Burping plasma: What happens when black holes gulp stars

Loading...

Black holes have always been elusive and mysterious. Scientists vouch for their existence, but much remains to be learned about them.

That's changing as astronomers have caught a rare glimpse of a black hole swallowing a star – providing fresh insights into how black holes digest stars: it involves what some describe as “burping.”

In the study, published Thursday in the journal Science, scientists determined that when a black hole eats a star, a tiny amount of star material gets released back out as a thermal flare.

The scientists tracked one particular star over the course of several months, using radio telescopes to make their observations. They watched as the star was first sucked in by a supermassive black hole, and then saw a fast-moving amount of plasma escaped from the black hole’s rim or event horizon. This disruption event was named ASASSN-14li.

"These events are extremely rare," Sjoert van Velzen, a Hubble fellow at Johns Hopkins and lead author of the study, said in a press release. "It's the first time we see everything from the stellar destruction followed by the launch of a conical outflow, also called a jet, and we watched it unfold over several months."

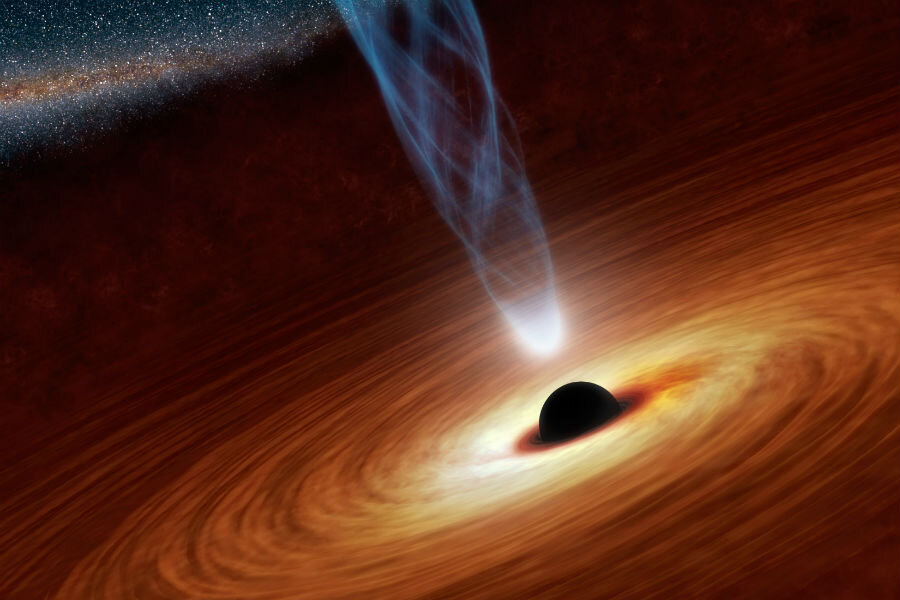

What makes these events even more unusual and exciting is that black holes are essentially invisible to humans due to their structure: Black holes are a very tightly packed collection of matter, formed from the remnants of very large dead stars. Because black holes have such high density relative to their area, they trap any and all light near them.

This makes it very difficult for scientists to observe them directly. One way scientists can figure out that a black hole is present is by observing how it interacts with surrounding stars and other interstellar material: black holes will usually suck up anything in their paths.

The team of scientists hunting down this particular black hole had to determine that the “burp” of plasma - elementary particles in a magnetic field - they’d found wasn’t from the black hole swallowing up something else, but was, in fact, from eating a star.

Their observations were correct, and they were then able to confirm their original hypothesis: “the tidal disruption of a star by a supermassive black hole leads to a short-lived thermal flare.”

"The destruction of a star by a black hole is beautifully complicated, and far from understood," van Velzen said in the release. "From our observations, we learn the streams of stellar debris can organize and make a jet rather quickly, which is valuable input for constructing a complete theory of these events."

The Johns Hopkins team was not the only team of scientists that had been observing the star. A second group of astronomers from Harvard had been making similar observations with radio telescopes, and had published their findings online. The two groups met for the first time at a workshop in Jerusalem in early November, when they presented their competing findings.

"The meeting was an intense, yet very productive exchange of ideas about this source," van Velzen said. "We still get along very well; I actually went for a long hike near the Dead Sea with the leader of the competing group."