Why Luke Skywalker's binary sunset may be real after all

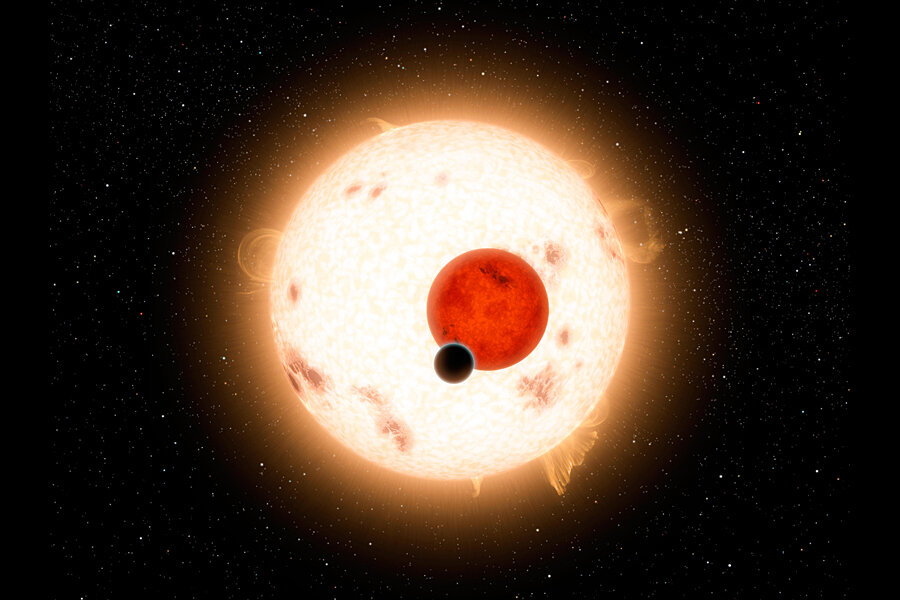

For all the sci-fi charm of watching a pair of suns sink below a distant horizon on a planet in a galaxy far, far away, conventional wisdom has held that binary-star systems can't host Earth-scale rocky planets.

As the two stars orbit each other like square-dance partners swinging arm in arm, regular variations in their gravitational tug would disrupt planet formation at the relatively close distances where rocky planets tend to appear.

Not so fast, say two astrophysicists. They argue that only are Tatooine-like planets likely to be out there. They could be as numerous as rocky planets orbiting single-star systems – which is to say, there could be large number of them.

Building rocky planets in a binary system not only is possible, it's "not even that hard," says Scott Kenyon, an astrophysicist at the Harvard-Smithsonian Center for Astrophysics in Cambridge, Mass., who along with University of Utah astrophysicist Benjamin Bromley performed the calculations.

Researchers have found Jupiter-scale gas giants orbiting binary stars and have estimated that such gas giants are likely to be as common in binary systems as they are in systems with a single star.

"If that's true, then Earth-like planets around binaries are just as common as Earth-like planets around single stars," Dr. Kenyon says. "If they're not common, that tells you something about how they form or how they interact with the star over billions of years."

The modeling study grew out of work the two researchers were undertaking to figure out how the dwarf planet Pluto and its largest moon Charon manage to share space with four smaller moons that orbit the two larger objects.

Pluto and Charon form a binary system that early in its history saw the two objects graze each other to generate a ring of dust that would become the additional moons.

The gravity the surrounding dust felt as Pluto and Charon swung about their shared center of mass would vary with clock-like precision.

Conventional wisdom held that this variable tug would trigger collisions at speeds too fast to allow the dust and larger chunks to merge into ever larger objects.

Kenyon and Dr. Bromley found that, in fact, the velocities would be smaller than people thought – no greater than the speeds would be around a single central object, where velocities are slow enough to allow the debris to bump gently and merge to build ever-larger objects.

They recognized that binary stars hosting planets are essentially scaled-up versions of the Pluto-Charon system. So they applied their calculations to a hypothetical binary star system with a circumstellar disk of dust and debris.

"The modest jostling in these orbits is the same modest jostling you'd get around a single star," Kenyon says, allowing rocky inner planets to form.

As for the Jupiter- or Neptune-scale planets found around binary stars, they would have formed farther out and migrated in over time, the researchers say, since there is too little material within the inner reaches of a circumstellar disk to build giant planets.

The duo's calculations imply that as more planets are discovered orbiting binary stars, a rising number of Tatooines will be among them.

Tatooine "was science fiction," Kenyon says. But "it's not so far from science reality."