How an ancient skeleton may uncover secrets of the Antikythera shipwreck

Loading...

Nearly 2,100 years ago, a large ship sank off the Greek island of Antikythera in the Aegean Sea, leaving its cargo scattered across the seafloor. Today, underwater archaeologists have found human remains, well-preserved enough that scientists may be able to extract DNA.

If they're successful, this could yield insight into the lives of the people aboard the ship and their people.

"Archaeologists study the human past through the objects our ancestors created," said Brendan Foley, a marine archaeologist with the Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution (WHOI), in a press release. "With the Antikythera Shipwreck, we can now connect directly with this person who sailed and died aboard the Antikythera ship."

The Antikythera Shipwreck was first discovered in 1900 by Greek sponge divers. With a bounty of artifacts, including a clockwork device, dubbed the 'Antikythera mechanism,' that has been called the first computer, the wreck has attracted significant attention.

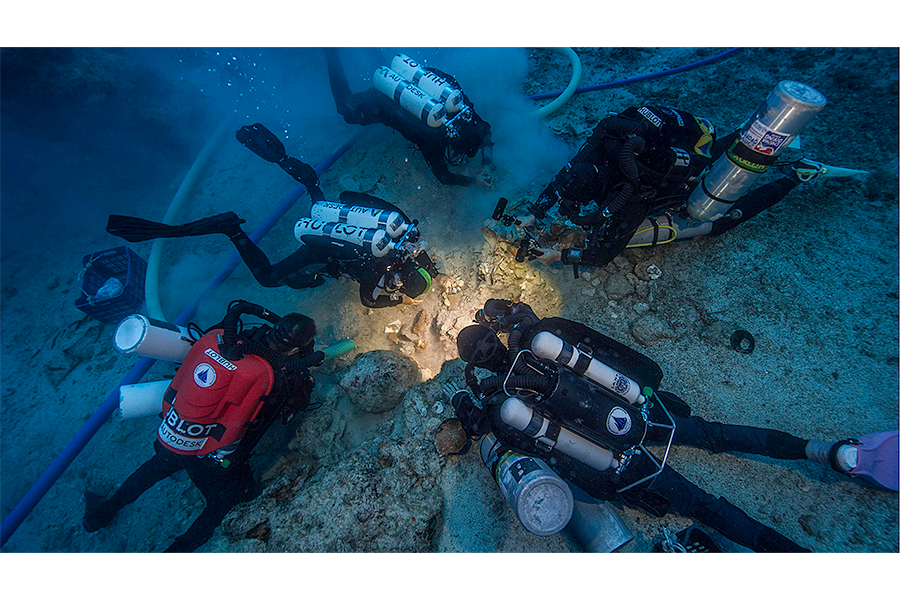

When it was first discovered, the visible parts of the wreck were thoroughly picked over. But a team of archeologists led by WHOI scientists and researchers from the Hellenic Ministry of Culture and Sports returned to dig beneath potsherds and sand for more artifacts.

Beneath about a foot and a half of debris lay a human skeleton.

"We’re thrilled," Dr. Foley told Nature News. "We don’t know of anything else like it."

The archaeologists found a partial skull, three teeth, leg and arm bones, and pieces of rib. But most enticing was that both petrous bones – dense bones behind the ear that provide the best possibility of holding the seafarer's DNA – are among the bones.

"If there's any DNA, then from what we know, it'll be there," Hannes Schroeder, a specialist in ancient-DNA analysis at the Natural History Museum of Denmark in Copenhagen who the team brought in to help with the analysis, told Nature News.

The team is holding off on their attempt of DNA extraction until permission is granted by the Greek authorities.

The remains are thought to be those of a young man. The bones are stained amber red by the corroded iron objects that surrounded them. This hints that perhaps the victim was a slave, unable to escape because of his chains.

Scientists note that it is rare for skeletons to be found in shipwrecks, as victims are usually swept away, decay, or are eaten by marine animals. But, as this was a particularly large ship, the victims may have been trapped below decks when their ship sank.

DNA analysis could help sort out the victim's age and familial heritage and better paint a picture of the story of this ship's last voyage.

Laden with luxury items, the ship was probably traveling from Greece to Rome, say historians. DNA analysis could help confirm or challenge that story.

These aren't the first human remains to be discovered at the Antikythera shipwreck. French marine explorer Jacques Cousteau discovered bones scattered across the wreckage in 1976, thought to belong to at least four individuals. But at the time, ancient DNA analysis was not an option.

This report contains material from the Associated Press.