'Computer vision' brings Martian surface into stunning relief

Loading...

The idea of enhancing an image digitally to reveal previously unseen levels of detail has become something of a sci-fi movie cliché. Now, astronomers at University College London have used a similar computer vision technique to learn more about the location of the missing Beagle 2 probe on the surface of Mars.

A paper on the novel "stacking and matching" technique, which allows researchers to pick out objects at a resolution of up to five times greater than the original images, was published in the journal Planetary and Space Science in February.

But just recently, the UCL researchers began using the technique, called Super-Resolution Restoration (SRR), to identify individual objects on the red planet's surface.

"We now have the equivalent of drone-eye vision anywhere on the surface of Mars where there are enough clear repeat pictures," Jan-Peter Muller of UCL's Mullard Space Science Laboratory says in a press release. "It allows us to see objects in much sharper focus from orbit than ever before and the picture quality is comparable to that obtained from landers."

In addition to revealing more about past missions, the technique could help identify safe landing spots for future rovers and explore vast expanses that wouldn't be possible to cover with a land-based probe, he says.

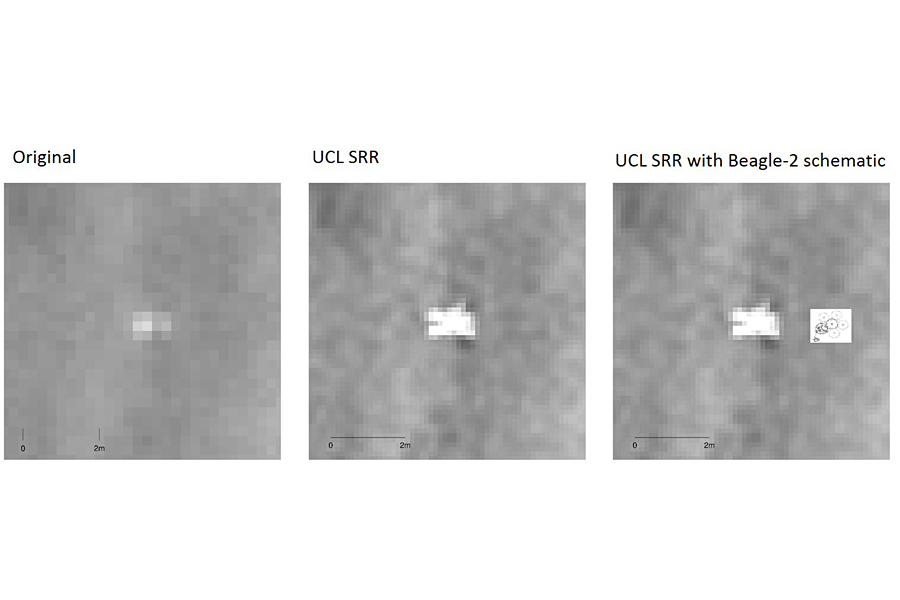

The new picture, which is four times the resolution of previously available images, shows a bright blip on a dusty surface. It lends credence to the theory that the European Space Agency's diminutive probe, which was previously believed to be lost, may have landed as planned on Mars in 2003 but failed to fully unfurl its solar panels.

"Given the size of Beagle 2, even with super-resolution images you are not likely to see more than a series of blobs because it is so small," Mark Sims, a professor of astrobiology and space instrumentation at Britain's University of Leicester and former mission manager for Beagle 2, told the Guardian.

"What it does show is that it is on the surface and it is at least partially deployed," added Dr. Sims, who released an image last year from NASA's High Resolution Image Science Experiment (HiRISE) that showed three specks thought to be Beagle 2, its parachute, and rear cover.

The UCL researchers then digitally enhanced that image by stacking and fitting together as many as eight HiRISE images of the same area taken from different angles, Dr. Muller told the Guardian.

The technique greatly improves on the resolution available with the largest telescopes that can be launched into orbit. Currently, that is limited to around 25 cm (about 10 inches) for a telescope orbiting Earth and Mars.

