Mars atmosphere was once rich with oxygen, say scientists. Where did it go?

Loading...

Early Mars might have had both liquid water on its surface and oxygen in its atmosphere, according to a new study published in Geophysical Research Letters.

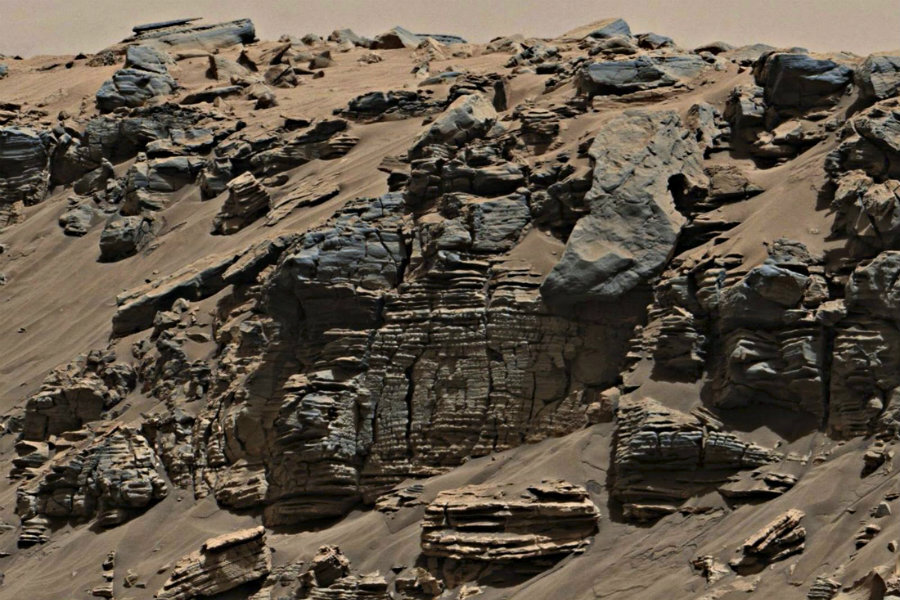

Findings by NASA’s Curiosity and Opportunity rovers reveal that, beneath the Red Planet’s dusty surface lurk substantial deposits of manganese oxide, a compound likely created by a marriage of liquid water and atmospheric oxygen.

“This is a piece of the puzzle in our understanding of early Mars,” study co-author Raymond Arvidson tells The Christian Science Monitor in a phone interview, “and the potential for habitation on a planet like Mars.”

Manganese is very difficult to oxidize, according to the study’s lead author Nina Lanza, requiring large quantities of liquid water and a lot of oxygen.

Although other chemical reactions can oxidize manganese, Dr. Lanza tells the Monitor, oxygen is the most likely culprit.

When Curiosity found high concentrations of manganese oxide in a crater on Mars, Lanza says, scientists using the ChemCham (a rover tool that analyzes the chemistry rock and mineral samples) were surprised.

On Earth, manganese oxides are created by either the presence of oxygen, or tiny creatures called microbes. Researchers say that the former is far more likely on Mars than the latter.

Free oxygen on Earth was rare before life evolved and began the process of photosynthesis, explains Lanza, so oxygen can serve as a biosignature, or a sign that a planet has life.

But if Mars had enough oxygen to oxidize manganese, scientists may have to reevaluate the idea of oxygen as a biosignature, she says, as this provides evidence for a highly oxygen-rich atmosphere at one point in Mars’s history, but there is still no proof of life.

So where, then, did all of Mars’s oxygen go?

Into the rocks. “Oxygen is very reactive,” says Dr. Arvidson, “and unless you replenish it, it would be consumed very quickly.”

As Mars’s liquid core cooled, probably about 4.2 billion years ago, its magnetic field grew weaker and weaker, leaving its atmosphere susceptible to solar winds. At that time, Mars likely had a lot more water than today. Without a magnetic field to protect it, radiation could have split water molecules into hydrogen and oxygen. Solar winds would have stripped away the lighter hydrogen atoms, leaving behind oxygen atoms to rust (oxidize) surface minerals and turn the planet red.

“This tells us that Mars has evolved very differently than we thought it did,” Lanza told the Monitor. “We need to start looking for different types of minerals and other evidence about Mars’s past.”

Researchers are quick to caution that the presence of a more oxygen-rich atmosphere does not mean that Mars ever played host to life, or that it was even truly Earth-like. But it is a clue.

“It is another piece of the puzzle,” reiterates Arvidson.

“This is the first step towards understanding planets like Mars,” says Lanza, “but it is not the last step.”