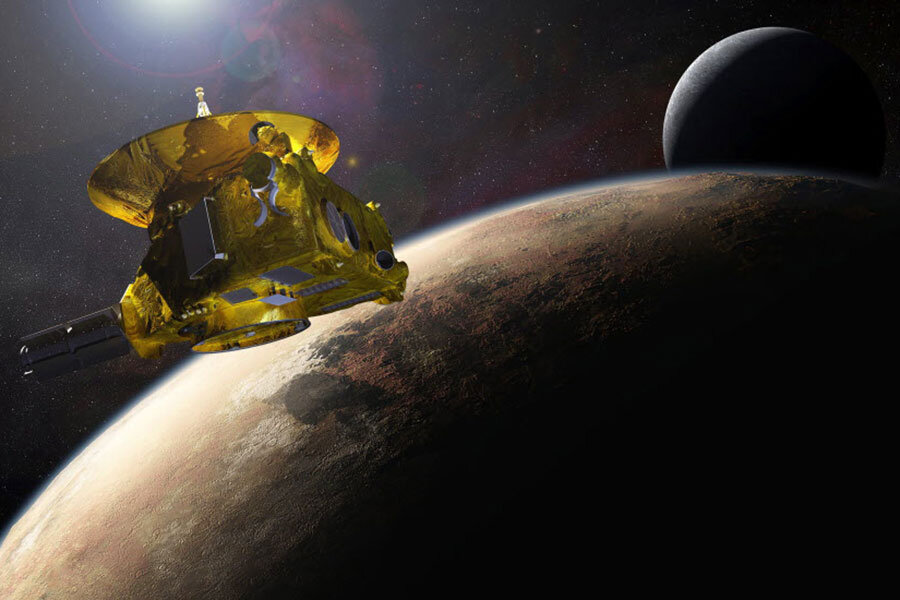

The lost 81 minutes. Is New Horizons spacecraft ready for Pluto flyby?

Loading...

Just 10 days before it was scheduled to give humanity its first-ever closeup view of Pluto, the New Horizons spacecraft went unexpectedly silent.

For 81 minutes on July 4, NASA lost control with its probe. When New Horizons started communicating again, it told mission control that it was in safe mode – in other words, it wasn't doing anything except keeping itself alive while waiting for new instructions from Earth, three billion miles away.

Scientists are trying to figure out what happened, and they must now essentially reboot the craft so it will be fully operational when it hurtles to within 7,800 miles of Pluto on the morning of July 14. It is a daunting task. Each command takes 8.8 hours to carry out – 4.4 hours to transmit to depths of the solar system and another 4.4 hours for New Horizons to transmit its answer back. The process could take days.

But the engineers furiously working to put things right have at least one small comfort: They were made for this.

Between the disappointments of lost spacecraft and the pride of textbook missions is the more-common reality of robotic spaceflight: Something often goes wrong, and NASA needs to pop the hood on a balky piece of machinery from millions of miles away. From Galileo similarly shutting down just hours before it was to make a flyby of Jupiter's volcanic moon, Io, to the Spirit rover temporarily becoming little more than an expensive Martian paperweight, space stuff breaks and – with remarkable ingenuity – NASA fixes it.

NASA engineers are currently trying to figure out what went wrong with New Horizons. But with communication reestablished, they are hopeful that the craft will be in fine working order well before July 14. Some preliminary imaging of Pluto and its moons Charon, Nix, and Hydra will be lost. But the team is not too worried about that.

"We may lose a few appetizers off the planned menu," mission participant Richard Binzel told Sky & Telescope, "but right now the focus is on delivering the main course."

On Thanksgiving Day 1999, "main course" took on an even more poignant meaning. Galileo went into safe mode just as engineers were cutting their turkeys and dipping into their mashed potato. In order to save the Io flyby, they had to manually retype and resend every command sequence – without a single error – so Galileo knew what to do. The original designers had expected the process of rebooting the spacecraft to take a month; the Thanksgiving Day engineers did it in fewer than six hours.

In 2004, just a few weeks after landing, the Spirit rover on Mars began spitting out only random bursts of data. Without any clue what was going on, engineers began to trace Spirit's unintelligible lines of code like bread crumbs, eventually discovering that Spirit sensed a problem with its flash drive and had unsuccessfully attempted to reboot itself more than 60 times to fix it. Within weeks, the rover was operational.

Indeed, rare is the mission that does not involve some sort of cosmic jerry-rigging. European Space Agency engineers are still working to establish reliable communications between Philae, which landed on a comet in November, and its mothership orbiting the comet. And even the NASA Curiosity rover, which perfectly executed the most thrilling and complicated landing in the history of robotic spaceflight, had a broken arm for several weeks.

As one Spirit engineer told the Monitor in 2004: "A perfect mission is great, but we engineers love jumping on stuff like this. It's exciting to figure it out and make the craft work again."