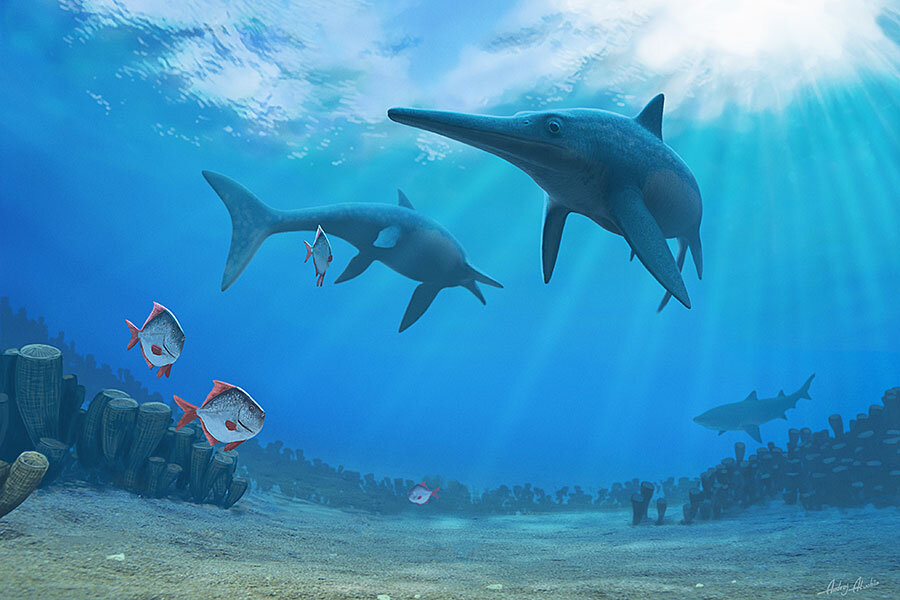

'Sea dragon' reveals glimpse of fleeting prehistoric world

New research delving into the world of the ichthyosaur, or ‘sea dragon,’ has uncovered new details about its extinction.

The work, published Tuesday in Nature Communications, reexamines the factors that led to this marine reptile's demise roughly 30 million years prior to the mass extinction that killed off the dinosaurs.

Researchers describe a bizarre marine world that spun into existence for a mere geological blink of an eye.

“Speculation has clouded the severity and timing of [the ichthyosaurs’] extinction, which was first assumed to occur at the end of the Cretaceous,” say the authors in their paper. “Subsequent analysis placed this extinction at the end of the Cenomanian; ichthyosaurs thus disappeared after a 157-million-year reign, 28 million years before the end-Cretaceous extinction events that marked the demise of other numerous marine taxa.”

Until now, most scientists accepted that ichthyosaurs went extinct because diversity among this group of marine predators was low.

Under such circumstances, relatively minor changes alone could have wiped them out, such as “increased competition with other marine reptiles” or “a diversity drop in their assumed principal food resource, belemnites” (ancient cousins to squids and octopuses).

But closer examination of the fossil record paints a different picture, say Dr. Valentin Fischer, of the Universities of Liège and Oxford, and his colleagues.

“We analyzed the extinction of this crucial marine group thoroughly for the first time,” said Dr. Fischer in a press release. “Ichthyosaurs were actually well diversified during the last chapter of their reign, with several species, body shapes, and ecological niches present.”

In addition, no other large marine reptiles existed to outcompete them – the only comparable creatures didn't grow into keystone predators until after the ichthyosaurs were long gone, say the researchers.

The key to their demise was a slow rate of evolution, they argue. Before their extinction, ichthyosaur species were highly diverse, both in terms of body shape and ecological niche. But after an extinction event in the early Cenomanian period killed off many ichthyosaur species, the days of the rest were numbered.

"The extinction of ichthyosaurs did not happen in an ecological vacuum," as previous work had suggested, argue Fischer and his colleagues.

Instead, they found "evidence for profound global environmental volatility within the Cenomanian, [including] sea level fall and perturbations of geochemical cycles.”

Prior to these dramatic changes, Earth had no polar ice, sea levels were extremely high, and temperatures as high as Earth has ever seen, to mention just some of the peculiarities of the period.

Then came the changes that rocked the whole marine ecosystem, straining the species roaming the world’s oceans. For some, including the ichthyosaur species that had survived the first blow, it was all too much.

“Although the rising temperatures and sea levels evidenced in rock records throughout the world may not directly have affected ichthyosaurs,” said Fischer, “related factors such as changes in food availability, migratory routes, competitors, and birthing places are all potential drivers, probably occurring in conjunction to drive ichthyosaurs to extinction.”

Fischer and his colleagues aren't done investigating this enormous shift in the marine environment.

Our findings support "a growing body of evidence revealing that a major, global change-driven turnover profoundly reorganized marine ecosystems during the Cenomanian," write the authors, "to give rise to the highly peculiar and geologically brief Late Cretaceous marine world."