As climate changes, scientists call for unified, bigger view of tiny microbes

Loading...

To better understand how microbes affect the biosphere, three scientists (from the US, Germany, and China) proposed a Unified Microbiome Initiative (UMI) this week, in an effort to study the microbial community through a more holistic lens.

“Earth’s biome is not defined by national borders, and efforts to unlock its secrets should go global,” argue microbiologists Nicole Dubilier, Margaret McFall-Ngai, and Liping Zhao in Nature in the journal Nature Thursday. Scientists believe a better understanding of microbes will allow us to help key challenges in the 21st century, such as agriculture and environmental sustainability, because we are “only just realizing the full importance of the microbial world.”

So what are microbes?

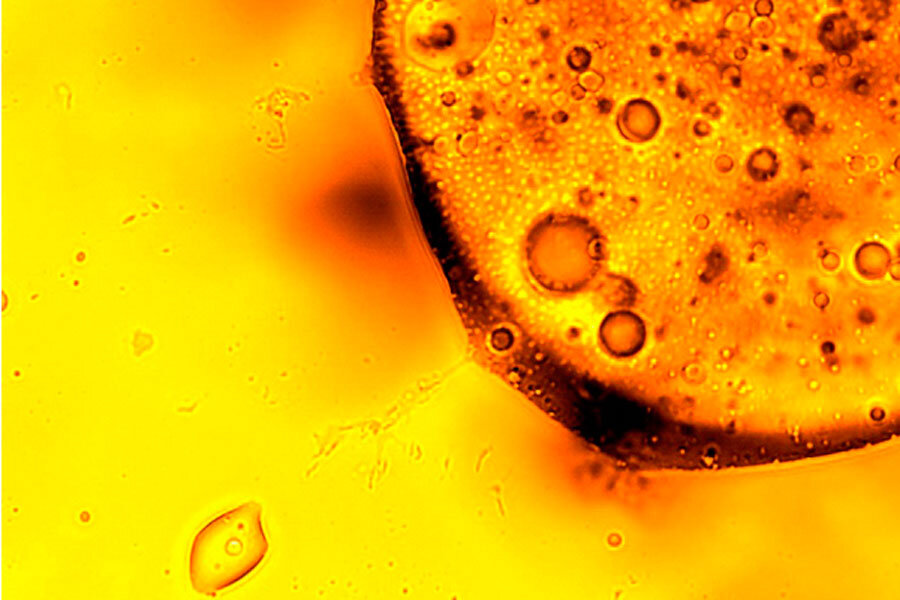

The Microbiology Society describes them as “very small living organisms, so small that most of them are invisible” and need a microscope to be seen. Scientists believe there are over 2-3 billion different microbe species, and they are divided into six different groups, including bacteria, fungi, algae and viruses.

“They make up more than 60 percent of the Earth’s living matter,” and they perform essential functions such as “breaking down dead plant and animal matter into simpler substances that are used at the beginning of the food chain,” the Microbiology Society explains.

The scientists behind the UMI, and a corresponding International Microbiome Initiative (IMI), say the world needs better coordination between microbiome researchers. UMI and IMI supporters say there needs to be easier ways to tackle data sharing and property rights between countries because scientists need to work together to advance microbe research.

“This lack of consistency in approaches means that effective comparisons and interpretations of human microbiota studies are often not possible,” but “the study of any micorbiome demands myriad collaborations,” say Dubilier, McFall-Ngai and Zhao.

The Director of the American Academy of Microbiology Ann Reid even suggested in 2011 that understanding and developing a microbe-plant partnership “could spark a new Green Revolution” that maximizes crop production naturally and efficiently.

Because of a changing climate and shrinking supply of arable land, “we need to develop crop plants that continue to be productive even when growth conditions are poor,” Dr. Reid argues. And if we could better understand the relationships between plants and microbes, we could learn how to make these relationships support further crop growth.

Recent research has shown that enhancement of microcrobial communities in agricultural land can improve drought tolerance of wheat, rice, and other staple crops – that's a promising development in the quest to eliminate hunger in an ever-warming and increasingly populated world.