How do bats land upside down? Check out their heavy wings

Loading...

Of all known flying animals, bats have the heaviest wings in relation to their body weight, but that may not be so bad, according to scientists at Brown University. They recently found that, contrary to popular belief, this flying mammal actually derives some benefits from its wings' heft.

“We always tend to think of weight as a problem for anything that flies,” as more weight requires more energy to move it, says study lead Sharon M. Swartz to The Christian Science Monitor in a phone interview.

“Designers are always working on making things lighter,” she adds.

But in the case of at least two bat species, wrote Dr. Swartz and a team of researchers in Monday’s paper in the journal PLOS Biology, the often-overlooked role of inertia in bat flight is a critical force. By drawing in one of their heavy wings, bats use inertia to propel themselves into the acrobatic flips necessary to turn upside down for landing to roost.

This often happens in tight spaces like caves, researchers point out, so there’s little room for the aerodynamic forces typically triggered by flight speed to be the primary catalyst.

Inertia, Swartz explains, “is a less appreciated part of the movement repertoire of animals,” which includes ground reaction forces, hydrodynamic forces that help animals move through water, and aerodynamic forces that push them through air.

“It is a more subtle way to studying how animals and people move through the environment,” says Swartz, a bat researcher at the Aeromechanics and Evolutionary Morphology Lab at Brown.

Researchers discovered the role of inertia in bat flight by studying three Seba’s short-tailed bats (Carollia perspicillata) and two lesser dog-faced fruit bats (Cynopterus brachyotis) who were trained to fly into an enclosed space and land on a piece of mesh attached to the ceiling.

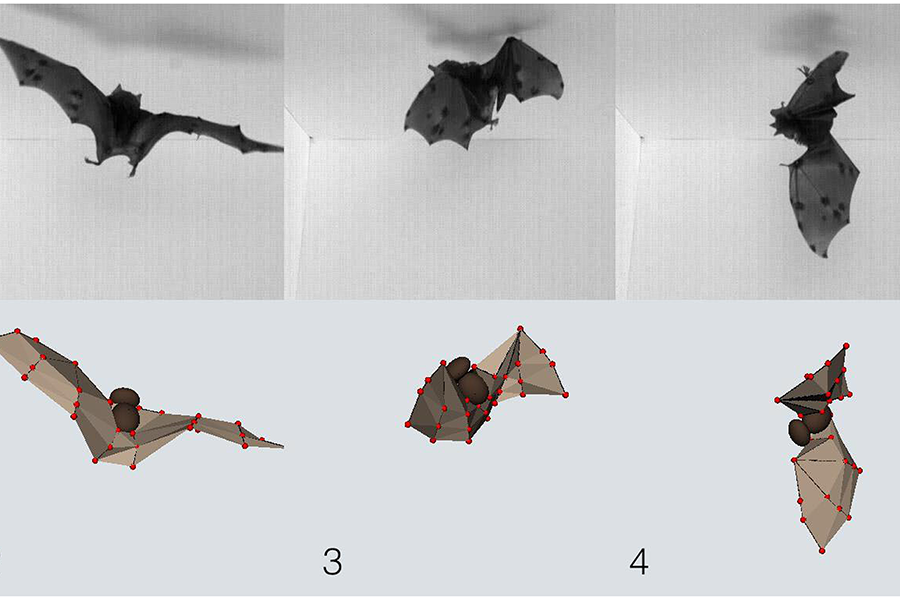

Three high-speed cameras captured the bats right before they landed. Videos show them shifting their weight to flip upside down by pulling one wing closer to their bodies while the other is extended.

This is the same force of inertia that figure skaters use when they pull their arms into their bodies to speed up their dizzying spins. It’s also what cats use when they twist their bodies to land on their feet.

Researchers also removed the mesh landing pad on the ceiling occasionally and found that as soon as the bats flipped over and realized there was nowhere to land, they quickly used the same technique to flip themselves back into flight mode.

This kind of response, she says, could inform flying technologies like drones. In fact, the lab is already working with collaborators at the University of Illinois on designs for flying bat robots, which will have soft, flappable wings. They could be used in homes of people with disabilities to pick things up, for instance, says Swartz.

“Because they’re soft, they don’t get hurt or hurt people,” if they crash, she explains.