Can you tell where a bird is from just by looking at its wings?

Loading...

Some birds have short wings, and some have long wings. Some birds have pointed wings, and some have rounded wings. And those distinctions may have to do with where they live.

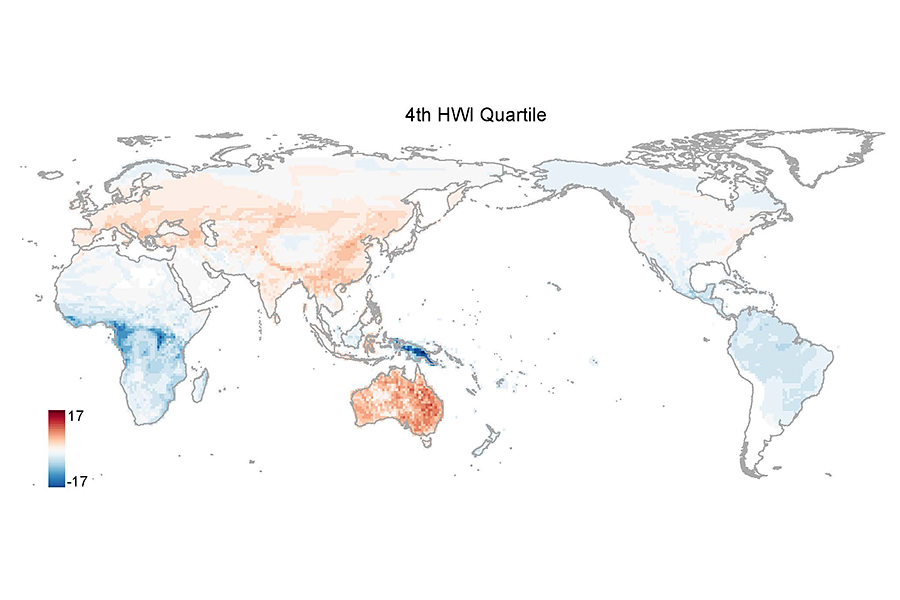

A new study finds that birds that live closer to the equator have shorter, rounder wings than those that live farther away.

This is a pattern that scientists have always suspected to be the case, but there had not been a comprehensive assessment of the evidence – until now.

A team of researchers studied thousands of specimens in natural history museum collections, representing 782 species of corvoid birds, in an effort to suss out patterns of diversity across the globe. Their results were published Wednesday in the journal Proceedings of the Royal Society B.

"The pattern has generally been thought to be quite likely by scientists for some time. But this was really the first actual empirical evaluation of it across a large group of birds," study lead author Jonathan Kennedy, a researcher at the Center for Macroecology, Evolution and Climate at the Natural History Museum of Denmark, University of Copenhagen, tells The Christian Science Monitor in a phone interview.

"This research corroborates previous studies that documented a link between a bird's morphology, including wing shape, and where the bird occurs in the landscape," Robb Brumfield, the director of Louisiana State University's Museum of Natural Science, who was not part of the new research, agrees in an email to the Monitor.

These findings are unsurprising, Dr. Kennedy says, because of the different advantages that different wing shapes and sizes give a bird. For example, the scientists expected to find that birds from northern, temperate regions have pointier, longer wingtips because they make it easier for the birds to soar long distances. Birds living in those chillier regions usually go on long annual migrations to winter in warmer regions closer to the equator.

On the flip side, birds with shorter, rounder wings would be able to dart through dense tropical vegetation more easily. And, because they find all the food and other resources they need in the regions near the equator, they wouldn't need wings well-adapted for long journeys.

This makes sense evolutionarily, too, Dr. Brumfield says. "For example, bird species found on oceanic islands will often have wing morphologies that are better for long-distance flight, reflecting their ability to have colonized the island in the first place. In contrast, bird species that spend their entire lives in the dark understory of a continental tropical forest will typically have wing morphologies that are better for short-distance flight."

One of the reasons the researchers studied corvoid birds is that they are a superfamily within the Passeriform order. Passerine birds, also known as songbirds, make up about two-thirds of all bird species globally, Kennedy explains, and Corvoidea make up about a sixth of that order. But most importantly, he says, "they're present on almost all of the world's continental landmasses. That's everywhere except Antarctica."

As such, Kennedy says, "I would expect that this pattern is very consistent across passerine birds." So by studying Corvoidea – crows, ravens, jays, and their relatives – the researchers were able to tap into broader patterns.

Although this pattern fits with ecologists' and ornithologists' expectations, articulating the pattern could help scientists better understand broader evolutionary patterns.

When Kennedy and his colleagues started to measure bird wings, they were looking to see if there was a correlation between diversification and dispersal ability.

The idea was that perhaps an animal's ability to disperse across more landscapes and establish populations in new habitats would drive a diversity of species, as the animals would be adapting to new niches. So the team used wing shape as a proxy for dispersal ability.

But they found, at best, a weak correlation between present-day wing morphology and diversification rates.

"They suggest that there was an influence of past wing morphology," Melissa Bowlin, an ecologist and evolutionary biologist studying migratory birds at the University of Michigan-Dearborn who was not part of the research, says in a phone interview with the Monitor. "But unfortunately we don't know what the wing morphology was like in the past."

So, Dr. Bowlin says, it remains an open question whether dispersal ability affects diversification.

She adds that by not finding a significant relationship between the two, the research "confirms some things that we suspected about wing shape and how quickly that can evolve." She explains that because wing shape has likely evolved since the organisms diversified, that's why the researchers don't find a correlation between present-day wing shape and the diversity of corvoid species alive today.

"The reason why scientists care about questions like this is that we currently have major problems with invasive species all over the world. These species are coming in and destroying native species or replacing native species, and it's a serious conservation issue," Bowlin says. "One of the things that we don't understand is what characteristics of a species make it a good invasive species. We think that dispersal ability probably affects that, but we don't know. So that's one of the things that these authors were trying to figure out. Does dispersal ability essentially make for a good invasive species?"

And although that question remains open, Kennedy says his research does show that "wing morphology and its evolution is an extremely complex process. It's only by studying across a group of birds, like this, that we can expect to understand the general principles."

And, he adds, "Because all birds have wings, there is this assumption that they are all particularly capable fliers." But it's just not the case that flight capability is that uniform.