To the moon and beyond: Why China is aiming for the stars

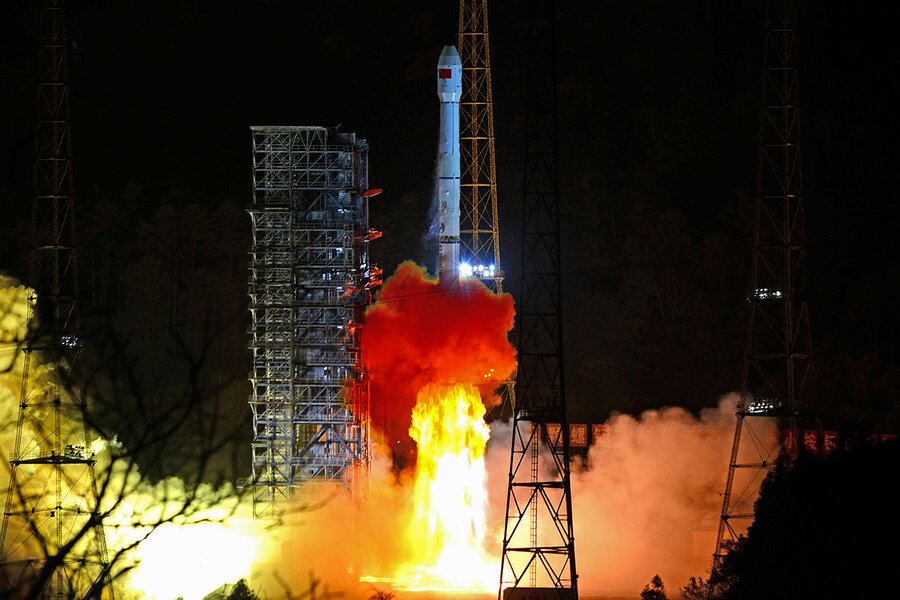

It’s never been done before, even by space-faring nations with decades of experience. But on Thursday, China became the first to land a spacecraft on the far side of the moon.

The Chang’e 4 spacecraft trip is just the latest of China’s space missions. The nation’s burgeoning space program has already sent astronauts into space atop their own rockets, sent several probes to the moon, and has outlined plans for much more.

“China is now a major player in the first rank of space powers, and that’s going to be the reality for decades to come,” says Michael Neufeld, senior curator in the Space History Department at the National Air and Space Museum in Washington.

Why We Wrote This

For Beijing, Thursday's historic lunar landing is as much about cementing global-power status on Earth as it is a foray into the cosmos.

China is just one of several rising players in the global space arena. Gone are the days of the bilateral space race that was once dominated by the United States and the former Soviet Union. Japan has several missions underway, including its second asteroid sample return mission; the European Space Agency has sent robotic probes to Venus, Mars, and a comet; and India has a Mars orbiter.

But China’s path into the cosmos particularly underscores how nations have come to see outer space and space exploration as a frontier vital to their development and ascendance on the global stage.

“China has identified space capability as an element of global leadership,” says John Logsdon, professor emeritus of political science and international affairs at The George Washington University in Washington. “And clearly China wants to be seen as a global great power in influencing the shape of international affairs, and perceives, as the United States and others have perceived, that space capability is essential to military power, to economic power, and to reputation, to prestige.”

China has been somewhat of an outlier in the landscape of space exploration. The competitive space race of decades past has given way to a spirit of international collaboration, with experienced space-faring nations working together with others on missions.

But China has largely had to go it alone. The US, still the dominant player in the global space scene, prohibits its scientists from collaborating with the China National Space Administration (CNSA) on the grounds that sharing space technology could also reveal insights into US military capabilities.

China, in turn, has seized on space exploration as a venue to display its own technological prowess.

A tricky feat

Being the first to land on the far side of the moon is one such opportunity. It’s a tricky feat.

