Evidence of humongous asteroid unearthed in Australia

Loading...

Scientists have unearthed evidence of one of the largest asteroids ever to assail the Earth.

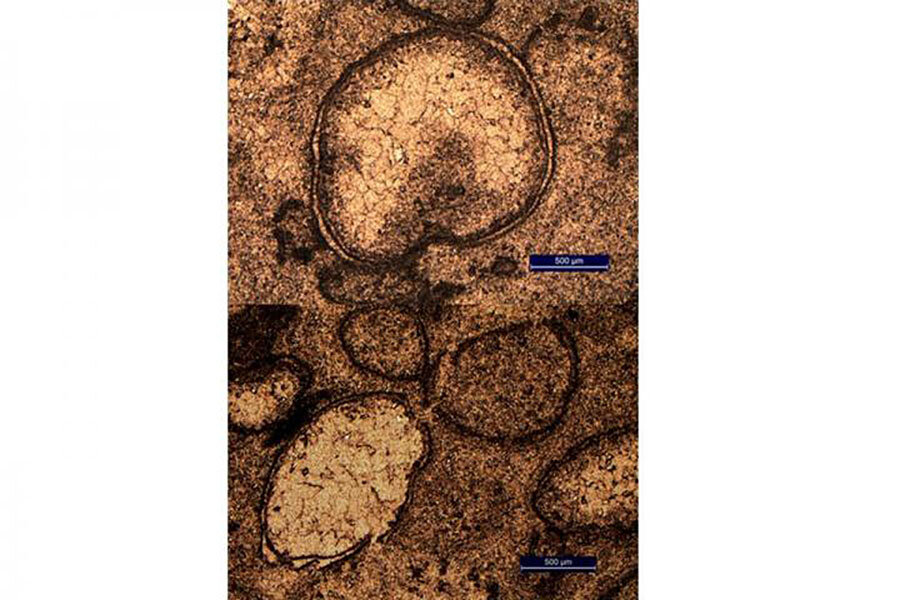

Delving into some of the oldest known sediments on the planet, researchers in northwestern Australia discovered a trove of tiny glass beads known as spherules, vaporized remnants of an asteroid slamming into the surface.

The research, to be published July 2016 in the journal Precambrian Research, details an impact more powerful than any yet experienced by mankind.

"The impact would have triggered earthquakes orders of magnitude greater than terrestrial earthquakes, it would have caused huge tsunamis and would have made cliffs crumble," said lead author Andrew Glikson from The Australian National University (ANU).

The location of the crash site is hard to discern, as material from the asteroid would have spread to every corner of the globe. Moreover, in the billions of years that have since marched by, volcanic activity and the journeys of tectonic plates would have obliterated any remnants of a crater.

Yet that crater, according to Dr. Glikson, an Earth and paleoclimate scientist, would have stretched for hundreds of miles, carved out by an asteroid of epic proportions – up to 18 miles in diameter.

It is, in fact, the second oldest asteroid known to have struck our planet. The glass spherules emerged from seafloor sediments dating to 3.46 billion years ago.

"This is just the tip of the iceberg. We've only found evidence for 17 impacts older than 2.5 billion years, but there could have been hundreds," Glikson said in an ANU press release.

Indeed, not long – relatively speaking – before this asteroid crashed into Earth, the moon was pummeled by an avalanche of such events, about 3.8 billion to 3.9 billion years ago. It was this sustained assault that gave our satellite its characteristic craters, known as maria, still visibly scarring its surface.

The glass spherules hinting at this particular impact were unearthed in a place called Marble Bar, preserved in a sediment layer that had originally lain at the bottom of the ocean. The geological time capsule was sandwiched between two volcanic layers, which in turn allowed the scientists to date it with such precision.

Far from being Glikson's first foray into the arena of ancient impacts, he has been scouring the Earth's surface in search of such things for 20 years. So when the glass spherules first popped up in the sediment, he was struck with the suspicion that they spoke of a behemoth from outer space.

Such spherules are formed when a catastrophic collision vaporizes rock, throwing it into the atmosphere in a great vapor plume. Small droplets of molten rock condense, solidify and fall back to the surface, there to be captured as a thin layer, forever a marker of a calamitous event.

Subsequent tests of this particular haul of spherules revealed elements such as platinum, nickel and chromium, represented at levels commonly found in asteroids.

The significance of the find lies in "understanding early bombardment rates on Earth and early crustal evolution," note the authors.