For scientists, should killing rare species be business as usual?

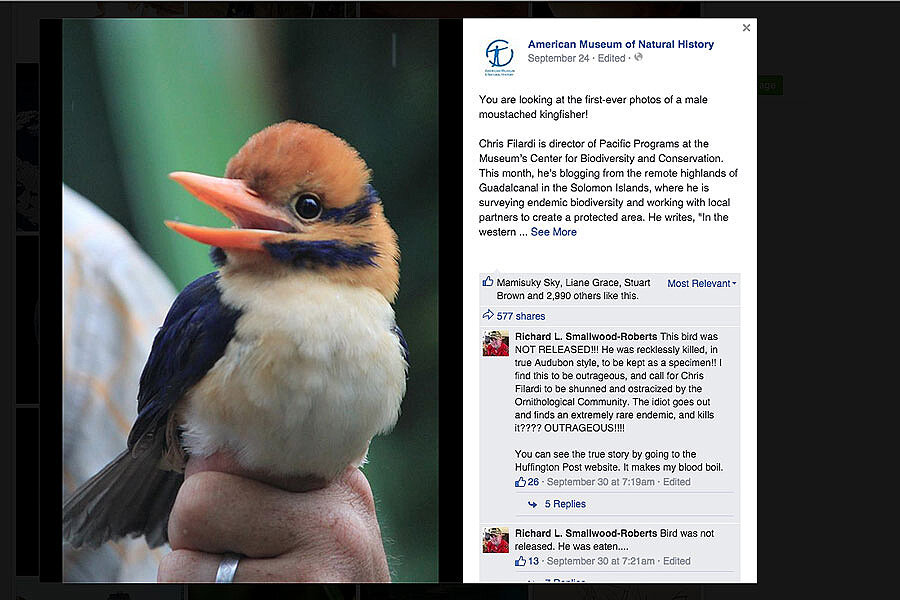

It’s a “ridiculously gorgeous rare bird.” It’s “adorable,” yet “cartoonish.” It was “gorgeous, strong, and raucous,” in the words of American Museum of Natural History biologist Chris Filardi, who found one in the highlands of Guadalcanal, Solomon Islands, last month, after it hid from scientists for more than half a century.

No one could say enough about the reappearance of the mustached kingfisher, Actenoides bougainvillei excelsus, especially after they learned that Dr. Filardi killed it.

“This was neither an easy decision nor one made in the spur of the moment,” Filardi wrote on Wednesday, confirming that his team had euthanized the mustached kingfisher, the only male ever found by scientists, after taking photographs and recording its song.

In his initial announcement of the finding, Filardi lavishly described his field site, the Guadalcanal hilltops painted as “sky island[s] filled with scientific mystery,” and wrote of his lifelong pursuit of “ghost animals,” species so rare that nothing can “fully shake the legend and mystery surrounding them.” His research focuses on biodiversity and conservation, trying to protect such creatures’ habitats for years to come.

Including the kingfisher:

When I came upon the netted bird in the cool shadowy light of the forest I gasped aloud, “Oh my god, the kingfisher.” One of the most poorly known birds in the world was there, in front of me, like a creature of myth come to life.

Only four kingfishers have ever been recorded, none male, and the last was captured in the 1950s. In light of this, and local communities’ reports that the bird is not uncommon – just rarely seen by visiting scientists – Filardi’s team felt the scientific cost of releasing the bird was greater than that of euthanizing it and taking it back to the lab for a flurry of tests, such as whether it is actually its own species.

Many weren’t buying the "kill to conserve" argument.

“Filardi’s weak justification attempts to explain why science trumps common sense, decensy, or morality,” protested Charlie Moores, a British bird-watcher and podcaster who founded Birders Against Wildlife Crime.

Another sarcastically commented that Filardi had best revise his description of the “creature of myth come to life” to “a mythical beast come to death.”

More substantiated criticism came from Professor Marc Bekoff, an expert on animal emotion, who, alongside conservation legend Jane Goodall, co-founded Ethologists for the Ethical Treatment of Animals.

Bekoff represents the new field of so-called compassionate conservation, which believes researchers must constantly keep in mind the welfare of not only humans and animal species, but individual creatures, as well.

“Far too much research and conservation biology is far too bloody and does not need to be,” Dr. Bekoff wrote in the Huffington Post. He has previously called out scientists who claimed their research demanded the deaths of wolves, barred owls, and a “puppy-sized spider.”

But scientists by the dozens are fighting back against the idea that occasional specimen-collecting equals harm, or even extinction. Over 120 signed a May 2014 letter to the editor of Science magazine in an attempt to discredit the notion that biologists collect samples indiscriminately. “Preserved specimens also provide verifiable data points for monitoring species health, distribution, and phenotypes through time,” they wrote, an argument Filardi pointed to when his critics attacked.

Just as historic eggshell collections helped convince the US to ban DDT, he wrote, we cannot totally predict the future use of specimens – but we can count on their being helpful. And the death of the mustache kingfisher also had immediate benefit, he argued: unprecedented steps are now in place to protect its environment.

The kingfisher may be in trouble, he admitted; but not because one died. Its environment may be threatened by climate change, which is not

the fault of some mining company or unscrupulous logger. These are threats from all of us who use petroleum and petro-chemicals, consume wood products, invest in extractive industry, or type on computers filled with metals dug from places rich in ore [like the Solomon Islands].