As storms pound drought-stricken California, what is El Niño anyway?

Loading...

Forecasters have predicted rain over parched California over the next two weeks, thanks to El Niño storms.

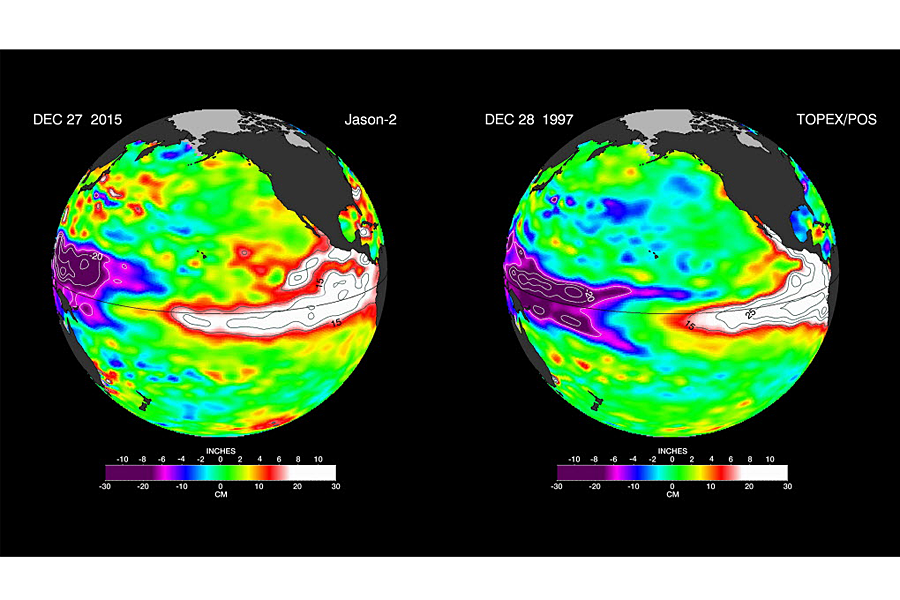

The El Niño effect brings warmer ocean temperatures and increased rainfall to the West coast of the Americas for many months. These episodes can be irregular, occurring every two to seven years for nine to 12 months, sometimes stretching on for years.

So what drives these shifting weather patterns across the Pacific Ocean?

Globally, ocean temperatures influence precipitation. Over warmer sections of the ocean, more clouds form and more rain falls in that region.

Especially near the equator, the sun heats up sea surface temperatures. Most of the time, the Pacific trade winds push that warm water away from Central and South America toward Indonesia. Cold water from the depths of the ocean rises into that warm water's place, bringing drier weather to the Americas.

But when that wind weakens or changes direction, usually in the fall or winter, the water along the west coast of the Americas gets warmer again. That is El Niño.

El Niño has a counterpart, La Niña. Together, they form the El Niño-Southern Oscillation, or ENSO. El Niño is the warm phase, while La Niña appears as its cold opposite.

The current El Niño is predicted to soak the west coast, bringing hope of relief from the region's four-year drought.

Bill Patzert, climatologist with NASA’s Jet Propulsion Laboratory in La Cañada Flintridge, Calif., told the Los Angeles Times, “I’m quite optimistic that the entire state is going to get hosed."

But such a downpour could shock the parched California dirt, leading to mudslides and flooding. And Dr. Patzert says it's unlikely that El Niño will deliver enough of a punch to knock out California's drought.

"Over a 25-year period, over the long term, El Niño provides only 7% of our water. So as much as we’re hyping it, it’s not a big player," Patzert said. "It’s fast and furious, but it’s too irregular – the gap between El Niños is too long to build any statues to El Niño to be a drought-buster."

Still, any rain will bring some relief, as groundwater, reservoirs, and snowpack are dwindling.

El Niño was named by South American fishermen in the 1600s. When unusually warm water appeared where they were fishing in the ocean, they noticed many of the fish disappear or move. The name means The Little Boy or Christ Child, in Spanish, named for proximity to Christmas.