Temperatures rising: How humanity's heat output affecting our oceans

Loading...

The amount of heat energy produced by humans and absorbed by ocean waters has doubled since 1997, according to a study published in Nature Climate Change Monday.

The study includes data collected from the 1860s to the present day, and finds that the amount of energy the world’s oceans took in from 1865 to 1997 is about equal to the amount absorbed from 1997 to 2015.

The energy soaked up throughout the first 132 years tracked in the study totaled about 150 zettajoules (ZJ), or 150 sextillion joules. The last 18 years also saw a total of about 150 ZJ absorbed by the oceans. It is estimated that the world’s total annual energy consumption is around 0.57 ZJ, according to the International Energy Agency.

"The changes we're talking about, they are really, really big numbers," Paul Durack, the study’s co-author and a research scientist at the Lawrence Livermore National Laboratory, told the Associated Press.

"They are nonhuman numbers," he said.

The data used for the earlier years comes from the HMS Challenger, a scientifically-outfitted British warship that was in commission until 1878. The analysis also takes into account several more recent measurements and, using a multi-model mean, proposes the recent ocean heat content (OHC) increases.

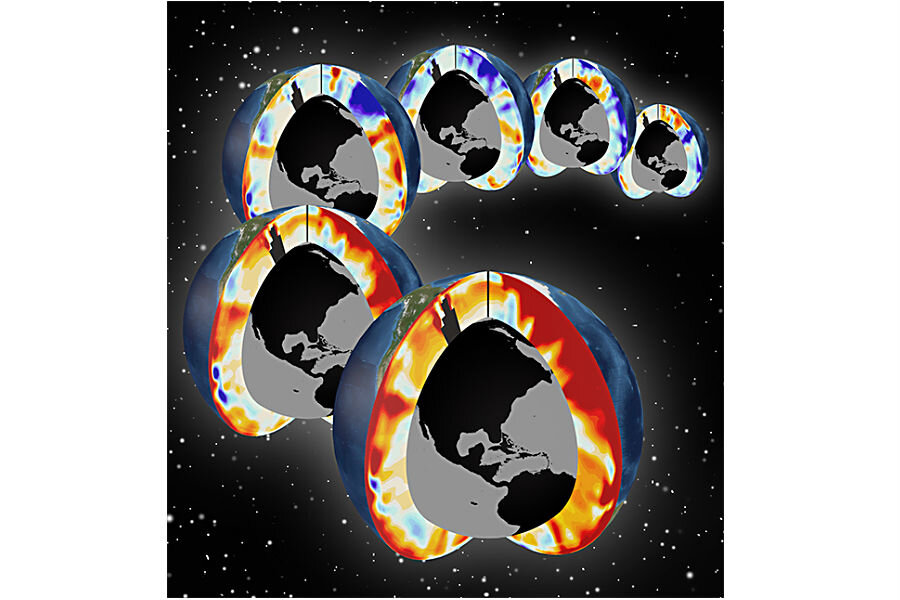

The majority of the changes have come at ocean depths up to 700 meters, while slightly more than one third occurred at depths ranging from 700 meters to the ocean floor. As water closer to the surface continues to warm, it loses its ability to absorb heat from land and air.

"These finding have potentially serious consequences for life in the oceans as well as for patterns of ocean circulation, storm tracks, and storm intensity," said Oregon State University professor and Marine Studies adviser Jane Lubchenco to the AP.

While the heat energy capture means that the oceans are only warming by tenths of degrees, the increases are happening at a much higher rate than in the past – especially since the start of the new millennium. That, in addition to the excess heat in the ground and the air, could cause a more rapid increase in global warming in the coming years as energy is trapped in the climate system at a higher rate.

And even though the study already portrays a dramatic increase in OHC levels, some climate analysts such as National Center for Atmospheric Research senior scientist Kevin Trenberth suggest that the study “significantly underestimates” OHC changes, according to the AP.

Studying OHC shifts is not the definitive way to measure warming and its effects on worldwide climate change. But the clear rapid increase in the percentage change in OHC points to some connection between the heat energy output by human industry, especially beginning around 1920, and global ocean temperatures.

Scripps Institution of Oceanography geosciences professor Jeff Severinghaus told the AP that the study shows “real, hard evidence that humans are dramatically heating the planet.”