Small animals thrive after mass extinctions, say scientists

Loading...

From blue whales to elephants, most of the world’s most massive species are facing extinction.

A new study of fish fossils suggests that when large vertebrates become extinct, evolution does not replace them for many years.

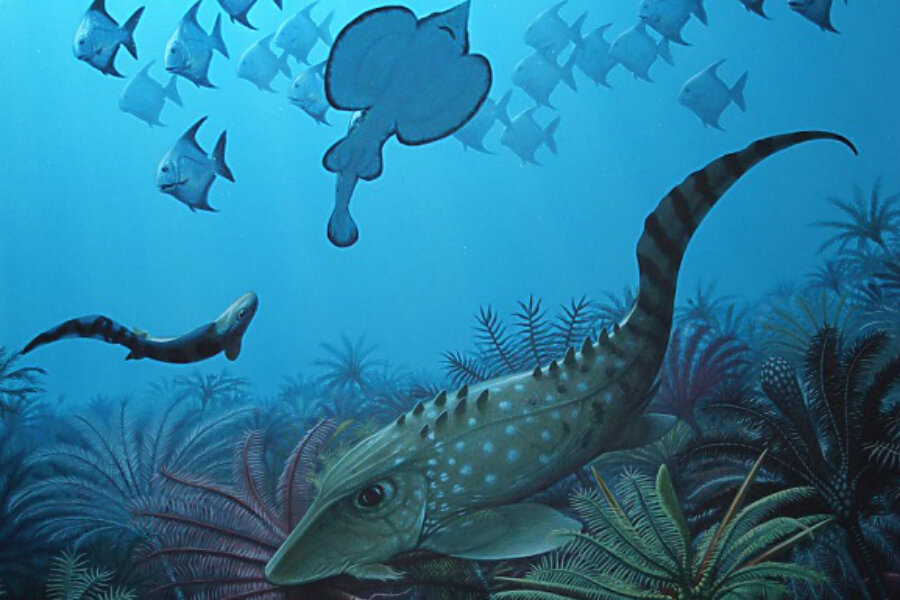

Researchers, after analyzing fish that lived about 350 million years ago, have concluded that a mass extinction known as the Hangenberg event caused large species to die off while smaller species survived.

"Rather than having this thriving ecosystem of large things, you may have one gigantic relict, but otherwise everything is the size of a sardine," said Lauren Sallan, an environmental scientist at the University of Pennsylvania, in a news release.

Her findings suggest that the smaller fish had a unique advantage over their larger counterparts: they breed much, much faster than their giant cousins.

"The end result is an ocean in which most sharks are less than a meter [three feet] and most fishes and tetrapods are less than 10 centimeters," or smaller than a grapefruit, said Dr. Sallen. "Yet these are the ancestors of everything that dominates from then on, including humans."

Paleontologists have long debated the changes in the body sizes of animals over time.

One theory, known as Cope's rule, says a species tends to enlarge over time to avoid predation and to become better hunters.

Another theory says that all things being equal, animals become larger in the presence of increased oxygen, or in colder climates.

Another idea, known as the Lilliput Effect, holds that after mass extinctions, there will inevitably be a temporary trend toward small body size. It’s named after a fictional island in the book “Gulliver’s Travels” that’s inhabited by tiny people.

Many scientists believe that we are on the brink of – if not in the midst of – a sixth mass extinction. This summer, scientists released a report indicating that humans are chiefly to blame for the mass extinction that is already underway.

But these same scientists say that aggressive conservation efforts may yet stave off a true mass extinction. Humpback whales, for example, were recently recommended for removal from the endangered species list.

"This will require rapid, greatly intensified efforts to conserve already threatened species and to alleviate pressures on their populations – notably habitat loss, overexploitation for economic gain, and climate change," wrote the research team, including scientists from Stanford, Princeton, and Berkeley, in their report.

If the present extinction does eliminate the planet's largest animals, the new study suggests they will not be replaced any time soon.

"It doesn't matter what is eliminating the large fish or what is making ecosystems unstable," Sallan said. "These disturbances are shifting natural selection so that smaller, faster-reproducing fish are more likely to keep going, and it could take a really long time to get those bigger fish back in any sizable way."