423-million-year-old fish fossil sheds light on evolution of animals' jaws

Loading...

A 423-million-year-old fossil is rewriting the history of how jaws evolved, according to a team of Swedish and Chinese researchers who published their findings Friday in the journal Science.

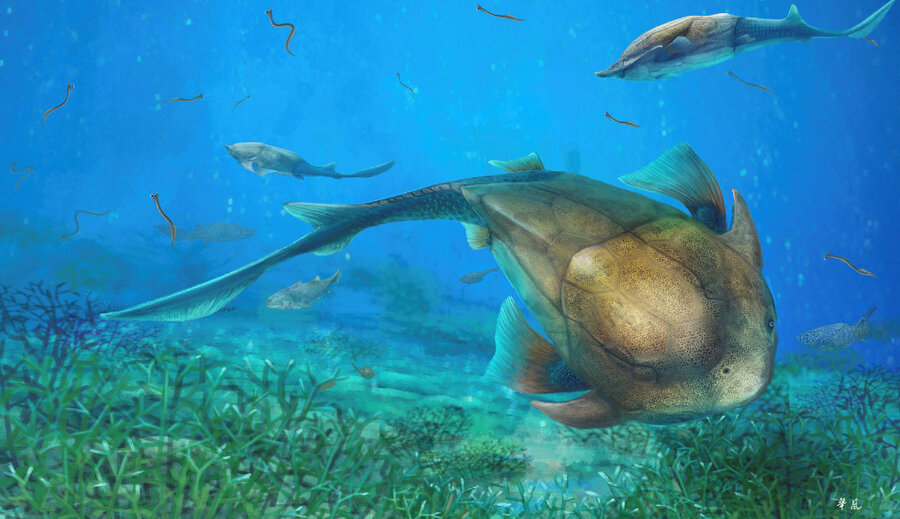

The fossil was discovered in China's Yunnan province and belonged to Qilinyu rostrata – a bottom-dwelling, armored fish that belongs a prehistoric class known as placoderms. Although scientists have believed placoderms to be an evolutionary dead end, this fossil’s jaw bones suggest the fish could have played a key role in vertebrate evolution.

“Anything from a human being to a cod has recognizably the same set of bones in the head,” study coauthor Per Ahlberg, a paleontologist at Uppsala University in Sweden, told Science News. “Where did these bony jaws come from?”

Early vertebrates appeared more than half a billion years ago, equipped with sucker-like mouths, not jaws. Scientists had observed a jaw-like structure in early placoderms, but their jaws were so different from modern ones that for many years scientists concluded that bony fish and the rest of modern jaw users could not have evolved from them.

Early placoderm jaws "look like sheet metal cutters," Dr. Ahlberg told Science News. "They’re these horrible bony blades that slice together.… The established view is that placoderms had evolved independently and that our jaw bones must have a separate origin."

However, the discovery of a Qilinyu fossil and Entelognathus primordialis, another placoderm genus discovered in 2013, may have created the missing evolutionary links between the three bones first found in bony fish and the “sheet metal cutters” of the early placoderms.

The Qillinyu fossil, a more modern placoderm, shows clear signs of all three modern jaw bones: the maxilla, premaxilla, and dentary.

“We’ve suddenly realized we had it all wrong,” paleontologist John Maisey of the American Museum of Natural History in New York City, who was not involved with the work, told Science News.

According to the study published Friday, bony fish and placoderms should no longer be considered two different branches of the evolutionary tree, with the latter branch dying off long ago and all modern jawed vertebrates coming from the former.

"Now we know that one branch of placoderms evolved into modern jawed vertebrates," study co-leader Zhu Min, a paleontologist at Chinese Academy of Sciences' Institute of Vertebrate Paleontology and Paleoanthropology, told Reuters. "In this sense, placoderms are not extinct."

This report includes material from Reuters.