'Furry solar cells'? Lessons in solar power from space.

One of the greatest challenges with solar panels is, oddly enough, the sun. Or, more precisely, the problem is the angle that the sun’s rays shine on the panel.

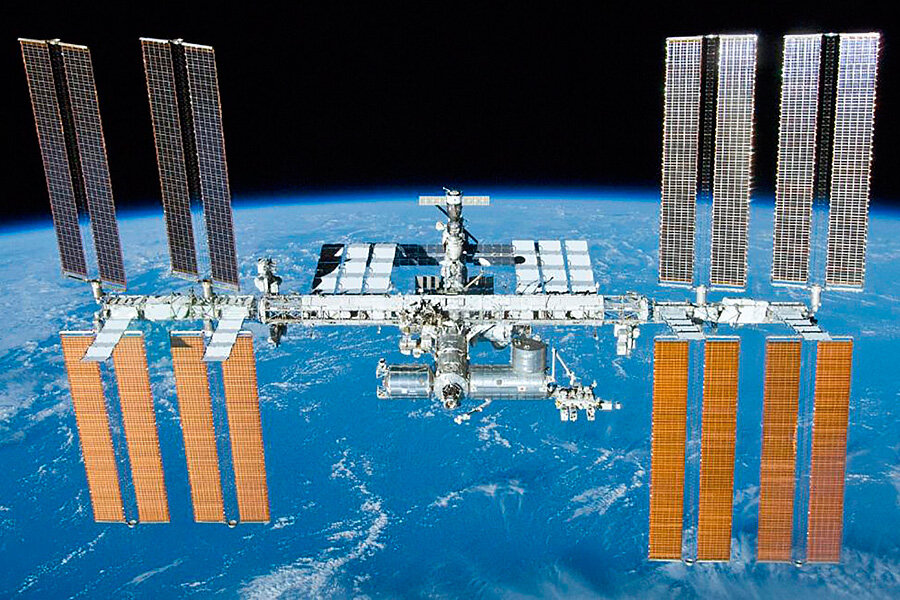

The International Space Station (ISS) fundamentally relies on solar power to fuel the station, which is currently collected by the dragonfly-like wings on the sides of the station. But these wings may soon be replaced by “furry solar cells,” says Jud Ready, an adjunct professor at Georgia Institute of Technology.

The ISS's solar panels currently follow the sun through a continuous rotating motion in order to maintain optimum light exposure, enabled by large bearings called “solar array alpha rotary joints.” In late 2007, one of the joints became very difficult to turn, forcing NASA to shut down the entire panel.

Now, these “furry solar cells” could eliminate the need for solar panel joints, resolving this problem, says Mr. Ready, speaking at the International Space Station Research & Development Conference in Boston on Thursday. These 3-D structures would have a coating on them that could capture light, without having to rotate with the sun.

His team has developed a photoabsorber made of copper, zinc, tin, and sulfur. "This unique material is supported on a scaffold of patterned & aligned carbon nanotubes towers that, when combined with a top contact made from transparent and conductive indium tin oxide, form a functional solar cell," says Ready in an email to The Christian Science Monitor. The coating also resolves the “thick-thin conundrum,” says Ready. This dilemma reflects the difficulty in having a coating that is thick enough to collect light, but simultaneously thin enough to extract the current efficiently. Ready and his team at Georgia Tech are working in conjunction with Bloo Solar, a company that works with 3-D solar technology in order to optimize efficiency and performance.

Solar cells have a history of causing difficulties in space, as challenges with panels have been chronicled back to 1982 on the MARECS-A communications satellite launched by the European Space Agency.

The new solar cell technologies have been set to launch on a couple of the past missions to space, but each of the missions carrying the panels has been unsuccessful. The cells fit easily into a CubeSat – a small, box-like “nanosatellite” that weighs close to three pounds.

But these solutions may be coming back to Earth, too. Ready says the teams are also, “commercializing the technology for terrestrial applications.”

Other companies have explored the use of 3-D technology for solar cells. “Our inspiration comes from fiber optics,” says Solar3D chief executive Jim Nelson in a 2011 interview with CNBC. “They manage the light to make it do what they want it to do, versus [flat] solar [panels] that just takes it as it comes.”

The 3-D cells were supposed to leave on the mission after the last SpaceX rocket that just exploded shortly after takeoff from Cape Canaveral Air Force Station on June 28. It is still uncertain when the cells will be placed on a mission to the ISS.