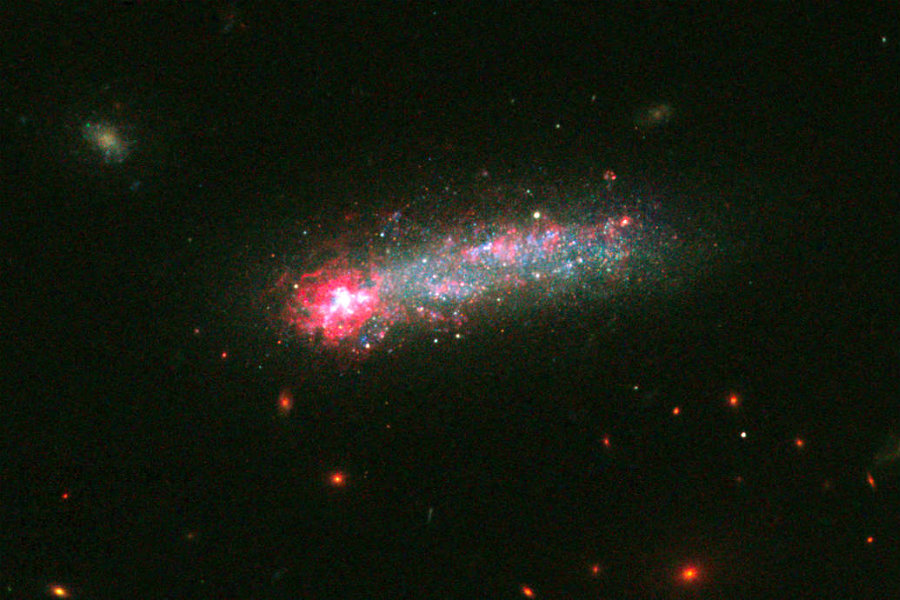

Hubble reveals stellar fireworks in 'skyrocket' galaxy

Loading...

NASA’s Hubble Telescope has once again captured a brilliant cosmic phenomenon, with images of an intense episode of star creation in a galaxy far, far away.

The tiny galaxy, named Kiso 5639, is home to an unusual star nursery that has astounded astronomers with the sheer volume of baby stars it produces. Yet as different as this galaxy may seem, astronomers say that it can teach us a lot about the way our own Milky Way galaxy has evolved.

“This galaxy is similar to what our galaxy might have looked like before it evolved into the pinwheel shape we see today,” said astronomer Debra Elmegreen, the lead researcher on the project, in a phone interview with The Christian Science Monitor. “It helps give us insight into why our galaxy is the way it is now.”

According to Dr. Elmegreen, elongated galaxies such as Kiso 5639 were fairly common when the universe was half as old as it is today. In fact, about half of the galaxies that astronomers are aware of today do not look as they did in their early lives, most of which began about a billion years after the universe was formed.

“It's fun to study galaxy evolution,” Elmegreen says, “because it gives us a sense of our little place in the universe. It gives us a glimpse of the past.”

“By comparing local galaxies to galaxies early in the universe,” astronomer and study co-author Marc Rafelski tells the Monitor, “we can interpret what is going on in the early universe.”

Elongated, or “tadpole,” galaxies like Kiso 5639 are common in the early universe. (Kiso 5639 is actually shaped like a pancake, rather than a tadpole, according to astronomers, who say that the angle at which we view the galaxy distorts its appearance.) What looks like the tadpole’s head is 2,700 light years across, and is dotted with little star clusters that are, on average, less than a million years old, say scientists.

But why is one area of little Kiso 5639 producing stars at such a rapid rate?

From their analysis of about ten local tadpole galaxies, astronomers know that the brightly shining “head” of Kiso’s tadpole shape has an unusual gaseous composition.

Whereas gas composition in galaxies is normally mostly hydrogen and helium with a smaller amounts of carbon and oxygen and other elements, the gaseous composition of Kiso's head has very low metallicity levels, suggesting that there is more gas coming from elsewhere in the universe.

“The metallicity suggests that there has to be rather pure gas, composed mostly of hydrogen, coming into the star-forming part of the galaxy, because intergalactic space contains more pristine hydrogen-rich gas,” said Elmegreen in a press release. “Otherwise, the starburst region should be as rich in heavy elements as the rest of the galaxy.”

Astronomers have taken this star nursery as evidence that there is possibly a “cosmic web” of gases stretching throughout the universe, occasionally feeding galaxies. And because Kiso 5639 is spinning, the portion that is enriched today may not be the star nursery of tomorrow.

“Many people have the idea that galaxies are islands in the universe,” researcher and study co-author Jay Gallagher tells the Monitor by phone, “but this discovery helps us to understand how galaxies feel the effects of their surroundings."

Dr. Gallagher tells the Monitor that there is a substantial amount of stray matter in the universe. We don’t know where that matter is, he says, but we do know that galaxies feed off of something, and understanding star creation in tadpole galaxies such as Kiso 5639 could help help us learn.

Kiso 5639’s proximity to our own galaxy, just 82 million light years away, is a boon to astronomers who seek to study galaxy evolution, according to researchers.

“Imagine you’re studying the ruins of the pyramids,” said Gallagher, “and then imagine you look again and see another pyramid being built right in front of you. You’d be able to better understand what was going on.”