Titan's 'magic islands' may actually be fizzy nitrogen bubbles

Loading...

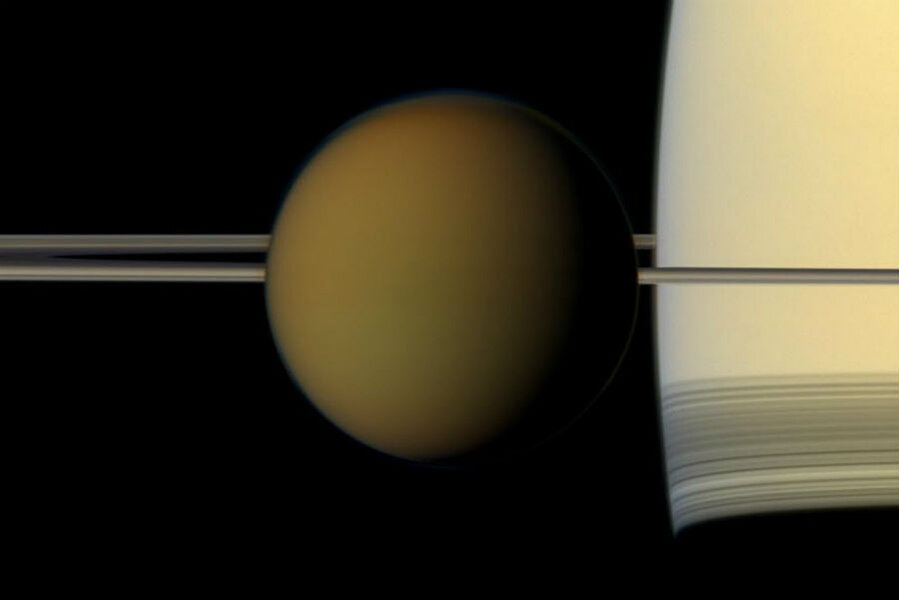

Titan is Saturn's largest moon. Its thick atmosphere and lakes made of liquid methane and ethane have made it one of the most mysterious and intriguing bodies in the solar system.

One of the strangest puzzles associated with the moon are the so-called "magic islands" that have appeared in some of the lakes and seas. These islands will appear in some photos from NASA's Cassini probe, but appear to have vanished in others. One of the hypotheses put forward to explain the phenomenon is that there could be large areas of bubbles that could erupt from the surface of the lake, sizzle on the surface for a while, and then disappear. In sufficiently large quantities, these areas of bubbles could easily be mistaken for islands, but the mechanism by which such bubbling could occur had not been tested in laboratory conditions.

But now, researchers at the Jet Propulsion Lab (JPL) in Pasadena, California have found that the conditions of Titan's surface lakes might be conducive to the production of large amounts of nitrogen bubbles, which could how these "islands" are able to pull off their cosmic magic trick.

In a NASA-funded study, which was published in the journal Icarus, researchers used data from the Cassini spacecraft to duplicate the conditions of Titan's lakes and oceans in order to test the solubility of nitrogen in these bodies of methane and ethane. They found that small variations in temperature, pressure, and composition of the lakes on Titan could cause nitrogen that had been absorbed into these liquids to suddenly and violently separate themselves from the solution. The phenomenon is similar to the way that opening a bottle of soda will cause the carbon dioxide to suddenly release, causing a rush of fizzy bubbles.

The nitrogen fizz could easily be prompted by changing temperatures depending on the seasons, or even incidental weather patterns.

"Our experiments showed that when methane-rich liquids mix with ethane-rich ones – for example from a heavy rain, or when runoff from a methane river mixes into an ethane-rich lake – the nitrogen is less able to stay in solution," Michael Malaska, who led the study, said in a statement.

Titan is the only body in the solar system, apart from Earth, that is known to support stable bodies of liquid on its surface. Earth's relative closeness to the sun means that the planet is warm enough to support stable liquid water, but Titan is much farther away from this heat source. As a result, liquid water can only exist on Titan far beneath the surface, closer to the moon's core, while methane and ethane dominate the surface.

Since Titan's surface temperature clocks in at around -179 degrees Celsius (-290.2 Fahrenheit), the weather on the moon is driven by a methane cycle rather than a water cycle, causing analogous atmospheric phenomena between the two planetary bodies. While Earth's ocean absorbs carbon dioxide from the atmosphere, for instance, the frigid temperatures on Titan means that bodies of water on the moon absorb nitrogen. But in the case of Titan, the re-release of nitrogen back into the atmosphere happens to be a bit more bubbly than the release of ocean-based CO2 on Earth.

"In effect, it's as though the lakes of Titan breathe nitrogen," Dr. Malaska said in the statement. "As they cool, they can absorb more of the gas, 'inhaling.' And as they warm, the liquid's capacity is reduced, so they 'exhale.'"

Of course, this does not definitively solve the mystery of these magic islands; other hypotheses put forward for the phenomenon include waves, or even solids lurking just below the surface. But the researchers think that Titan's "exhaling" is certainly a viable possible explanation for the phenomenon.

"Thanks to this work on nitrogen's solubility, we're now confident that bubbles could indeed form in the seas, and in fact may be more abundant than we'd expected," said Jason Hofgartner, study coauthor, in the statement.

During the study, the JPL team relied on data from the Cassini orbiter, which has been gathering data since July 2004. Since its launch in 1997, the probe has revolutionized humanity's understanding of Saturn and its moons; but on April 22, Cassini will make its final close flyby of Titan, gathering radar data on the moon's surface. Then, on September 15, the probe will take its final plunge into Saturn's atmosphere, ending its historic 20-year mission.