New software can track global poverty...from space

Loading...

Around the world, there are people who need help. But sometimes, populations of poverty-stricken people are difficult to find.

That is why researches at Stanford have put together a program to find people who need help, from space.

One of the many difficulties in dealing with poverty is simply not knowing where to send aid. In many poor countries, data on which areas need the most help are hard to get.

According to World Bank data cited in the Stanford team's press release, 39 out of 59 African countries conducted fewer than two surveys substantial enough to result in poverty measures between 2000 and 2010.

Such surveys are costly and often difficult, especially in war-torn countries. Nevertheless, the data is of great importance for policymakers who want to help.

The Stanford team's new program is a new way acquire poverty-distribution data affordably and efficiently using a machine-learning technique called a convolutional neural network and images of the planet taken by satellites orbiting it.

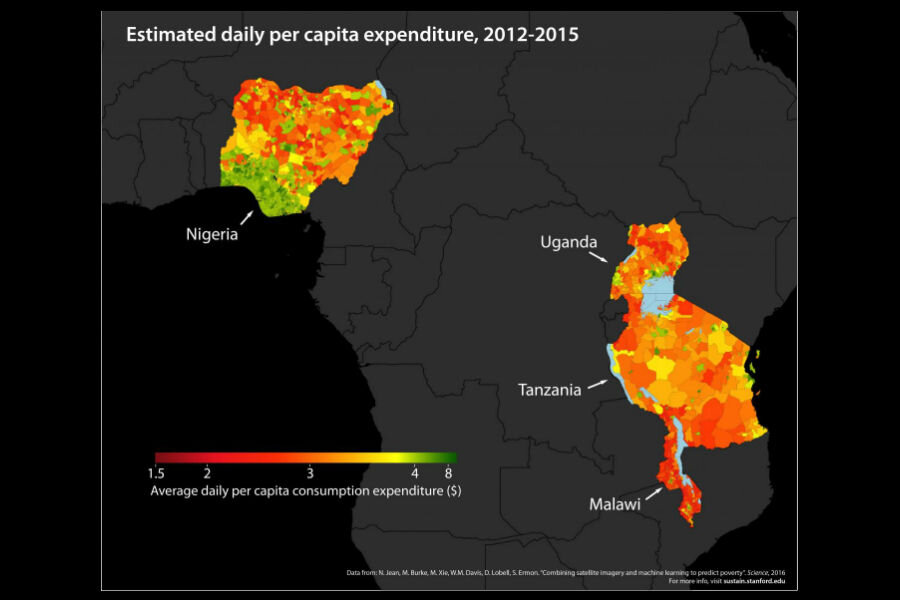

In an article published in the journal Science, the team used only publicly available data to train the neural network to identify features associated with poverty from satellite images in Nigeria, Tanzania, Uganda, Malawi, and Rwanda. The countries were chosen because of reliable data about poverty distribution with which to compare the program's results.

The program is able to distinguish and flag various features that indicate poverty. At night, areas with less light indicate less wealth, but the team found that daytime data was even more useful. In daylight, the program can tell the difference between rooftops made of metal and rooftops made from mud or thatch. The program can also make predictions of poverty based on distance from city centers.

"Without being told what to look for, our machine learning algorithm learned to pick out of the imagery many things that are easily recognizable to humans – things like roads, urban areas and farmland." said Neal Jean, the lead author of the Journal study in a statement.

These factors are useful in determining how much money is running through an area, and, by extension, the relative level of wealth of the people living there, according to The Los Angeles Times. In fact, the new method has already yielded more accurate results than many more traditional methods of gathering data. In Rwanda, program predicted average household wealth better than cell phone records.

The program is still in the early stages of development, and will require a lot more refinement and traditional surveys to verify its potential accuracy. But with a little bit of work, the program eventually use use daytime satellite data to locate areas of poverty at virtually no significant cost, using publicly available satellite imagery.