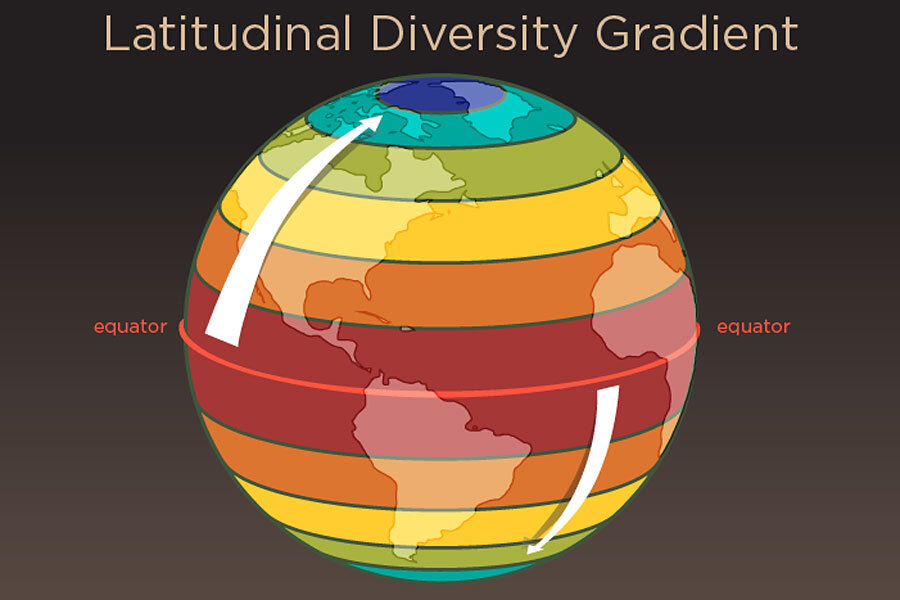

One of ecology's oldest puzzles: Why does diversity cluster near the equator?

Loading...

From plants to animals, insects to fish, mammals to reptiles, and vertebrates to invertebrates, there are generally more species at lower latitudes, closer to the equator, than at higher ones, closer to the poles. This pattern, called the latitudinal diversity gradient, "is a very ubiquitous pattern in ecology," says Jonathan Marcot, of the University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign.

Today it might seem obvious that species diversity clusters around the equator. But, according to Dr. Marcot's research on mammals detailed in a paper published Monday in the journal Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, it hasn't always been like that.

And the way global species diversity has changed over time could help scientists resolve a two-century old puzzle.

Starting with famed 19th century naturalists Charles Darwin and Alfred Russel Wallace, scientists have been spotting the latitudinal diversity gradient everywhere they look, across many different types of organisms, says Gary Mittelbach, an ecologist at the W.K. Kellogg Biological Station at Michigan State University, who was not part of Marcot's research team.

"It was considered conventional wisdom that this is what life does, this is how life works on this planet," Marcot tells The Christian Science Monitor.

Despite this near observational consensus, "It's been hard to come up with an agreed upon explanation," Dr. Mittelbach tells the Monitor.

"The problem is that we have too many ideas of what causes it," Marcot says. And a lot of those explanations are difficult to disentangle from the others.

And now, after studying the fossil record of mammals across North America from the 25 to the 70 degree N latitude line, Marcot and his team find that the latitudinal diversity gradient might not be so ubiquitous after all.

"We found that for most of the last 63 million years, there was very little evidence for a strong gradient at all," he says.

But not all is lost. The evolution of this pattern over time could help explain why the latitudinal diversity gradient exists.

Because the phenomenon appears across all life, scientists expect there to be a very general explanation, something that affects life all across the globe, Mittelbach says. So if that general characteristic has changed in the past, you would expect to see the diversity pattern change as well.

Marcot and his team found that the current, strong gradient seems to have evolved just over the past 4 million years or so.

So what was happening around that time? The Earth was cooling down, heading into the last ice age.

"We found a significant correlation between changes in global temperature and the strength of the gradient," Marcot says. The cooler the global temperature, the more likely mammal species diversity would increase at lower latitudes, the team found.

"They're probably correct in pointing out that temperature is part of the explanation here," Mittelbach says. He is not surprised, as other research teams studying different parts of the fossil record have suggested such an explanation. "I think that people are kind of coming to the conclusion that it's stronger in this kind of icehouse world than it was in the greenhouse, or hothouse, world," he says. And this study is "another piece of the puzzle."

Mittelbach adds that other research has shown evidence for a strong latitudinal gradient at other times in Earth's history. "It's kind of waxed and waned," he says, "but it's been there before."

This research doesn't just shed light on the past, adds Marcot.

"We know that humans are influencing the climate of the planet, but what we don't really know is how life on the planet is going to respond to that," he says. "This gets us one step closer to understanding how climate influences the distribution of mammals on the global or continental scale."