Myth meets science: Did researchers just verify a Chinese legend?

Once upon a time, a mighty flood swept through a Chinese valley destroying everything in its path and making the land uninhabitable. But then a man named Yu came along and tamed the great flood. The heroic Yu went on to become Emperor Yu, the ruler of China's first dynasty.

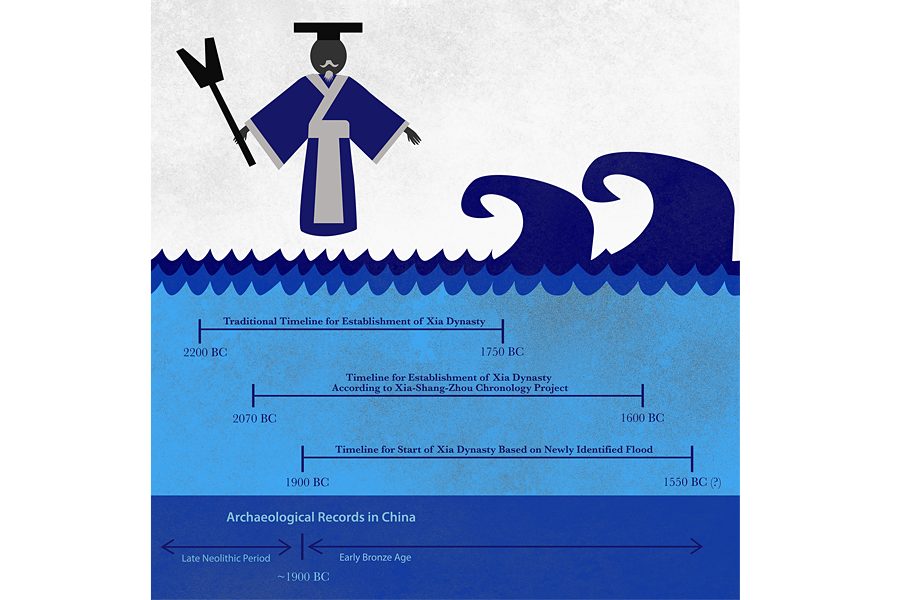

Unfortunately for historians, there was little evidence of such a flood actually happening 4,000 years ago, and no proof that Yu or his Xia dynasty actually existed. In fact, the first account of this ancient legend was written down at least five centuries later, so it seemed impossible to confirm.

Until now.

A team of geologists, archaeologists, and historians say they have uncovered rock-solid proof that the flood actually happened, and it could have been just devastating enough to stimulate innovation and a cultural shift to have kicked off China's Bronze Age and first empire.

The first hint came when the study's lead author, geologist Qinglong Wu, found ancient lakebed sediments in the Jishi Gorge, a valley in the upper part of the Yellow River, in 2007. He conjectured that some sort of natural dam could have blocked the river sufficiently to form a lake in that spot.

And if that dam collapsed, he realized, there would have been a massive flood.

So Dr. Wu went downriver to look for evidence of such an "outburst flood." Sixteen miles downriver, Wu found just what he was looking for: a thick layer of sediments that correlated to those found in the Jishi Gorge.

That's when Wu realized he might have found the real event behind the Xia dynasty legend.

Not wanting to invite laughter, he told Science Magazine, he gathered an interdisciplinary team to take a closer look at the ancient sediments in the region. The result of that collaboration was published Thursday in a paper in the journal Science.

Here's how the story goes, according to Wu and his colleagues:

Around 1920 BC, give or take a decade or two, an earthquake ripped through the region, cracking the ground and triggering landslides around the Yellow River.

The shaking, cracking Earth destroyed cave dwellings in a Neolithic settlement called Lajia and killed some of its inhabitants, leaving an archaeological treasure trove for scientists to find in the 1990s. An enormous rockslide poured into the river itself, stopping its flow.

That massive natural dam, more than 650 feet tall, created the lake in the Jishi Gorge that Wu first discovered.

The water pooled up in the new lake for six to nine months. Once the water began spilling over the top of the dam, the rubble would have washed away quickly, releasing the pent-up floodwaters.

When the water rushed out of the Jishi Gorge, it forced the river in new directions, demolished everything in its path, and filled the lowlands with water. Mud coated the farmlands and filled the cracks in the ground at Lajia, left behind from the earthquake.

And this could have set the stage for a heroic figure – like, say, Emperor Yu – to sweep in to try to control the river.

"The outburst flood … provides us with a tantalizing hint that the Xia dynasty might really have existed," study co-author David Cohen of National Taiwan University says in a press conference. "Here we have evidence for a natural event that could have eventually been recorded as the great flood. If the great flood really happened, then perhaps it is also likely that the Xia dynasty really existed too."

But some aren't ready to jump to that conclusion.

"I really do not see how we can jump from one to the other," historian Frank Dikotter at the University of Hong Kong told Quartz. Instead, he sees this as a scientific attempt to reinforce the "national myth [of a] zhonghuaminzu, the Chinese nation."

The key link between the flood and the Xia dynasty is the timing, Dr. Cohen told New Scientist. "It corresponds so closely in time with the legends of the flood and the beginning of the Bronze Age in China."

Paul Goldin, who studies China’s Warring States period at the University of Pennsylvania, told the New York Times that the legend of Yu and the flood were likely created to reinforce the power of later dynasties.

"These are relatively late legends that were propagated for philosophical and political reasons, and it’s inherently questionable to suppose that they represent some dim memory of the past," he said.

Will this controversy ever be resolved?

"It’s probably beyond the reach of science to ‘prove’ the origin of an oral tradition handed down generation to generation for a thousand years before the first written records," David Montgomery of the University of Washington in Seattle told New Scientist. But this study "supports the historicity of events central to the early history of Chinese civilization, and provides another example of how some of humanity’s oldest stories — tales often taken as mythology or folklore — may be rooted in natural disasters that really happened."