Shocking discovery: Electric eels can leap from water when threatened

Loading...

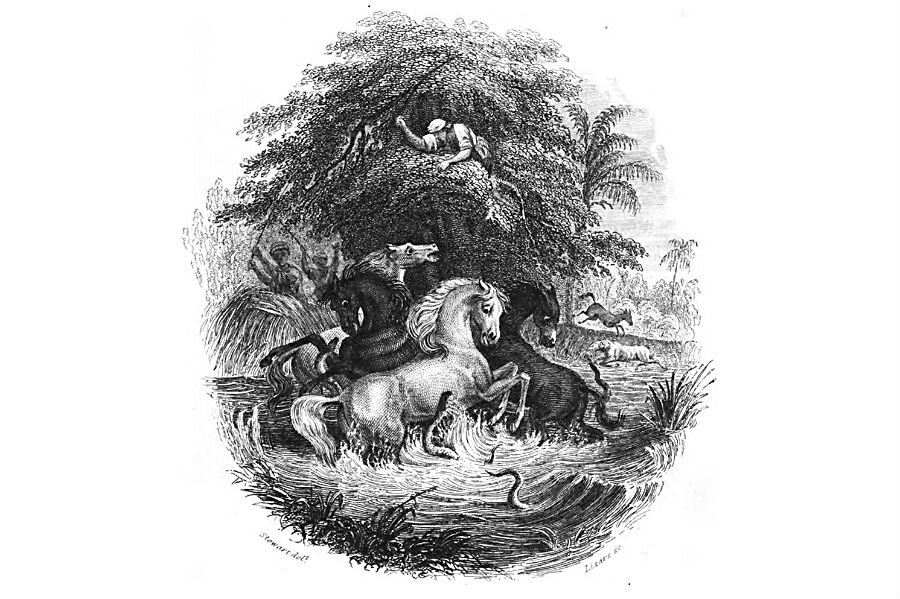

More than 200 years ago, renowned naturalist and explorer Alexander von Humboldt claimed to have witnessed a bizarre spectacle in South America, in which horses were locked in a deadly struggle with electric eels.

In the centuries following, von Humboldt's story was dismissed with varying degrees of derision, and nobody has been able to document a similar experience. Until now.

In a new study, published Monday in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, Kenneth Catania of Vanderbilt University describes some experiments that replicate this behavior, with electric eels leaping from the water to administer electric shocks.

"I certainly thought it was a crazy story when I did consider it," Dr. Catania, a professor of biological sciences who specializes in neuroscience and animal sensory systems, tells The Christian Science Monitor in a telephone interview, "but I don’t anymore. At this point I don't think he exaggerated one bit."

Humboldt's tale from the Amazon began with his offering payment to local fishermen to supply him with electric eels for study.

To assist in their task, the fishermen employed the services of horses and mules, herding about 30 into a pool known to contain eels. The sinuous fish responded by barreling towards the horses, pressing themselves against the beasts and discharging their electric shocks.

The mammals were prevented from fleeing by the fishermen, who had apparently climbed nearby trees and were shouting and waving branches to spook the creatures into staying in the water.

In the ensuing chaos, two horses drowned, and others collapsed by the pool's edge. Eventually, the eels were so exhausted that they were unable to shock anymore, making them safe to collect.

As Catania was working with his own eels, their behavior brought Humboldt's often-doubted story to mind.

"I had been studying electric eels for a while," says Catania. "During the course of these studies, I was moving the eels with a metal-rimmed net… and the eels periodically turned around and attacked the net."

Coupled with Humboldt's experience – and, in particular, an illustration of the event, which appeared to show the eels leaping to attack the horses, something Humboldt himself never explicitly described – the biology professor decided to investigate.

He designed an experiment that measured the voltage and amperage produced by the eels' shocking behavior, finding that both values increased dramatically the higher the creatures leapt. To illustrate the point, he covered a plastic alligator hand-puppet with LEDs, which lit up when they received an eel's charge, giving a visual representation of the pain the shock would produce.

In terms of efficiently applying an electric shock, this behavior makes sense: when an eel is fully submerged, the power it emits is dissipated in the water, meaning that any adversary would not receive the full effect.

But by removing itself somewhat from the water and making direct contact, the eel intensifies the sensation, and the more it rises from the water, the stronger the shock.

"Recognizing that the voltage imparted increases with the height of the eel coming out of the water explains how this could have evolved," Catania tells the Monitor. "It all fits so nicely with the successive stages required for selection."

But why would an eel want to attack something as big as a horse in the first place? Why not just swim away?

It turns out that the ecology of eels has a neat explanation for this, too.

The Amazon basin, where these creatures live, is a place dominated by two distinct seasons: one rainy, and one dry. During the former, waterways swell, banks burst, and floodwaters coat much of the land, giving the eels a huge range to play with. But as the dry season encroaches and the waters recede, the fish can often find themselves stranded in oxbow lakes or ponds.

Under such circumstances, if potential predators wander too close, the eels have nowhere to retreat to; their only choice is to attack. Additionally, some of these eels bear their young during the dry season, so having an effective defense would be even more crucial.

Catania's experiments lent further credence to this hypothesis, too, by demonstrating that when the water in the aquaria was lower, the eels were more aggressive, striking more quickly.

"This is a species people have studied for hundreds of years," he says. "Darwin worked with eels, and Faraday did, too. But mostly it's been about anatomy and physiology, less about behavior. It turns out their behavior is equally fascinating."