How an MIT algorithm can make your selfies more memorable

Loading...

A tantalizing development at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology could help boost the popularity ratings of selfie takers and online daters.

Scientists at the institute’s Computer Science and Artificial Intelligence Laboratory (CSAIL) have taught computers to predict, with near perfect precision, which photos of faces, nature scenes, or other objects people are most likely to remember.

Though similar predictive algorithms in the field of machine learning already allow computers to predict information by automatically completing phrases people type into Google search or by recognizing people to tag in photos on Facebook, scientists have not until now been able to use these tools to teach computers to predict what will be memorable to people, a skill that even humans themselves lack, Aditya Khosla, a PhD student in computer science at MIT, told The Christian Science Monitor.

For selfies and other portraits, this development means an app might one day tell people which one from a group of photos is likely to get the most likes on Instagram, or to attract more suitors on a dating site. The team in 2013 developed an algorithm that can slightly modify pictures of faces to give them a more memorable flair.

“While deep-learning has propelled much progress in object recognition and scene understanding, predicting human memory has often been viewed as a higher-level cognitive process that computer scientists will never be able to tackle,” said CSAIL principal research scientist Aude Oliva in an announcement.

“Well, we can, and we did!” said Dr. Oliva, a co-author of a paper on the topic with Mr. Khosla and other MIT researchers that was presented this week at the International Conference on Computer Vision in Chile.

To test its new algorithm, the CSAIL team hired 5,000 people from across the globe through a crowdsourcing site called Mechanical Turk, an Amazon company the connects developers with millions of people who are willing to perform simple tasks for small payments.

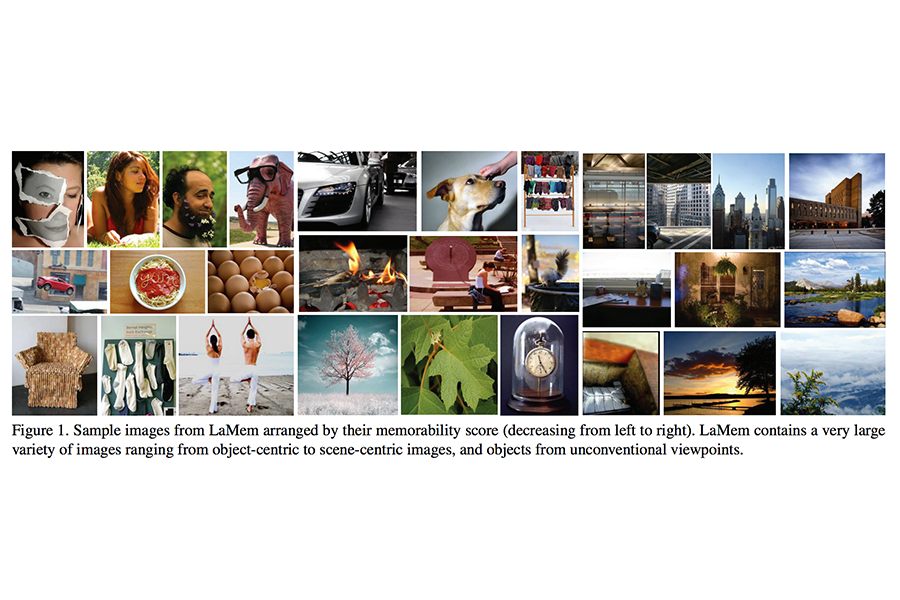

The scientists showed their workers hundreds of images, each one for 600 milliseconds, and recorded which ones were memorable, meaning that people were able to identify the image after seeing it once. Then they presented the same images to their algorithm to see if it could identify the ones that were memorable to their human subjects.

“We told it, ‘These images are more memorable, these are less,’ go figure out why,” explains Khosla.

It turned out the algorithm was really good at finding patterns among disparate images, ones that included faces, nature, abstract scenes, and so on. It was 30 percent better than any others algorithms out there, the authors say.

What the algorithm can’t do is explain the mysterious ways in which it finds patterns that shape memorability, says Khosla.

“The algorithm is able to figure out the patterns that influence what makes an image memorable or forgettable,” he explains. “But it’s very hard for us to distill the knowledge that the network learned.”

There’s been other research exploring what features make images stand out: people are better than landscapes, negative emotions appear to be more resonant than positive ones, for instance. The CSAIL team in 2014 explored image popularity by asking its algorithm to analyze 2.3 million pictures from photo-sharing site Flickr to determine what makes them more or less popular on social media.

Some of the results were unsurprising: Among the most popular subjects in images, the team found, were revolvers and women in bikinis. The unpopular ones were spatulas, plungers, and laptops. Bright, indoor colors drew more attention on social sites.

The image popularity and memorability work has applications beyond improving people’s social media rankings, though. Khosla says it could be used to improve the salience of advertising images and of those used in education.

“Right now, you just take a random image and display that in text books,” says Khosla.”If we started picking content that’s much more memorable, it might make it easier for students to remember these things.”