How the Cassini mission led a 'paradigm shift' in search for alien life

The hunt for habitable (and already inhabited) worlds has largely focused on a “Goldilocks zone” around a star, where it’s neither too hot nor too cold for liquid water to exist. But astrobiologists have begun to broaden their search – thanks to discoveries by NASA’s Cassini orbiter.

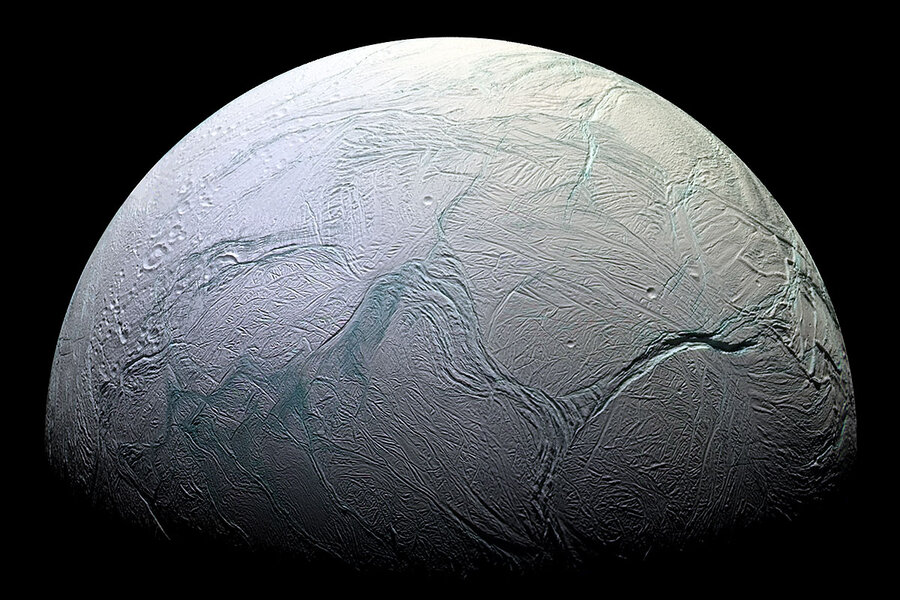

Saturn sits too far from the sun for its rays to melt ice, and yet Cassini discovered that one of the planet’s moons, Enceladus, has a vast ocean sloshing beneath its icy crust. Instead of sunlight, tidal forces keep Enceladus’s ocean warm. The gravity of Saturn pulls at Enceladus’s core, driving thermal processes that create a new Goldilocks zone inside the moon itself.

“It’s definitely been a paradigm shift in where you might find life,” says Cassini project scientist Linda Spilker.

Still, it takes a lot more than water to make a place habitable. But here, too, Enceladus delivers. Icy geysers fueled by Enceladus’s ocean shoot out from cracks in the moon’s surface, allowing the Cassini spacecraft to sample them directly during flybys. What it found is that Enceladus has almost everything required for life as we know it: a source of energy, a source of carbon, and salts and minerals.

Only two ingredients remain missing: phosphorus and sulfur. Cassini lacks the technology to pinpoint their presence or even detect life itself, so these discoveries will be left for future missions.

“Still, you could end up going there and being surprised in a negative way,” says Jonathan Lunine, a Cornell University planetary scientist on the Cassini mission. “Maybe there are things that are required to make life happen that we don’t understand yet.”

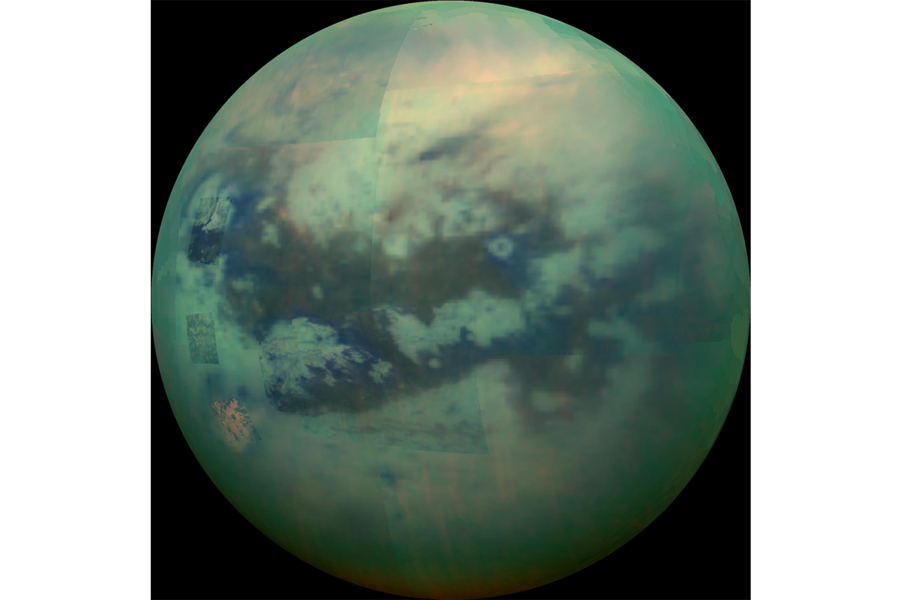

The flip side could also be true, Dr. Lunine says. Life could exist in surprising conditions, like, say, on the surface of Titan, Saturn’s largest moon. Titan bears similarities to Earth. Rain falls to the ground, carving the landscape, filling lakes and rivers, and evaporating back up through a meteorological cycle. But it is methane, not water, flowing through its system.

“We wouldn’t go to Titan to look for Earth-like life,” Lunine says. But that doesn’t mean some exotic form of life couldn’t be swimming through Titan’s methane lakes.

Saturn isn’t the only planet in our solar system with moons that challenge terrestrial-based definitions of habitability. With its own watery geysers, Jupiter’s moon Europa is another exciting ocean world outside the Goldilocks zone, and is the subject of a coming NASA mission, called Europa Clipper, planned to launch in the 2020s.

Whether or not life is found in these subsurface ocean worlds, the results will be profound. “If we find life in these ocean worlds, it tells us that if you put the right conditions together, maybe it’s not so hard to get life started,” says Dr. Spilker. “But, if there’s no life, maybe it is hard.”

For an in-depth look at Cassini's 13-year mission to explore Saturn, check out the Monitor cover story, Ringing Success.