Isotopes are variations of elements with different numbers of neutrons.)

In 2013, researchers conducted a CT scan of the mummy at Mannheim University Hospital in Germany, revealing the remains in unprecedented detail. In a follow-up scan at the Meander Medical Center in Amersfoort, Netherlands, the researchers discovered that what they thought was lung tissue actually consisted of tiny scraps of paper with Chinese text on them.

The text found with the mummy suggests he was once the high-status monk Liuquan, who may have been worshipped as a Buddha, or a teacher who helps to bring enlightenment after his death.

Last year, the mummy was on display at the "Mummies – Life Beyond Death" exhibit at the Drents Museum in Netherlands, before moving to the Hungarian Natural History Museum in Budapest.

Common practice

Mummies from this period are fairly common in Asia. For instance, researchers in Mongolia recently found a 200-year-old mummified monk still in the lotus position, the traditional cross-legged meditative pose.

It's not clear exactly how Liuquan became a mummy, but "in China, and also in Japan and Laos and Korea, there's a tradition of self-mummification," van Vilsteren said.

In some cases, aging Buddhist monks would slowly starve themselves to eliminate decay-promoting fat and liquid, while subsisting mainly on pine needles and resin to facilitate the mummification process, according to "Living Buddhas: The Self-Mummified Monks of Yamagata, Japan," (McFarland, 2010). Once these monks were near death, they would be buried alive with just a breathing tube to keep them holding on so they could meditate until death.

"There are historical records of some aging monks who have done this practice," van Vilsteren said. "But if this is also the case with this monk is not known."

Follow Tia Ghose on Twitterand Google+. Follow Live Science @livescience, Facebook & Google+.Originally published on Live Science.

- Photos: Ancient Egyptian Cemetery with 1 Million Mummies

- In Photos: An Ancient Buddhist Monastery

- 8 Grisly Archaeological Discoveries

Copyright 2015 LiveScience, a Purch company. All rights reserved. This material may not be published, broadcast, rewritten or redistributed.