How otter pelts are revolutionizing human wetsuits

Loading...

The sunny beaches of summer are already losing their popularity, as increasingly chilly waters drive vacationers to less frigid pursuits. Cold water has long challenged humans, who have no natural defenses against a wintry marine environment.

Beavers and sea otters, on the other hand, thrive in cold water, despite lacking the insulating blubber that protects other marine mammals. The secret is in their fur, where warm air is trapped among the hairs in their thick pelts, keeping them warm even as they dodge ice floes.

Researchers at Massachusetts Institute of Technology in Cambridge, inspired by this evolutionary strategy, have created synthetic pelts modeled after the mechanism through which beavers warm themselves. They hope that the technology can be used to create wetsuits to keep humans warm in freezing water.

"Air is about 20 times less thermally conductive than water, which means it is an excellent insulator," Alice Nasto, lead author of the paper and a graduate student at MIT, tells The Christian Science Monitor. "When a layer of air is trapped between skin and cold water, it provides protection against the cold."

She and her colleagues published a study this summer in Physical Review Fluids that examined two types of hair unique to semiaquatic animals like beavers and otters. Long "guard" hairs grab water drops, keeping the water from penetrating the short layer of "underfur," where air pockets create an insulating layer against the animals' skins.

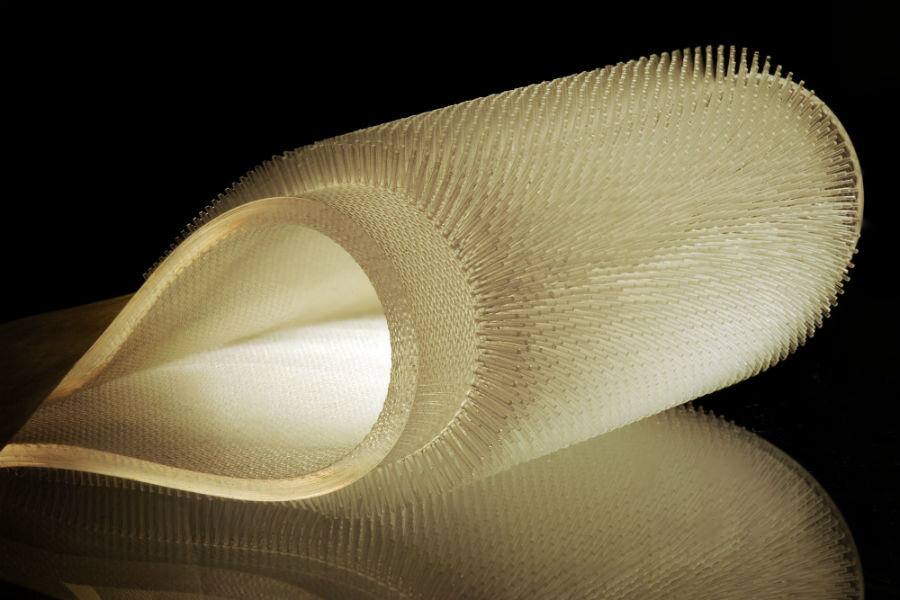

In order to examine the properties of these hair layers, the researchers made molds of plastic "hair" of varying densities, created with the help of a computer program. They found denser concentrations of fur were able to trap more air in the underfur region, as long as they submerged quickly, like an otter diving.

The ability to dive and move quickly is important to small, semiaquatic mammals, says Ms. Nasto.

"If you're a large aquatic mammal, you can carry a thick layer of blubber without too much trouble," she explains. "For a small animal, the thickness of blubber required for effective insulation would be very heavy. Fur-based insulation helps smaller animals stay agile because it is lightweight compared to blubber."

An animal the size of an otter weighed down by blubber would be an easy target for predators, and would require a great deal more food to maintain enough fat to remain warm during the winter, she adds.

The researchers were inspired by a trip to a Taiwanese wetsuit manufacturer during a trip facilitated by Sports Technology and Education at MIT (STE@M), a program that encourages students and faculty to pursue projects relating to sports technology.

"They are interested in sustainability, and asked us, 'Is there a bioinspired solution for wetsuits?' " Anette (Peko) Hosoi, study co-author and professor of mechanical engineering at MIT, told MIT News. "Surfers, who go in and out of the water, want to be nimble and shed water as quickly as possible when out of the water, but retain the thermal management properties to stay warm when they are submerged."

Surfing requires the ability to make several dives in short succession without depending on bulky heat retention equipment – very similar to the evolutionary requirements of beavers and otters. By creating a synthetic beaver pelt, the researchers hope to revolutionize cold-water surfing.

"Currently, wetsuits are made of heavy neoprene rubber materials," says Nasto. "Interestingly, air is 10 times more insulating than neoprene rubber. So if you could make a suit from a textile that traps the same thickness of air as the thickness of air a typical rubber suit, it would be 10 times as insulating and also more lightweight."

The new wetsuit idea is one of many new technologies directly inspired by structures and processes that already exist in nature.

"For example, spider webs and honeycombs have inspired materials that are strong and lightweight," Nesto says. "Roboticists often look to emulate the swimming and walking gaits of animals for new locomotion mechanisms."

Evolution offers countless solutions to problems that face scientists and engineers, but the trick is identifying exactly how they work.

"People have known that these animals use their fur to trap air," Hosoi said. "But, given a piece of fur, they couldn’t have answered the question: Is this going to trap air or not? We have now quantified the design space and can say, 'If you have this kind of hair density and length and are diving at these speeds, these designs will trap air, and these will not.' Which is the information you need if you’re going to design a wetsuit."

She joked, "Of course, you could make a very hairy wetsuit that looks like Cookie Monster and it would probably trap air, but that's probably not the best way to go about it."