Astronomers discover a dark-matter galaxy: Dragonfly 44

Loading...

Like many great science stories, it all began with a smudge.

A group of astronomers at Yale University and the University of Toronto were peering through a telescope they had built from camera parts when they saw something that could change the universe.

"We planned to study the outskirts of galaxies to see what exists around them, but by accident we saw all these little smudges," Pieter van Dokkum of Yale University told The Washington Post.

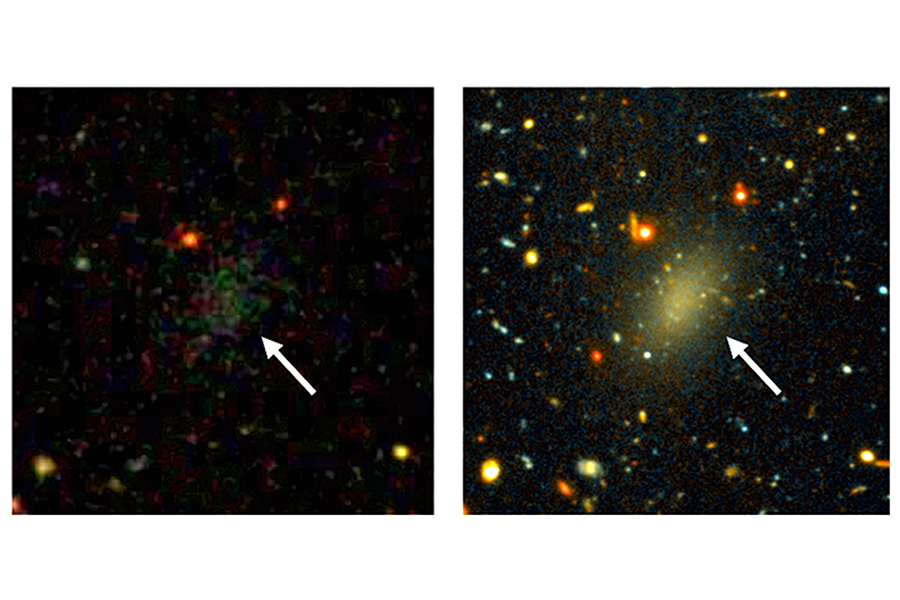

No, their scrappy, self-made Dragonfly Telephoto Array telescope wasn't defective. It had picked up on what could represent an entirely new class of massive objects: a galaxy 320 million light-years away that is 99.99 percent dark matter.

To confirm their discovery, Dr. van Dokkum and his colleagues turned to more conventional telescopes: the W.M. Keck Observatory and the Gemini North telescope in Hawaii. And they found that the dark galaxy, dubbed Dragonfly 44, was surprisingly massive.

The scientists measured the velocities of the stars in the newfound galaxy to determine Dragonfly 44's mass, as speedier stars mean a more massive galaxy. Their findings are described in a paper published Thursday in Astrophysical Journal Letters.

"Amazingly, the stars move at velocities that are far greater than expected for such a dim galaxy. It means that Dragonfly 44 has a huge amount of unseen mass," study co-author Roberto Abraham of the University of Toronto said in a press release.

The scientists estimate that Dragonfly 44 has a mass about 1 trillion times the mass of the sun, which is equivalent to 2 tredecillion kilograms (a 2 followed by 42 zeros, so a lot of mass).

That means Dragonfly 44 is as massive as our own star-filled galaxy, although it only has 0.01 percent of the stars and "normal" matter that fills the Milky Way. The remaining 99.99 percent of Dragonfly 44's mass must, therefore, be dark matter, the researchers concluded.

Dark matter has yet to be directly detected, but scientists have hypothesized that it makes up about 27 percent of the mass of the universe, making itself known only through its gravitational pull. [Editor's note: An earlier version overstated the amount of dark matter thought to exist in the universe.]

"Ultimately what we really want to learn is what dark matter is. The race is on to find massive dark galaxies that are even closer to us than Dragonfly 44, so we can look for feeble signals that may reveal a dark matter particle," van Dokkum said in the press release.

Dragonfly 44 is not the first dark galaxy to be discovered, but it stands out because its mass is so similar to the Milky Way.

"We have no idea how galaxies like Dragonfly 44 could have formed," said Dr. Abraham. "The Gemini data show that a relatively large fraction of the stars is in the form of very compact clusters, and that is probably an important clue. But at the moment we’re just guessing."

But the astronomers do know they've found something significant.

"We think that this galaxy is representative of an entirely new class of object," van Dokkum told the Post. "It’s not some weird singular galaxy that’s just a curiosity."