The SRR technique, by contrast, allows astronomers to examine objects as small as 5 cm (about 2 inches) using the same 25 cm telescope. Unlike the sci-fi version, however, it's still a lengthy, computationally intensive process.

Enhancing a small scene of 2,000 by 1,000 pixels takes three days on the lab's fastest computers, Dr. Muller told the Guardian, noting that they couldn't yet analyze an entire scene.

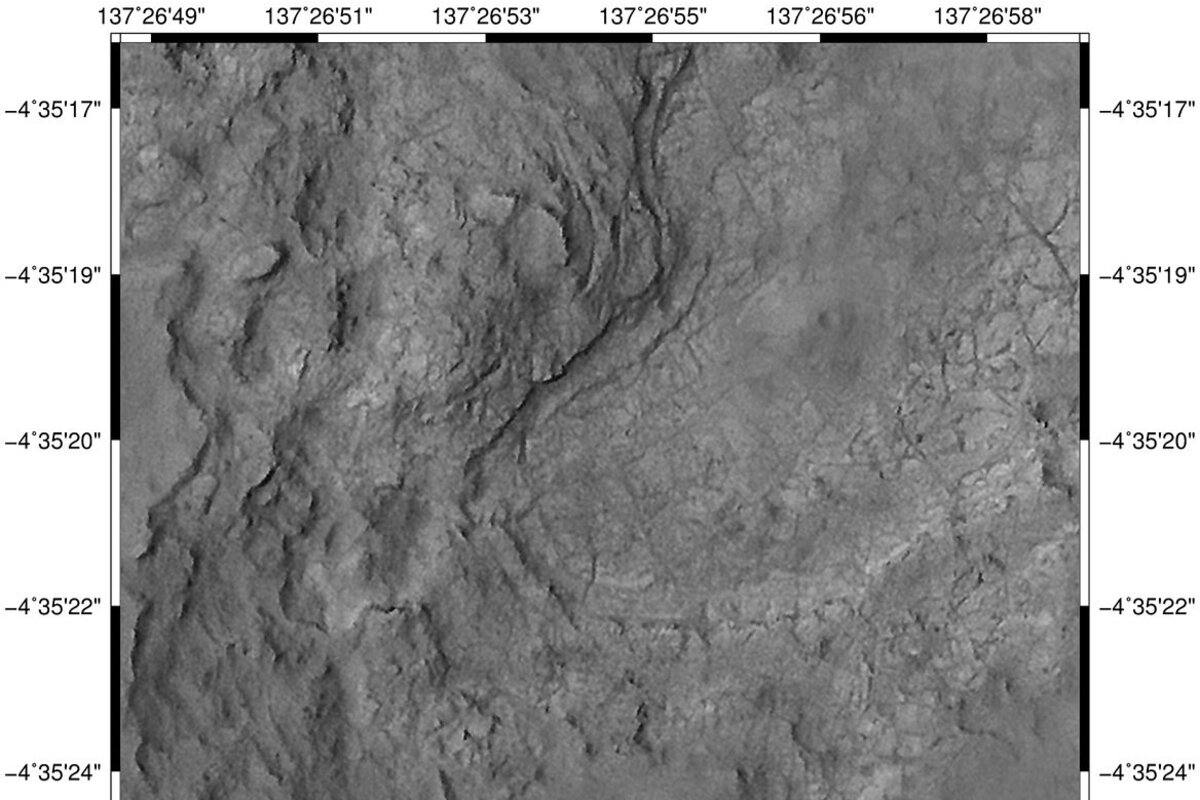

They also released enhanced images that show Mars' ancient beds in much sharper detail. One image even reveals tracks from NASA's Spirit rover. Next, they plan to explore other areas of Mars using the "super-resolution" images.

"This technique has huge potential to improve our knowledge of a planet's surface from multiple remotely sensed images," Yu Tao, a UCL research associate who co-authored the paper, said in the release. "In the future, we will be able to recreate rover-scale images anywhere on the surface of Mars and other planets from repeat image stacks."