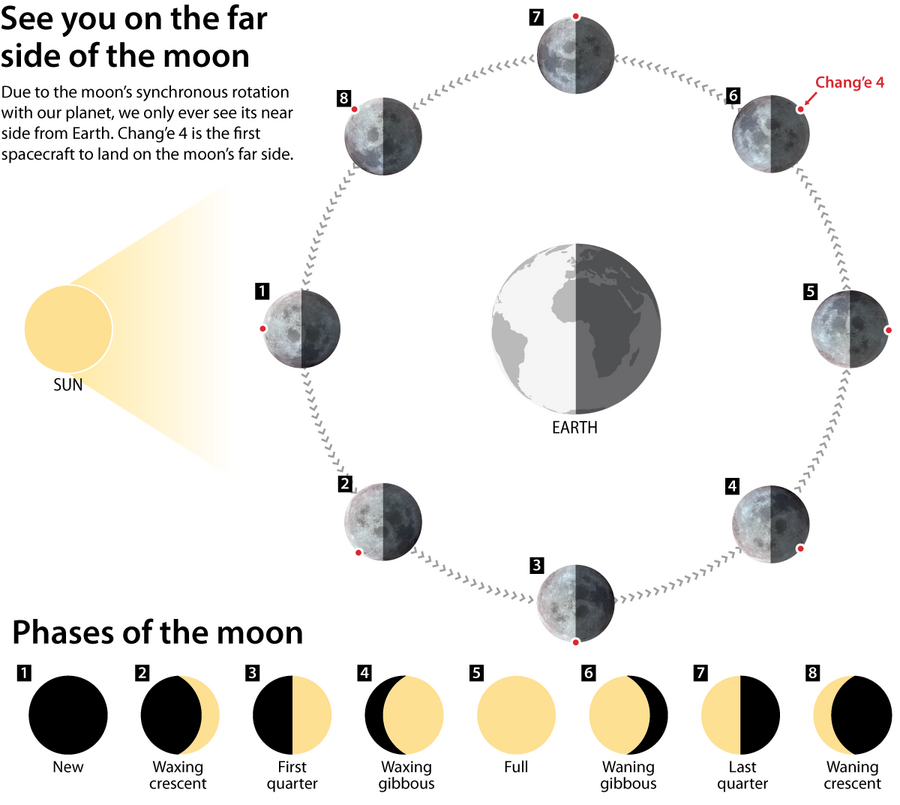

The moon is tidally locked with the Earth, meaning one side always faces toward our planet and one away. As a result, the far side of the moon can’t receive radio signals from the ground. To relay signals to the Chang’e 4 lander, then, China first launched a satellite, called Queqiao.

Although its fourth lunar mission marks a historic first, China’s space agency doesn’t usually target splashy goals.

“This is the first time, really, that they’ve struck out to do something very different and very new,” says Brian Harvey, author of “China in Space: The Great Leap Forward.” “There’s not a mad rush of missions or anything like that. They’re gradually building up a lot of expertise, a lot of knowledge so that they’re in a very strong position” to achieve ambitious goals in the future.

China’s lunar program, Mr. Harvey says, has methodically ticked off the sequence of achievements set out by the US and the USSR during the original space race. The first two Chang’e (pronounced “Chong-guh”) missions mapped the moon from aloft, and Chang’e 3 landed a rover on the near side of the moon. Landing on the far side of the moon was part of the USSR’s plan, too, but the Soviet Union never achieved that, and the US didn’t make it a priority.

The CNSA has ambitious plans for human spaceflight, too. Unwelcome on the International Space Station, due to the US ban, Chinese astronauts aim to establish their own permanent space station by 2020. Already China has launched 11 astronauts into space for increasing amounts of time and technical feats. The nation has also launched two space labs to conduct research and test technologies. A crewed lunar landing could also be on the horizon.

Bold visions

Beyond displaying technological prowess, China is likely using its space program to cast itself as an active participant in the global quest to expand scientific understanding. As a nation facing criticism on the ground for its military posturing and approach to global commerce, China may be seizing on an opportunity to show a positive face to the world, says Andrew Jones, a journalist at the GB Times who covers the Chinese space program.

“What they’re able to do sometimes with the space stuff is present themselves as an outward-looking, sort of looking-to-the-future nation, which is open and looking to contribute to human progress,” he says.

In that spirit of openness, China has invited other nations to send science experiments to be conducted on board its planned space station. For the Chang’e 4 mission, China is working with scientists from Germany, Sweden, the Netherlands, and Saudi Arabia.

This is another way that China is asserting itself as a leader on the global stage, says Dr. Logsdon, particularly as their human spaceflight program takes off. Currently, Russia is the only other nation flying humans into space, although the US is working toward resuming human spaceflight on American rockets. China is also already flying satellite payloads into Earth orbit for other nations.

This is both strategic and economic, Logsdon says. Space has increasingly been seen as rife with economic potential, and charging other nations for rides into space positions a nation well as a global power.

China is also toying with the idea of establishing a crewed lunar base as a gateway to interplanetary human spaceflight. They’re not the only space agency considering this possibility, but such a move would position China to be a major player in the next big phase of space exploration.

So could China emerging as a leader in space exploration shift global priorities in space?

“It’s hard for me to see the point at which the Chinese participation is going to change everything,” Dr. Neufeld says, partially because the Chinese space program is not highly visible internationally, and partially because the space world is already multinational.

But, he says, “it’s adding to human space capability.” Having more space-faring nations means more money to support these expensive endeavors, more engineers to improve technology, and more possible mission targets.