Do solar 'superflares' pose a danger to Earth?

A large enough flare from the Sun could pose a threat to Earth, a new study finds.

Led by Aarhus University scientists, an international team of researchers examined the possibility of the Sun releasing a superflare – a massive explosion on the solar surface up to 10,000 times more powerful than the strongest flares ever observed. The paper appeared in Nature Communications.

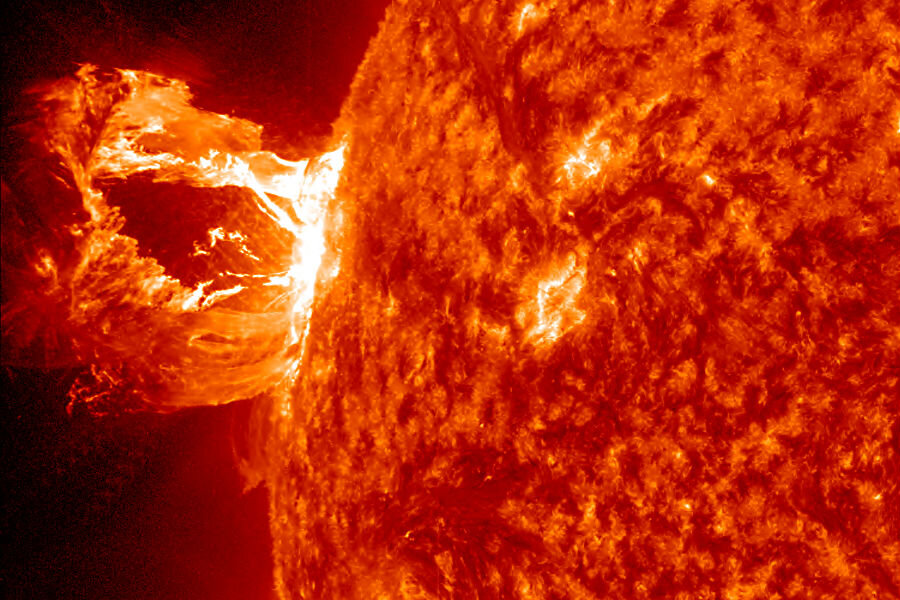

Superflares have been observed only on other stars, but solar flares resulting from magnetic field collapses on the sun are not uncommon, and clouds of charged particles from those interactions have reached Earth in the past. Solar flares are known to cause technology disruptions, but do not typically impact terrestrial life in a major way.

If our sun were to put out a superflare, however, the effects could be far worse. Scientists are unsure of the exact causes behind superflares on other stars, but if one were to occur in the solar system, Earth’s satellites could be knocked out, and its electric grids could go dark. Even the Earth's protective ozone layer could be damaged.

The largest known solar flare to hit Earth, called the Carrington Event, happened in 1859 when limited technological infrastructure was in place around the world. That storm’s power could not be precisely recorded at the time, but its effects were. A bright aurora was seen at different posts around the world, telegraph lines began operating erratically, and evidence of ozone layer damage at the time has been found through ice records in Greenland.

It has been suggested that the Carrington Event could have been the first recorded superflare from the Sun, although it may have simply been a large solar flare. Either way, if an event of that magnitude occurred today it would have a much larger impact around the globe than it would have in the 19th century.

Evidence of potentially similar events in 775 and 993 were also found through the examination of radioactive isotopes in Japanese tree rings, although their connection to superflares has not been not confirmed.

The team of scientists aimed to find out whether the Sun is actually capable of such a massive event, and what the likelihood of it striking Earth might be. They went about the study by analyzing stars – including ones similar to our sun – to determine if there is a link between the origin of solar flares and superflares, and to see if stars similar to the sun put out superflares.

Using stellar data taken from the Large Sky Area Multi-Object Fibre Spectroscopic Telescope (LAMOST) in China, the researchers were able to show that stars emitting superflares generally have “larger chromospheric emissions” than other stellar bodies in the range of the Sun.

“The magnetic fields on the surface of stars with superflares are generally stronger than the magnetic fields on the surface of the Sun,” researcher and Aarhus associate professor Christoffer Karoff, one of the study’s authors, said in a university release. “This is exactly what we would expect, if superflares are formed in the same way as solar flares.”

While this cuts down on the likelihood of a true superflare ever occurring in the solar system, the scientists noted that flares coming from stars on the same scale and activity level as the sun do sometimes happen. This suggests a link between the causes of solar flares and superflares, and that a superflare from the Sun could happen.

“We certainly did not expect to find superflare stars with magnetic fields as weak as the magnetic fields on the Sun,” Mr. Karoff said. “This opens the possibility that the Sun could generate a superflare – a very frightening thought.”